Reports of domestic abuse rise after football matches. Ria Ivandic, Tom Kirchmaier and Neus Torres Blas find that binge drinking is the key factor, with alcohol-linked violence against live-in partners happening more often on match days.

Reports of domestic abuse rise after football matches. Ria Ivandic, Tom Kirchmaier and Neus Torres Blas find that binge drinking is the key factor, with alcohol-linked violence against live-in partners happening more often on match days.

The first instances of violence associated with football can be traced back to 14th century England. In 1314, King Edward II banned football in London (the game at the time was played with a pig’s bladder as a ball) due to the disruption it was causing.

Fast forward to modern times and concerns around football hooliganism in England peaked in the 1980s, leading to the Football Spectators Act 1989, which introduced specific football-related offences and the ability to ban individuals from attending matches. The act was strengthened 11 years later after violent clashes during Euro 2000. Since then, the violence around football has reduced and it is now largely considered a thing of the past. But while public and visible violence around stadiums may have lessened, has it moved to the more private sphere of the home?

Ann, a victim of domestic violence, described her experiences: ‘I used to dread the World Cup ‘cos he wasn’t a drinker my husband but could guarantee come the World Cup he’d drink, ‘cos he’d be with all his friends watching it at whoever’s house, mine, in pub, wherever, and that’s where he drinks and he get even nastier when he’s had a drink, not a very nice person.’

Police forces around the world have identified surges in domestic abuse reports following big sporting events in national and international competitions, like the football World Cup. But the existence of a causal link between football and domestic abuse, and the mechanisms through which it runs, have not been comprehensively studied.

We use detailed data to estimate whether football triggers certain people to commit domestic abuse, and consequently, what are the hourly dynamics of violence against intimate partners during and after a game. We also investigate the channels through which perpetrators of domestic abuse are triggered by football — whether through heightened emotional states or increased alcohol consumption.

Our research uses detailed and confidential high-frequency administrative data from the UK’s Greater Manchester police force, combining five datasets on domestic abuse calls and crimes over an eight-year period. These records contain the timing, location, description, type of relationship, information on the victim and the perpetrator, including whether they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

The novelty of these data allows us to investigate the channels through which football affects domestic abuse with great precision. We complement this with data on all matches involving Manchester United and Manchester City in different tournaments held between April 2012 and June 2019 – amounting to almost 800 games – with detailed data on the timing, location, result and pre-game expectations about the result of the game.

Our research design uses an event study to analyse whether there is a statistically significant change in the incidence of domestic abuse during or after football matches. To estimate the effect of the games, we calculate the expected rate of domestic abuse at any one time assuming it would have evolved similarly over time as it did in the past, in the absence of the game.

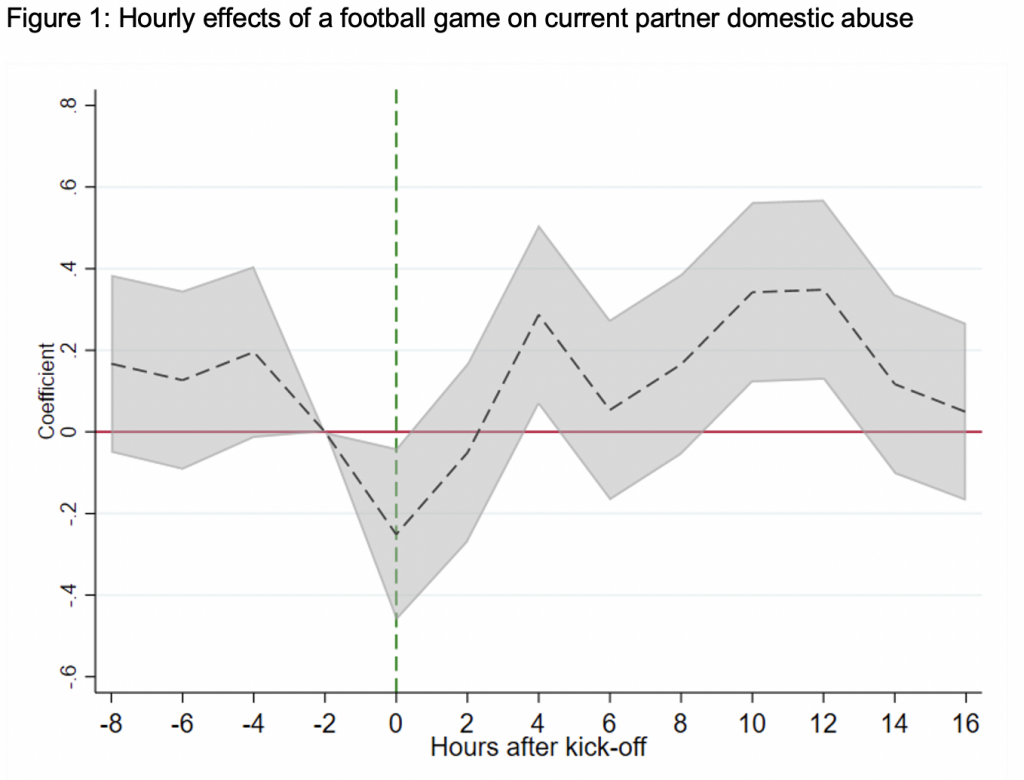

The immediate effect of a football game is a decrease of 5% of domestic abuse incidents (in absolute terms about 0.25 fewer incidents) during the game, compared with two hours before the game. This initial decrease lasts for the two-hour duration of the game, after which domestic abuse levels return to their pre-game state (see Figure 1). This pattern shows that potential perpetrators give their attention to the game during that time.

