George Pitcher on the latest recommendations for the future of journalism from The Cairncross Review and Knight Foundation.

Dame Frances Cairncross’s review of the UK media, subtitled A Sustainable Future for Journalism, commissioned by Government and published this week, adds to the growing canon of work on both sides of the Atlantic about what should be done about the revolution or crisis – depending on where you work – in the industries of news provision.

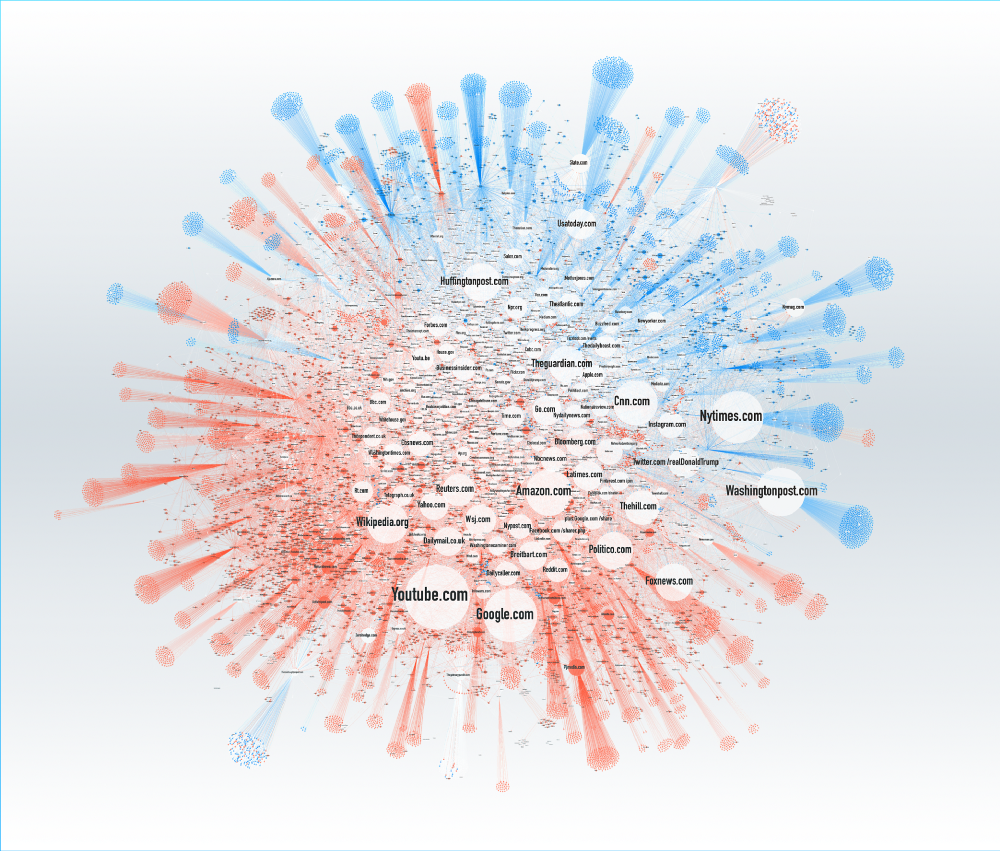

Like those who have gone before her, Cairncross, a former Guardian and Economist journalist, believes that journalism and, by extension, society would benefit from greater monitoring and regulation of social-media behemoths such as Google and Facebook. Her call for tighter regulation here echoes the LSE’s own Truth, Trust and Technology Commission report Tackling the Information Crisis, which recommended an Independent Platform Agency for that purpose.

That a Government-sponsored, though independent, review should now add its weight to the push for social-media regulation is commendable and would seem to make the proposal irresistible. The something in “something must be done” is at least now clear.

It’s in other areas of her report that Cairncross is intriguingly original. She has a learned panel of advisers behind her, has consulted a wide range of the industries and conducted interviews across the UK, US and Brussels, but makes it clear that “the views expressed are ultimately my own”.

