Students due to finish A-levels in 2022/23 had their GCSE exams cancelled and have suffered COVID-related disruption spread across the last three academic years. Peter Finn, Radu Cinpoes, and Emily Hill offer an overview of changes made to A-Levels since the start of the pandemic and discuss some of the key challenges that lie ahead for UK Higher Education.

In early September 2021, 272,500 (37.9%) of all 18-year-olds in the UK were due to begin a university course. Across the HE sector, upwards of 250,000 students, many of whom will have studied A-Levels, are likely to begin university courses in September 2022. They will do so having had the last three academic years of their education disrupted.

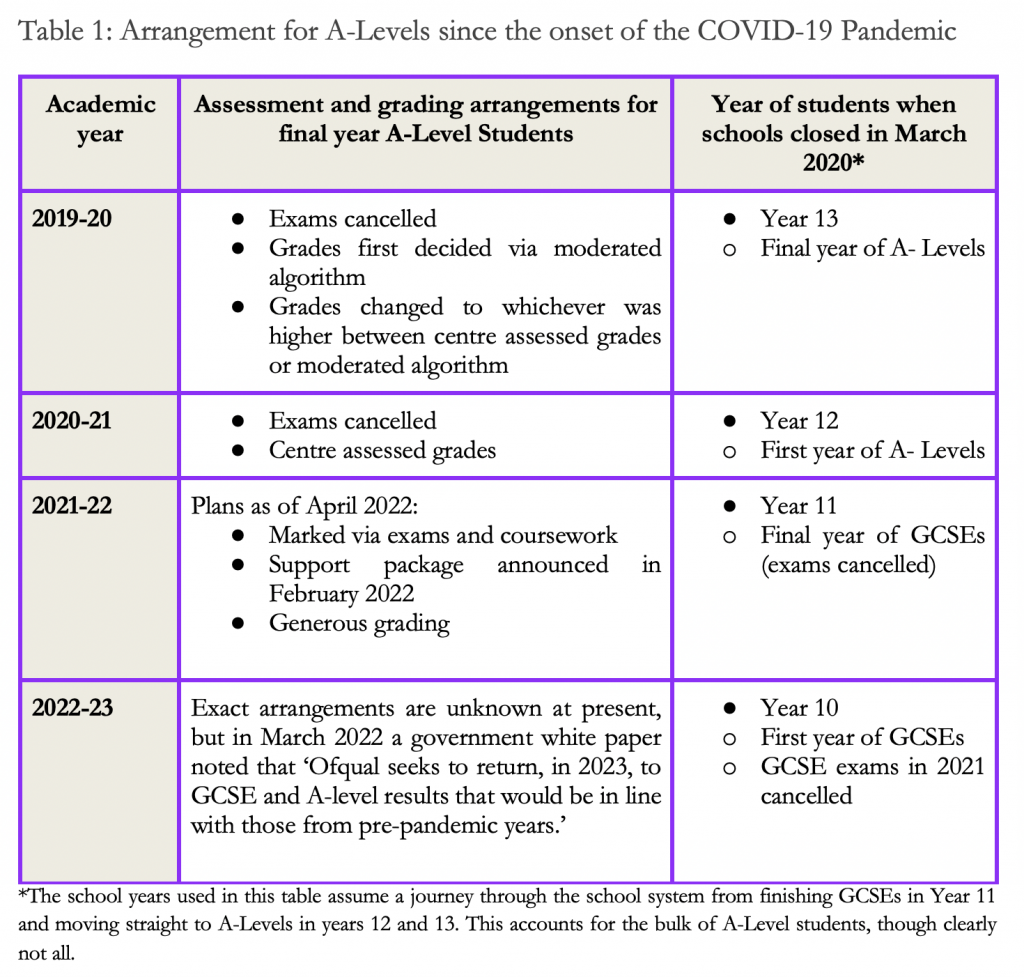

Pressures have included restrictions and lockdowns, loss of learning time and curtailments of academic support, mental health and wellbeing impacts, tech poverty and food poverty. In many cases, these issues pre-dated COVID-19, but they have been exacerbated by it, including through uncertainty around exams, grade controversies, and a related inequality of grade inflation. The assessment arrangements for those finishing A-Levels since the start of the pandemic, as well as the point at which students were at in their educational journey when the pandemic began, are documented in Table 1 below.

