Simon Bastow examines some of the background and issues relating to ‘notional’ seat allocations as a result of 2007 constituency boundary changes in England and Wales.

Simon Bastow examines some of the background and issues relating to ‘notional’ seat allocations as a result of 2007 constituency boundary changes in England and Wales.

As the election campaign moves towards its crucial last seven days, quite probably the last thing on the vast majority of minds is the issue of electoral constituency boundary change. So much so that one might be easily forgiven for reading this first sentence, agreeing, and then going and reading something much better instead.

For those, however, who have been exposed to the constant references to seat projections based on ‘notional’ 2005 general election results, widespread across the BBC and other media broadcasters in recent weeks, the issue deserves at least some probing. If nothing else, to satisfy that there isn’t a story there, and that debates about British electoral boundary changes are low-profile for very good reason.

Anyone hunting for latent signs of gerrymandering will find little evidence of it. Seminal research by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher (2007) found that boundary changes under the Labour government would in fact ‘notionally’ benefit the Tories (plus 12 seats) more than Labour (minus 7 seats). And Martin Baxter’s Electoral Calculus shows a broadly similar estimate of marginal Tory gain from the new arrangements.

Interestingly, whereas Rallings and Thrasher predict no change in the Liberal Democrat seat share, Electoral Calculus boosts the Liberal Democrat seat share by 5. (There was a time when this would have been cause enough for excitement at Lib Dem HQ – but Cleggspectations are now much higher)

At the centre of this issue has been the need to establish a baseline against which poll predictions and seat outcomes could be assessed, in light of Boundary Commissions changes to electoral constituencies in England and Wales in June 2007. Although net outcomes of this process seem low key, net change conceals considerable movement in constituencies and wards.

Table 1: Constituency changes since the 2005 general election

| England | Wales | Scotland and Northern Ireland | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No change in constituency | 55 | 18 | 77 | 150 |

| Existing constituency changed | 401 | 19 | 420 | |

| Totally new constituency | 77 | 3 | 80 | |

| TOTAL | 533 | 40 | 77 | 650 |

| (Constituencies disbanded) | (73) | (3) | (76) |

One need hardly look further to find a clearer example of how social science research has had a direct impact on society and media. Not only was Rallings and Thrasher’s work central to the actual decisions taken by the Boundary Commissions up to 2007. But this work was also done in cooperation with the BBC, Sky, and other broadcasters, with a view to establishing a common baseline from which the media could drive the ongoing projections industry and analysis.

In dealing with the frankly ludricrous limitation that ward-level data is not and has never been collected for general elections (althought it is collected for local elections), Rallings and Thrasher used local election data at ward level to model likely voting behaviour at general election level.

Using this data, we can assess the level of ‘disorientation’ resulting from voters being moved from one constituency to another, where constituencies have different electoral profiles and are led by MPs from different political parties. I.e. the extent to which boundary changes (and not elections) result in electors being moved from Constituency X led by an MP from Party A to Constituency Y led by an MP from Party B.

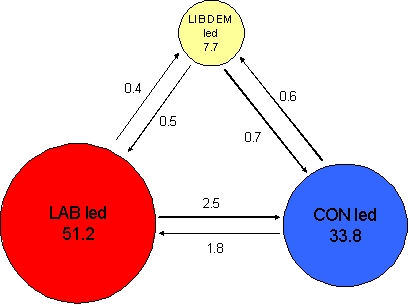

Figure 1: Percentage of the electorate in England and Wales transferred between constituencies held by different parties as a result of 2007 boundary changes

Source: Analysis of Rawlings and Thrasher ‘notional data’ for 2005 election results under new boundary arrangements

Figure 1 shows the transfers of electorate in England and Wales who are affected by boundary changes of some kind or another. (Percentages refer to the total electorate in England and Wales and sum to 100 per cent). For example, 51 per cent of the 2005 electorate were in a Labour constituency prior to the boundary changes, subject to some kind of boundary change, and remained in a Labour-led constituency after the change.

Around 2.5 per cent of the electorate, however, were in Labour-led constituencies prior to the change, but found themselves in a Conservative-led constituency after the change. The arrows in Figure 1 show the direction of change along these lines.

Summing the percentages on the arrows suggests that around 6.5 per cent of the electorate are redesignated ‘notionally’ into constituencies which are held by different parties. This may not seem high, however it is worth pointing out that this is equivalent to around 2.5 million voters who have the potential to be dazed and confused by their new notional status.

And in some constituencies, the disorientating and potential unpredictable effects of boundary changes on the ground cannot be overlooked. For example, in the new seat of Filton and Bradley Stoke in Avon, 46,000 electors came from Labour-led constituencies and 16,500 electors came from Liberal-led constituency, yet the new constituency was ‘notionally’ Conservative. Who can predict how that piece of electoral engineering will turn out?

Several points may be drawn from this brief overview. First, there are obvious dangers in predicting voter preferences at general election from their aggregated voting behaviour at local election level. This is particularly relevant given the increasingly presidential-style personality campaigning which has been evident during the 2010 campaign. Also, notoriously low turnout in local elections may skew any picture of general election preferences if extrapolated too freely. (Martin Baxter’s work has attempted to address the effect of local election turn out in terms of extrapolating to national level).

Second, and perhaps more fundamentally, the need for such heroic extrapolation is only made necessary by the fact that it is still impossible to get hold of data broken down to ward level for UK general elections. Ward data is systematically generated at local election level (hence Rallings and Thrasher’s use of it), however for some reason the system has been able to resist publication of this data in more fine-grained chunks.

Third, we might ask whether these boundary changes will have any significant effect on the outcome of the election. Probably not in any direct or fundamental sense. Having said that, any new ‘disorientating’ effects in isolated areas may feed into the unpredictability which is currently felt vis-à-vis the performance of the Liberal Democrats. New and seemingly random combinations may well occur as a direct result of the constituency changes – the effects of which may lead to unpredictable breakthroughs or ‘new dawns’ in previously partisan constituencies.

Finally, it may be that a shift to a more proportional electoral system in the future will have implications for electoral constituency design. Under the plurality system, one can argue that a degree of chronic stability in constituency design and two party dominance over the years have been largely self-sustaining. Any movement towards three party or even multi-party system of the kind which the coming election promises, may over the long term encourage the decline in the idea of ‘safe seats’, and hence a shift in the way that parties divide their resources, strategies, and efforts across constituencies.

The debate has not ask if we want fewer M.Ps as the population grows , do we ned more M.P.s Because we don’t see them untill election time, out with the people I say

A parochial note from North West London about voter disorientation: residents of Gospel Oak ward have found themselves moved from Glenda Jackson’s Hampstead and Highgate constituency (now Hampstead and Kilburn) into Frank Dobson’s Holborn and St Pancras.

Both are (obviously) held by Labour, but the boundary changes have led to a new 2005 notional Rallings and Thrasher “result” giving Jackson a majority of 474, well within the projected Labour-Lib Dem swing. This has propelled her constituency to number 8 on the Lib Dem’s target list, and sees Ed Fordham shopping for a new suit.

But Gospel Oak voters hoping to participate in this “change” election are likely to miss out, with Dobbo sitting on top of a juicy, notional 2005 majority of over 7000. May you live in interesting times, perhaps, but not necessarily an interesting constituency.