Ralph Scott estimates the change in political values that occurs within individuals who graduate from university by applying longitudinal modelling techniques to data from the 1970 British Cohort Study. He finds that achieving a degree reduces authoritarianism and racial prejudice and that it also increases economic right-wing attitudes.

Ralph Scott estimates the change in political values that occurs within individuals who graduate from university by applying longitudinal modelling techniques to data from the 1970 British Cohort Study. He finds that achieving a degree reduces authoritarianism and racial prejudice and that it also increases economic right-wing attitudes.

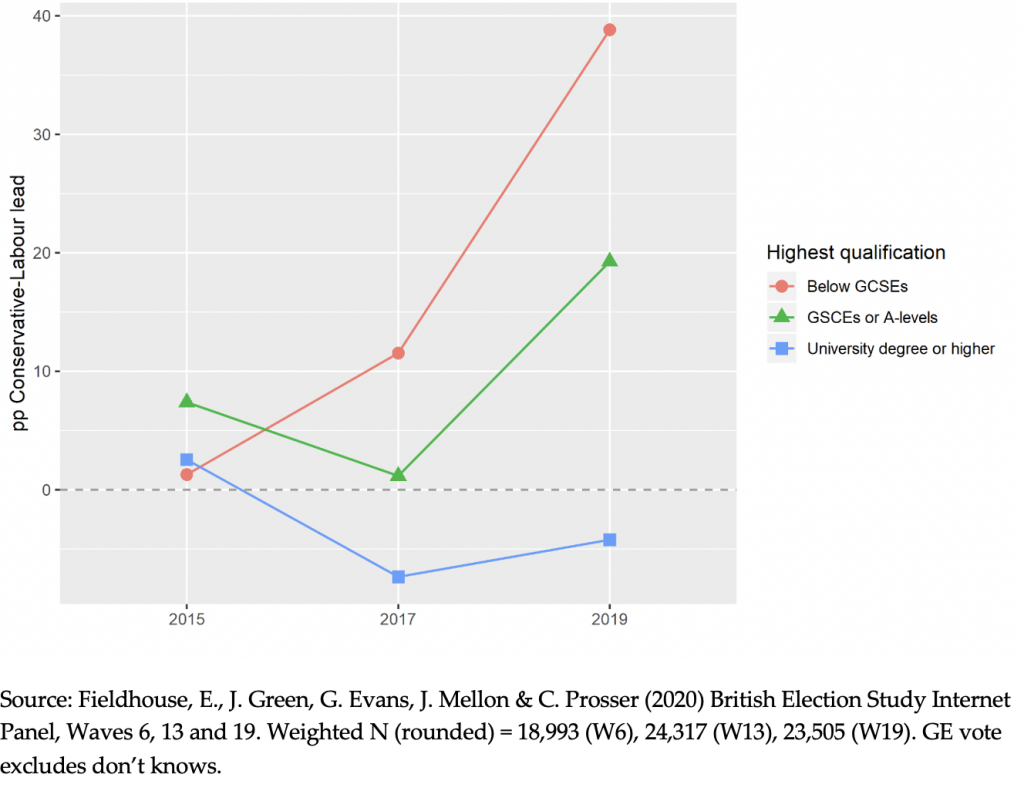

An individual’s level of education is increasingly predictive of their political attitudes and behaviour. In Britain, data from the British Election Study reveals just how stark this relationship has become. Figure 1 below shows the proportion of each educational category voting Conservative, minus the proportion voting Labour, at the 2015, 2017, and 2019 General Elections. As can be seen, among those without school-leaving qualifications such as GCSEs or A-levels, the difference in support between the two parties has moved from approaching parity to almost 40 percentage points.

Figure 1: Conservative lead by level of education, 2015-19.

This educational polarisation is not a phenomenon unique to Britain but is instead present across established democracies, driving the growth of green-liberal parties and an authoritarian-populist backlash, with some suggesting that higher education represents a new political cleavage in Western Europe. So why has education emerged as a major predictor of political behaviour?

One potential explanation is through the effect that education has on political values. These are latent scales capturing an individual’s broad political outlook on economic and social issues, which have been shown to be valid, consistent, and persistent within individuals over time. On average, those with higher levels of education are more economically right-wing and socially liberal and less prejudiced.