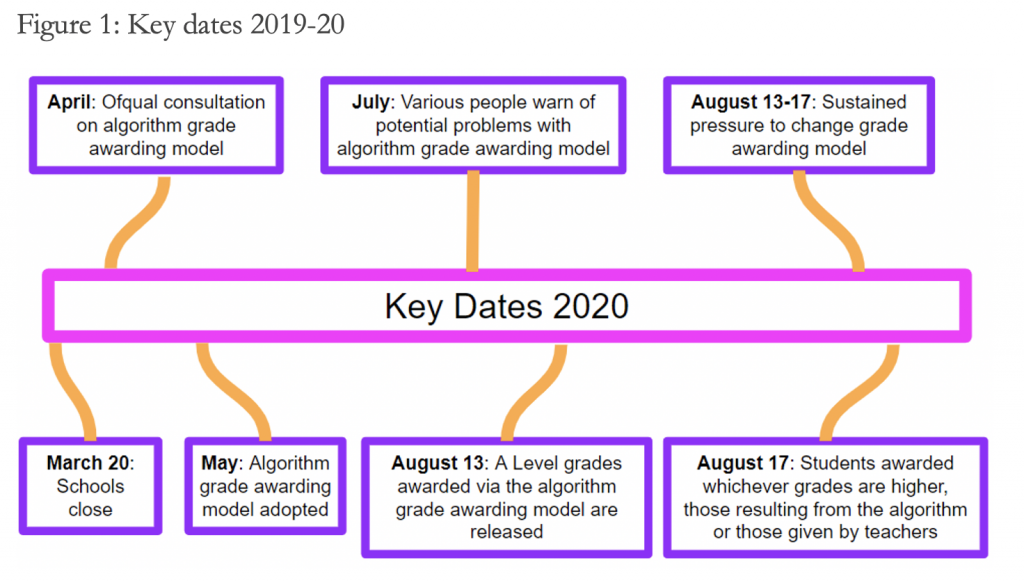

2019-20

For students due to finish A-Levels in summer 2020, and with exams cancelled and teaching halted, in April 2020 the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) held a consultation on proposed guidelines for awarding grades via the use of an algorithm that would moderate grades awarded by teachers, known as teacher assessed grades (TAGs). This algorithm was designed to quell teacher bias and grade inflation, with historic school-level data used to help determine individual grades. Put simply, TAGs were ‘put through a process of standardisation‘. However, this system caused controversy when A-Level results were released on August 13 2020.

This controversy arose as the algorithm appeared to disadvantage students studying in more deprived areas, resulting in high-achieving students from historically low-achieving institutions being downgraded, and lower-achieving students from high-achieving institutions having their grades inflated. Under considerable public pressure, on August 17 the then-Education Secretary Gavin Williams announced a U-turn and pupils were awarded whichever was the higher: the TAG or the moderated grade. Yet, issues with the algorithm grade-awarding model were predicted and Williams was warned about potential negative impacts on individual grades, including by Sir Jon Coles, previously Director-General for Standards for the Board of the Department for Education, and the House of Commons Education Committee.