After the match, domestic abuse incidents start growing by 5% every two hours in the first four hours following the game. The highest increases in magnitude (8.5%) occur 10 to 12 hours after the start of the game and then the effect disappears around 16 hours after the game.

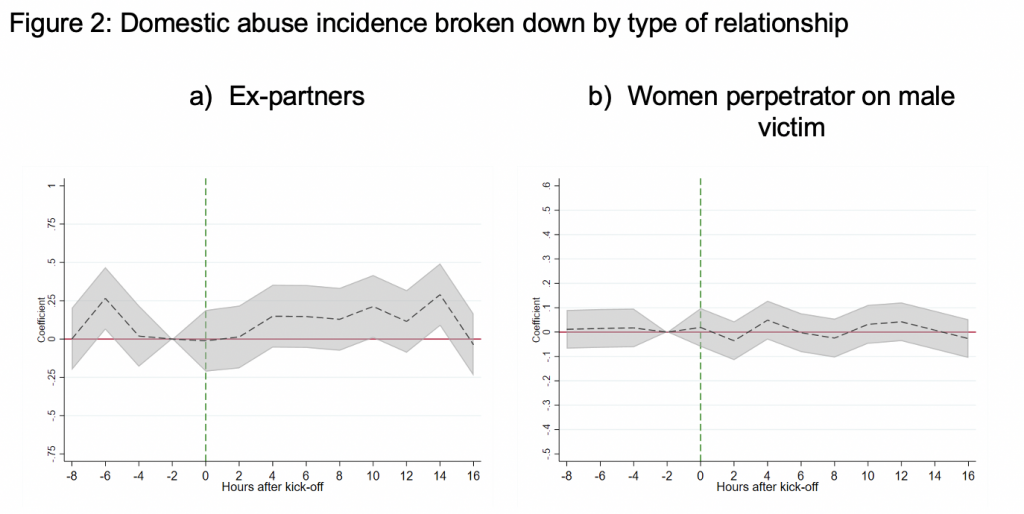

We use the detailed information on the type of relationship, and victim and perpetrator characteristics to understand the conditions under which the rise in abuse occurs. As Figure 2 shows, we find that domestic abuse between ex-partners is not affected by football, nor is that committed by a woman perpetrator. Hence, the changes in domestic abuse are driven by abuse between current partners at home in the aftermath of the game, and is driven exclusively by male perpetrators on female victims.

Understanding why football games lead to domestic abuse can have important implications for public policy actions such as how to organise games or how to design information campaigns. Two main explanations have been put forward by previous research: strong emotional reactions caused by the game; and increased alcohol consumption.

The first argues that the increase in domestic abuse is caused by strong emotional reactions of football fans to the game, which are stronger after unexpected results due to the effect of reference dependence. If increased emotions are the main channel, then increases in domestic abuse should be seen immediately following the game and be stronger for unexpected results. But if alcohol is the main channel, then increases in domestic abuse should occur a few hours after a game and abuse by perpetrators who have not been drinking alcohol should not be affected.

We use detailed data on the pre-game expectations about the result of the game (betting odds from betting agencies) and detailed flags on whether the perpetrator was under the influence of drugs or alcohol to test these hypotheses. We classify a match as an upset loss if the probability of winning assigned by the betting market was higher than 55%, yet the team lost the game; and we classify a match as an upset win if the probability of winning assigned by the betting market was lower than 45%, yet the team went to win the game.

We do not find evidence that upset losses, those likeliest to induce the strongest negative emotional reaction, have any additional effects on domestic abuse incidence with or without alcohol. Moreover, we also do not find any spikes in domestic abuse just after the game, hence our results do not confirm predictions on the importance of heightened emotions in triggering abuse.

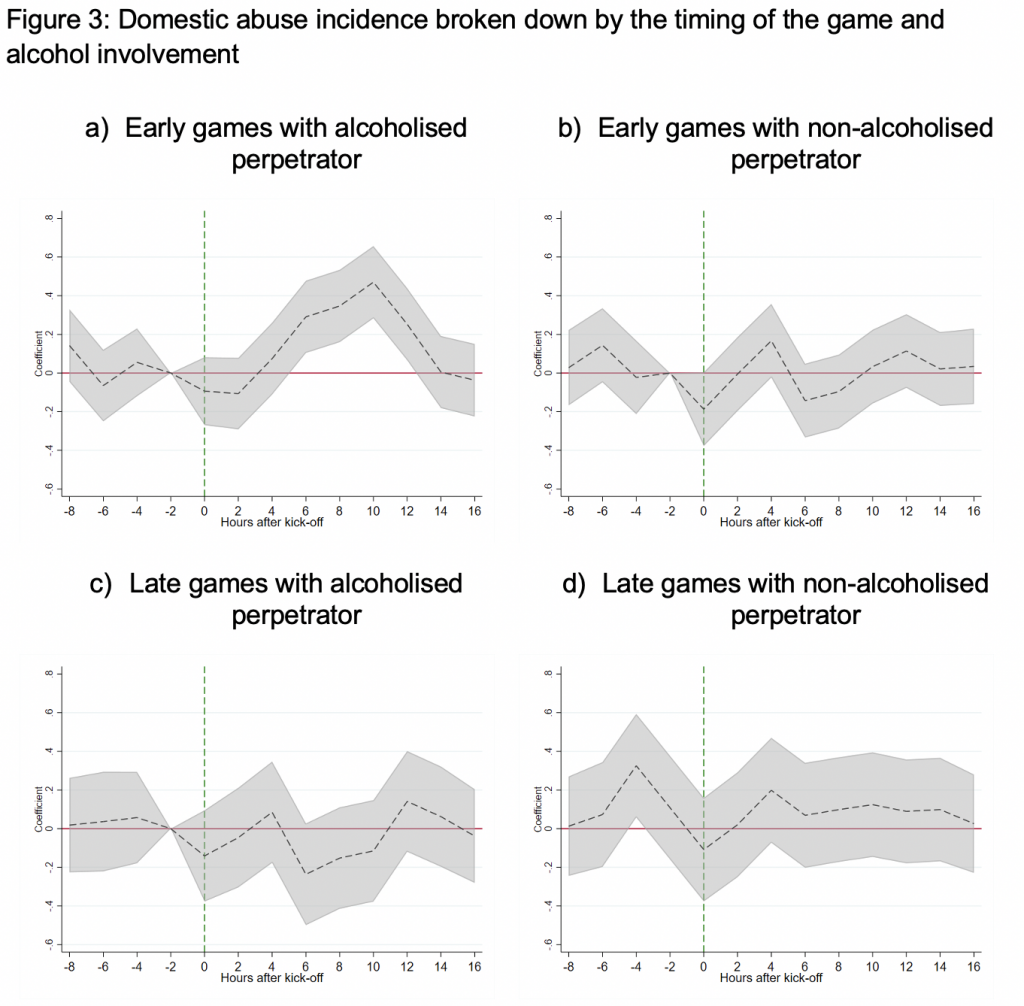

To check whether football games lead to domestic abuse through increased consumption of alcohol, we repeat our analysis looking at domestic abuse reports involving perpetrators who had been drinking alcohol and those who had not been drinking, across early games (starting before 6.30pm) and late games (after 6.30pm). We hypothesise that early games allow a longer time for drinking, as spectators would gather at a pub mid-afternoon before the start of the game and stay until closing time at 11pm.

We observe that following early games, domestic abuse incidents involving perpetrators who have been drinking alcohol start increasing after the first two hours after the match and keep increasing until they reach a maximum 10 hours later. At the peak this equates to 0.5 incidents more than on similar non-match days, 25.3% more than average. The cumulative effect is an increase of 7.6% of all incidents over the 16-hour period. By contrast, we observe no effect when the perpetrator is sober, nor for late games.

Finally, it is important to emphasise that our research does not show that football by itself causes domestic abuse. Football has no effect on domestic abuse dynamics of non-alcoholised perpetrators. Really, it is only through excessive consumption of alcohol that football games trigger certain domestic abuse perpetrators.

This is also an important finding for policy-making as we discuss ways to reduce domestic abuse. Our research shows that a crucial way forward is to focus on policies that would reduce binge drinking, such as, but not limited to, scheduling games later in the day and reducing alcohol advertising associated to football. Moreover, our findings invite more research on whether policies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy for alcohol addicts, could mitigate the relationship between excessive alcoholisation and violent mental states.

___________________

Note: the above first appeared in CentrePiece, the magazine of the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance, and summarises the authors’ CEP discussion paper.

Ria Ivandic is a lecturer in political economy at the University of Oxford and a postdoctoral research economist in CEP’s community wellbeing and labour markets programmes.

Ria Ivandic is a lecturer in political economy at the University of Oxford and a postdoctoral research economist in CEP’s community wellbeing and labour markets programmes.

Tom Kirchmaier is director of the policing and crime research group at CEP.

Tom Kirchmaier is director of the policing and crime research group at CEP.

Neus Torres Blas is a research assistant at CEP.

Neus Torres Blas is a research assistant at CEP.

Photo by Alexandre Brondino on Unsplash.