So the argument runs that widening participation in higher education has reshaped the overall values structure in Britain, and the electoral shock of Brexit raised the salience of cultural values for vote choice, accelerating a pattern of realignment that had been progressing steadily for some time. Decompositional analysis provides evidence for this, finding that the relationship between education and vote choice in the referendum was almost entirely mediated by its effect on cultural values.

But is it really the case that university is having a causal effect on political values? Couldn’t the difference be explained simply by more liberal young people selecting into higher education? This is the question I investigate in a recent article, finding that in fact, the answer is both.

In the study, I estimate the change in political values that occurs within individuals who graduate from university by applying longitudinal modelling techniques to data from the 1970 British Cohort Study. Specifically, I apply two-way fixed effects (TWFE) and random effects within-between (REWB) models, which account for observed and unobserved time-invariant confounding (and therefore selection effects), as well as the effects of time itself. In addition, the random effects approach allows the individual-level effect of graduating to vary, which overall provides a robust causal estimate (albeit with observational data).

I look at three political values: authoritarianism, understood as support for social order over individual liberty (for example, the death penalty or harsh sentences for criminals); economic Left-Right values, which captures views on inequality and the role of the state in the economy; and racial prejudice, which measures hostility towards racial out-groups. I include the latter given its growing significance for political behaviour in Britain.

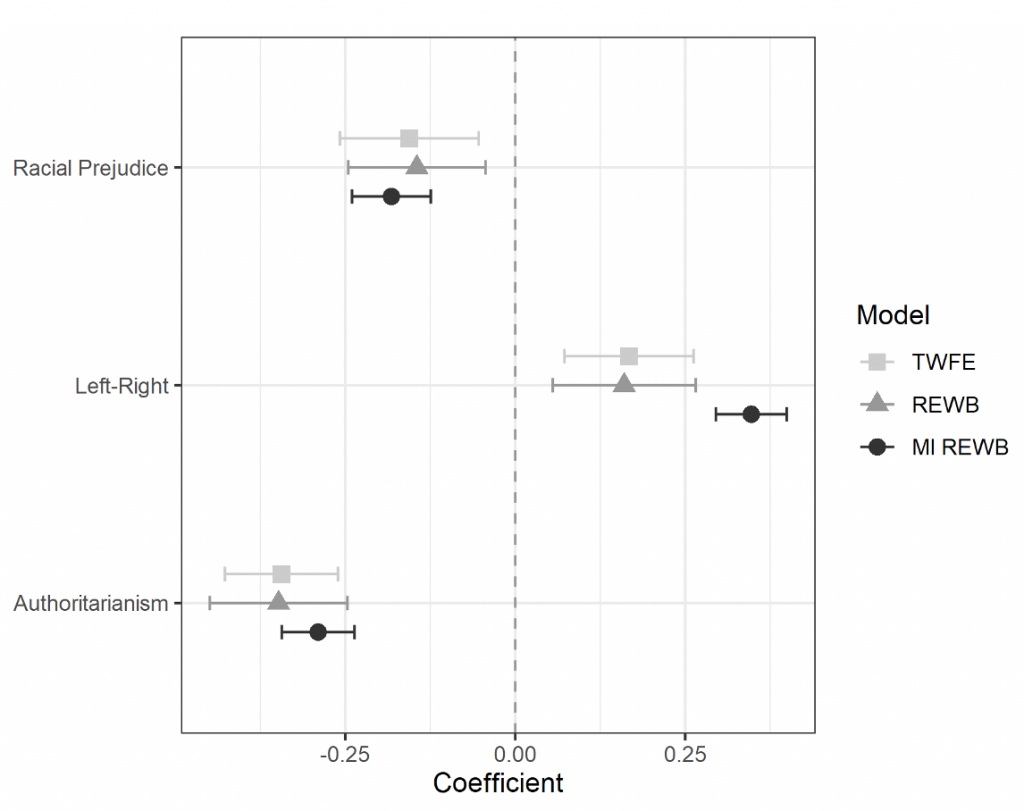

I find that graduates become less authoritarian, less racially prejudiced, and more economically right-wing due to achieving a degree, as shown in Figure 2. Three estimators are employed to give confidence in the results: the TWFE and REWB estimators described above, plus a REWB estimator applied to 75 multiply imputed datasets to account for non-random attrition in the cohort study data.