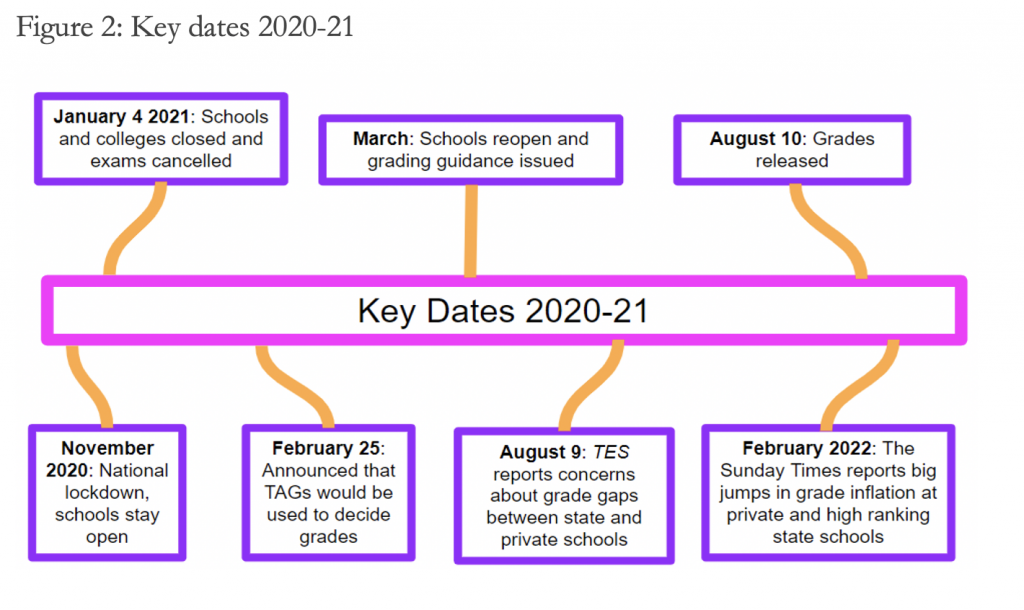

2020-21

Rather than a hoped-for return to normal, the 2020-21 academic year saw continued uncertainty. Though face-to-face teaching returned in September, students had to wear masks in class, and there was broader uncertainty arising from a lockdown in November 2020 (though schools and colleges remained open), and the last-minute closure of schools and colleges for face-to-face teaching on January 4.

After the issues with moderated algorithm grades in 2020, and the cancellation of exams, it was announced on February 25 that, following a consultation between the DFE and Ofqual, final A-Level grades for 2020-21 would be awarded via TAGs. According to Williams, ‘schools, colleges and other educational settings will conduct multiple checks – such as checking consistency of judgements across teachers and that the correct processes were followed – to ensure as much fairness as possible.’ Summarising what this meant logistically, the TES reported that ‘school leaders coped with a number of weighty decisions that would usually be dealt with by exam boards.’

Much-discussed in spring and summer 2021 was grade inflation, with attainment gaps also a concern. Ian Bauckham of Ofqual, for instance, noted concern that the approach adopted could feed into grade inflation and the TES reported just prior to the release of A-Level results that it had been ‘told by sources close to the government that there are concerns about a widening gap in teacher assessed grades in state and private schools’ grades at A level’.

Results from the 2020-21 academic year continued a trend of grade inflation, with 44.8% of students getting an A* or A grades in 2021, compared with 38.5% in 2020. This compares with 25.2% in 2019 and 26.2% in 2018. Yet, the trend of grade inflation played out in a more nuanced manner than grades rising evenly across the board, with private schools showing the biggest jumps in grades, and the largest jump in state schools being likewise weighted towards grammar and selective schools. Reporting by The Sunday Times demonstrated, for instance, that whereas in 2019 16.1% of A-Levels were graded A* at private schools, in 2021 this was 39.5%. Interestingly, there was a 21.3% difference between the biggest jump in private schools and the biggest two-year increase between 2019 and 2021 in state schools. The largest state school increase was at Tiffin School in Kingston Upon Thames, which saw a 35.1% increase in the awarding of A* grades from 32% in 2019 to 67.1% in 2021. Similarly, The King David High School in Manchester saw a 32.5% jump in the awarding of A* from 2019 18.2% in 2019 to 50.6% in 2021. These increases compared with a 11.3% jump overall in the increase of the awarding of A* grades from 7.8% in 2019 to 19.1% in 2021. As such, though the awarding of the highest grades rose overall, this rise was heavily skewed in favour of private, grammar, and selective schools. Essentially, a short-term inequality of grade inflation occurring during the pandemic has tracked longer-term societal stratification and inequality.

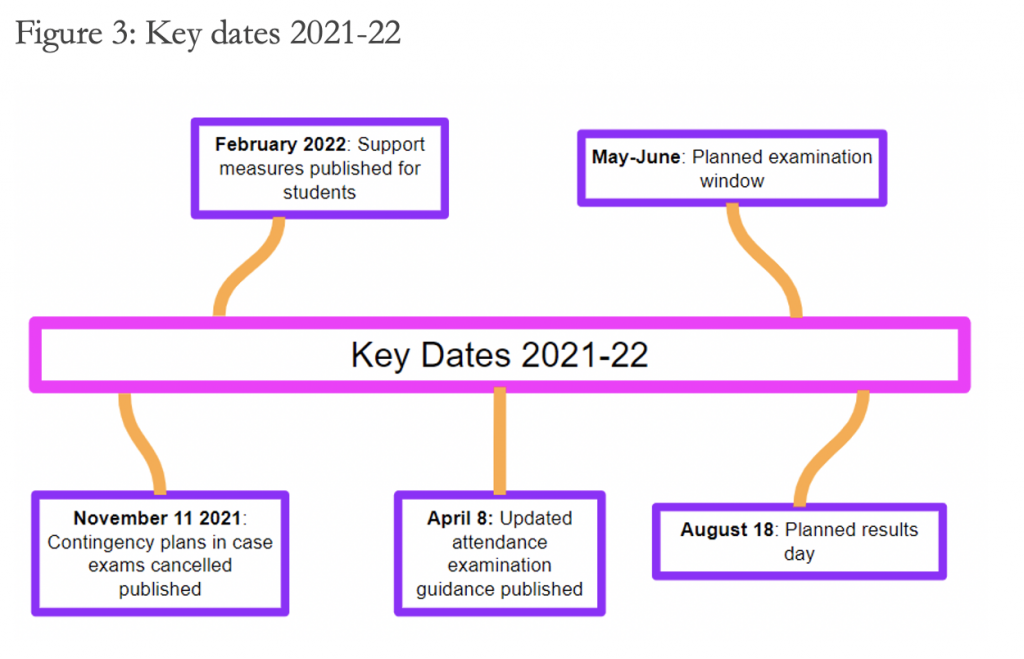

2021-22

The bulk of students finishing A-Levels this year have had their whole time studying A-Levels and the final year of their GCSEs impacted by COVID-19. As with A-Levels in 2020, GCSE exams were cancelled following school closures in March, whilst teaching was disrupted again in the 2020-21 academic year when schools were closed from January to March. On top of this, there have been, among other pandemic-related protocols, off and on mask wearing policies and testing requirements.

At present, it is planned for exams to occur, though contingency plans were also announced. On 7 February 2022, Ofqual announced a range of support measures for GCSE and A-Level students in England. These oscillate around five themes: changes to coursework, optional content, support materials, advance information, and generous grading. These measures reflect similar support on offer in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

UK Higher Education in 2022-23

Academic support

The bulk of students finishing their A-Levels in 2022 have had their education disrupted since the latter stages of their GCSEs. Though they are sitting exams this summer, their GCSE exams were cancelled in 2020, whilst many have missed months of face-to-face teaching due to school closures in 2020 and 2021. Moreover, significant staff and student absences have continued to disrupt learning into spring 2022, with the grading applied this year more generous than pre-pandemic levels.

As such, students entering a HE environment in the 2022-23 academic year who are coming straight from their A-Levels have had significant impacts on the logistics of their teaching and assessment across the previous three academic years. Moreover, official figures show that the support arising from extra pandemic-related provision has been provided unevenly: some students have had greater access to resources to lessen the impact of lockdown than others.

Institutions, teams, and individuals involved in the provision of university services and teaching should be mindful of the need to provide more in-depth support than normal for first-year and foundation students in the 2022-23 academic year, as well as maintaining an awareness of the differences in provision and support that students may have received since March 2020.

Mental health

Mental health impacts have been considerable across all groups during the pandemic. As documented by the charity Mind, young people reflect this broader picture, with a desire for information related to mental health present. Providing adequate support for the sizeable chunk of young people who will enter HE institutions in 2022 is going to be resource-intensive for institutions, with many students also dealing with the pressures of living away from home for the first time. Those involved in pastoral care and mental health support services within higher education should reflect on how they can best support students, whilst other HE staff should maintain an awareness of relevant support services they can direct students struggling with their well-being to.

Inequality

Fostering equality, diversity, and inclusion is a stated goal of universities across the UK. As seen above, there has been an inequality of A-Level grade inflation during the pandemic, seen particularly starkly in the 2020-21 academic year. It is too early to know if this will continue this summer. Yet, given that inequality and its impact on educational attainment is a long-term national trend rather than a pandemic related aberration, even if some ground is clawed back from previous years in 2021-22 it is all but inconceivable that there will be a level-playing field for those taking A-Levels this summer.

Those working at all levels within the HE sector should be aware of the exacerbation of inequality during the pandemic and the need to work towards policies aimed at fostering equality, diversity, and inclusion. In particular, those with the ability to resource support to this end should think about how such resources can be best targeted. There is no one-size-fits-all model, with each institution having a slightly different intake. However, if institutions do not reflect on how best to help mitigate the impacts of inequality exacerbated by the pandemic, attainment gaps may widen further.

Conclusions

The success of the measures put in place for A-Level students this year remains to be seen. However, speaking to the broader education picture as it has evolved since March 2020 David Laws, Executive Chairman of the Education Policy Institute, noted that ‘[w]hat we see is that the north and the Midlands are doing worse than the south and disadvantaged pupils are doing worse than non-disadvantaged pupils, but very notably all pupils in more disadvantaged areas have a high likelihood of suffering severe learning loss. It is not only poor children; it is [also] non-poor children in disadvantaged areas.’ Likewise, the House of Commons Education Committee highlighted in March 2022 that ‘it is clear that school closures have had a disastrous impact on children’s academic progress, with disadvantaged children and those living in disadvantaged areas the worse hit.’ Finally, official figures show that between 2017 and July 2020 there was a rise in the number of children ‘having a probable mental [health] disorder’ from one in nine to one in six.

It is the stated aim of current Education Secretary Nadhim Zahawi and Ofqual to return to normal in terms of examinations and marking during the forthcoming 2022-23 academic year. Yet, as shown in Table 1, students due to finish A-levels next year had their GCSE exams cancelled and have now suffered more than two years of disruption spread across the last three academic years. Moreover, when one factors in the issues raised by Laws and the House of Commons Education Committee, the impact of a rise in mental ill health, and long standing inequalities, it is likely that whilst 2022-23 may logistically look more like pre-pandemic years, the current balance of evidence suggests that educators and policymakers will be dealing with issues related to inequality in A-Levels and other FE qualifications moving forward.

______________________

Peter Finn is Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University, London. He is the Principal Investigator on The Covid-19 and Democracy Project.

Radu Cinpoes is Head of Politics at Kingston University. He is Co-Investigator for The Covid-19 and Democracy Project.

Emily Hill is a final-year Human Rights and Social Justice BA student within the Politics Department at Kingston University London, and was a Research Assistant with The Covid-19 and Democracy Project.

Photo by Siora Photography on Unsplash.