That’s a revealing confession. Phrases in the report such as “high quality journalism” and “public interest news” are defined, but still remain vague in their application. She admits that quality is “a subjective concept”, but then adds that “you know it when you see it”. So this is about personal style? If so, it might be taken to sound a little snobbish. It might, in any event, reveal a tendency towards what the Americans would call “motherhood and apple pie”.

This is not simply to have a pop at the establishment figure who is Dame Frances, but to point to a characteristic of the review which might undermine its own aspiration to improve the quality of journalism: It has a very top-down feel to it and it might be argued that the way to improve and maintain journalistic standards is rather more from the bottom upwards. In other words, it is not for Government-appointed figures to judge and approve journalism, but for journalists themselves to do so.

Among the Cairncross recommendations is the support through direct Treasury subsidy of public-interest news, overseen by a new Government-sponsored institute, particularly to fund the reporting of local democracy. This is partly to address the economic crisis in local newspapers and news outlets, which is admirable as an aspiration but worrying as a policy.

State-funded local journalism sounds a bit like nationalisation of the press by stealth and is the thin end of a very big Government-interference wedge. It would doubtless win the approval of press-control campaigners such as Hacked Off, but would and very probably should be resisted by the very journalists that the proposal seeks to support.

In any event, state-sponsored journalism raises too much practical instability for this review’s stated aspiration for a “sustainable future”. What if a change of Government decided such subsidies were an easy first cost-cut? Better by far for Government to restrict itself with controlling aspects of state provision that already adversely affect local media. Cairncross is quite right in this regard to call for further review of the BBC’s provision of local news online, which has contributed significantly to the decimation of local press and which can hardly be the remit of a public-service broadcaster.

A bottom-up approach

By contrast to Cairncross, the Knight Foundation in the US published a report earlier this month titled Crisis in Democracy: Renewing Trust in America, which takes an altogether more bottom-upwards approach to local journalism. It calls for journalists to “practice radical transparency” by developing “industry-wide, voluntary standards on how to disclose the ways they collect, report and disseminate the news.” Rather than Government funding, it looks to “new models for funding for-profit journalism”, with particular reference to models of philanthropy to “increase its support for journalism in the public interest”. Again, a proper use of Government power in promoting local democracy might be found in tax-breaks for investment in local media.

The report calls for more imaginative use of technology in combating disinformation and for greater diversity in newsroom recruitment. It argues that managers should be empowered “to make technology work for them”, by developing “ways to measure healthy dialogue online. These include creating metrics to help analyse balanced, democratic discourse.”

Above all, the Knight Foundation sees local media in the context of good citizenship, rather than public finance, and to this end calls for them to “reach across political divides”, recommending “that communities develop programs hosted by trusted local institutions to convene dialogue among citizens. These exchanges should address important questions ranging from local issues to relevant constitutional questions.” It even goes so far as to suggest a year of voluntary national service for college leavers, to include “engaging in public service journalism, particularly at the local level.”

Much of this doesn’t travel well across the Atlantic to the UK. And it is, admittedly, from the very heart and home of motherhood and apple pie. But it points in a better direction than pouring good public money into a bad and busted local-media business model.

A way forward for local media

For sure, local UK media, with the BBC on their backs, need to find more compelling technological models for distribution of news. But they also need to ask themselves what type of information local people now want, rather than serving up the same old fare. And that is an act of citizenship, rather than an over-simplistic economic solution.

Local journalism needs to re-discover its own mission for itself. It may even need to re-invent itself. Rather than just reporting local crime, for instance, it needs to use its fresh access to big data to show what crime looks like in the area it serves, contextualised in the national picture. And it can liberate rather than constrict a new generation of local journalists by automating the base-load of the local grunt work – what does the working model look like if you automate court reporting, for example?

The common ground of both these reports, Cairncross and Knight, is that local media serve local democracy. They then depart company on how it is to be supported and encouraged, the former looking to public finance, the latter to philanthropy and citizenship. On balance, we need to find ways in which local journalism can re-discover its old craft and creativity for its own ends.

George Pitcher advises Dow Jones, publisher of the Wall Street Journal, on ethics and the future of journalism and is a Visiting Fellow at LSE. He formerly held senior editorial positions at The Observer and the Daily Telegraph. @GeorgePitcher

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of Polis, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science