Here and throughout, a higher value on the outcome indicates higher levels of racial prejudice and authoritarianism, and more economically right-wing values. As the outcomes have been standardised and the treatment is binary, the x axis can be interpreted as an effect size (measured in standard deviations), while the standard errors used to estimate the 95 per cent confidence intervals represented by the error bars take account of the clustering within individuals.

Figure 2: Estimated treatment effects of university attendance on political values (N (TWFE and REWB) = 1520, N (MI REWB) = 15874, M = 75).

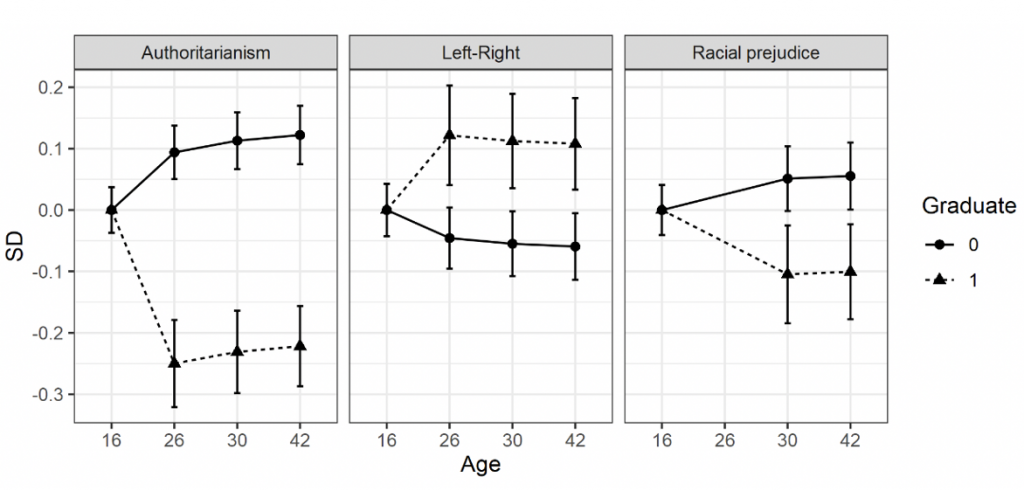

While the overall effect of gaining a degree on these three values is clear, the differing magnitude is perhaps expressed more simply by plotting the estimated values trajectories for graduates and non-graduates over time, as in Figure 3. This displays the estimated marginal means from the TWFE modelling and shows the strength of the effect on authoritarianism relative to the other two outcomes. It also suggests that the effect of university is quick to materialise but then stable, with political values relatively unchanging over the rest of the life course after early adulthood. This lends strength to the idea that higher education plays an important role in political socialisation and values formation.

Figure 3: estimated marginal means of political values for graduates and non-graduates by age (N = 1520).

These findings provide useful insight into why graduates and non-graduates have started behaving differently at the ballot box, suggesting that the partial realignment observed in Britain since the EU referendum may be partly attributable to the values differences from differential higher education participation across the generations. Given the participation rate in higher education continues to grow among under-30s in Britain, we should expect to see continued long-term aggregate value change towards more liberal values, potentially generating further political conflict along the cultural values axis during this transition.

But this research also leaves at least two important questions unaddressed. The first is whether these effects found among those born in 1970 hold for more recent generations of graduates, not least due to changes in the participation level and fees regime since then.

Secondly, we are also left with the question of why university changes values. There are various competing explanations for each set of values within the causal literature on the topic: whether it is the graduate premium leading to higher earnings, and so lower support for redistribution; the impact of peer socialisation in what remain relatively elite institutions; the liberalising influence of faculty and university culture (although evidence for this is more limited); social mixing across difference and the intergroup contact effect; or the effects of increased cognitive sophistication. These remain to be examined more fully in future work: yet with the significance of higher education in politics only growing, such research is necessary to more fully understand its effects.

____________________

Note: The above draws on the author’s published work in Electoral Studies.

Ralph Scott is a Research Associate and doctoral candidate in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Ralph Scott is a Research Associate and doctoral candidate in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash.