Social housing is still an important part of the way we live in the UK – more than one in six homes in Britain are owned by local authorities or social landlords. However, the system has been gradually eroded over the past three decades, and we are now at a point where demand for social housing greatly exceeds supply. Chris Gilson investigates what effects David Cameron’s recent initiative to end ‘tenancy-for-life’ might have on social housing and the people that live in it.

At a recent CameronDirect event, David Cameron remarked that the government would explore short-term tenures for social housing tenants, as well as ending the current ‘tenancy for life’ approach to social housing. This apparently radical change comes on top of an erosion of social housing stock over past decades, since the ‘right-to-buy’ scheme was first introduced for council housing tenants in the 1970s. Under Thatcher and then Major, Conservative governments were largely against local authority housing, instead preferring housing associations to run social housing.

Initially, the new Labour government in 1997 was much more in favour of local authority housing, but as the administration progressed ministers increasingly wanted to transfer public sector assets away from the public sector. So Labour also began a more ‘hands-off’ policy encouraging local authorities to transfer their properties to housing associations, as well as encouraging sales under right-to-buy.

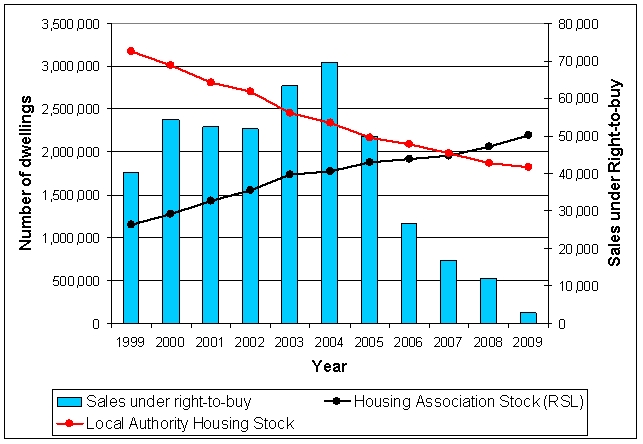

Since 1999, local authority housing stocks have dropped by 1.3 million, and housing association stocks have risen by over 1 million, as the chart below shows. During most of this period, social tenants were able to vote against these transfers (and often did), for fear of increased rents or poorer maintenance regimes.

Social Housing Stock and right-to-buy sales 1999-2009

While right-to-buy sales have declined since 2004, over 440,000 homes have been sold from the social housing system since 1999, while only 2,500 local authority and nearly 223,000 housing association homes were built in the same period. (For comparison, the private sector has constructed 1.4 million homes since 1999).

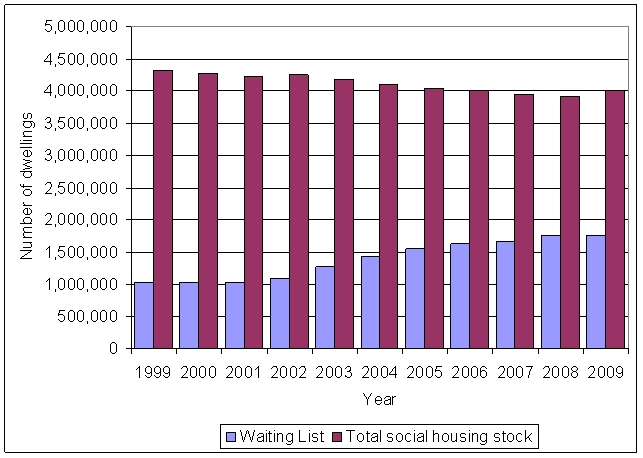

It’s now clear that we are simply not building enough social housing to accommodate demand. In the last decade, the number of households on housing waiting lists has risen from 1 million to 1.8 million (accounting for 4.5 million people), and at the same time the total stock of social housing has fallen by nearly 300,000, as my second chart shows.

The social housing stock and the size of waiting lists, in England 1999-2009

Source: DCLG housing tables

Source: DCLG housing tables

Currently social housing tenants are able to apply to buy their homes after five years, but it is uncertain how this would fit with a five year tenancy lease. When Cameron floated his council tenancy change, is he proposing a phase-out of the ‘right to buy’? – perhaps where existing tenants still have this right, but new ones would have to sign-up to a five or ten year short term lease, with no guarantee of this facility after that. The right to buy scheme encouraged long-term residency in an area, whereas this new policy may do exactly the opposite. At an extreme, one could envision a local authority attempting to ‘export’ its social housing tenants to another part of the country with higher job growth at the end of their tenancies, leaving the household involved little choice but to uproot or face losing their home anyway.

A problem for councils will be the criteria to follow when determining whether tenants should be ‘moved on’ from social housing at the end of their short-term tenure. They will have to walk a very fine line. A relatively ‘lax’ system would offer little change to the present system.

Too harsh a regime, and tenants who have gained new or more highly paid jobs over the course of their tenancy risk losing their council homes and having to move into the more highly priced private rental market. During times of greater prosperity, people moving out to private rented accommodation could be beneficial for social housing landlords (both councils and housing associations) and the tenants themselves. But, while job and wage security is now much more uncertain than in the recent past, gaining employment or a better job may not necessarily mean that tenants will be able to move out of social housing, because there is a reasonable chance that this employment may be ad hoc or transitory. Tenants will rightly fear that if they lose this employment, then maintaining a privately rented home would be much more difficult than their original social accommodation.

So as Cameron proposes it, the scheme could well act as a potential additional disincentive for people to get a job, a perverse outcome to a policy aimed at getting people out of social housing. In an economic downturn, gaining employment is only likely to get harder, adding to an existing problem; employment levels are relatively low for social tenants. Research by Professor John Hills of the LSE found that in 2006 only 32 per cent of social tenant householders were in paid employment and that 70 per cent of social tenants had incomes within the poorest two fifths of the income spread. Out of 4 million tenants within the social housing system, only a few thousand annually move to get work in another location.

Already Cameron’s policy initiative has been critiqued as likely to divide diverse communities that have been in place for many decades. A greater ‘churn’ of long-standing social tenants might adversely affect the kind of community cohesion and development on estate that the Prime Minister’s Big Society idea seeks to encourage. Families would have to change their approach to employment and to education for their children. Recent research by LSE Professor Anne Power into low income housing estates in Hammersmith and Fulham, found that “council estates need anchoring” – which certainly would not be encouraged by these proposals.

Finally, one frequently unremarked upon aspect of the housing market is the very large number of unoccupied homes across the country. In 2009, emptyhomes, an independent charity, estimated that nearly 651,000 homes lay empty in England , that is nearly 3 per cent of the entire housing stock. Of these, nearly 35,000 were owned by local authorities. This number is slightly less than the sum of all new dwellings that have begun construction in England since 2005.

If government was able to leverage this vast stock of unused housing stock, or to encourage their sale to social housing landlords, then this might go some way to alleviating pressure on the large social housing waiting list. However, the new government has already stressed that it is much more interested in constructing new homes rather than making better use of the existing stock. On the 9th of August, Housing Minister Grant Shapps announced that the government would be introducing a bonus scheme for new homes. Government would match the council tax raised on each new house built over the next six years. As the majority of homebuilding is by private developers, this is unlikely to do a great deal to alleviate the waiting list for social housing.

The gvts proposals demonstrate that they view poorer people and social housing as units rather than as people, homes and communities. I wonder if there are any stats for the number of social homes that have been demolished under the aegis of ‘redevelopment’ and that are not replaced when the ‘redevelopment’ falls through? Such a scheme is happening to my community, where the developers and the ludicrously awful housing trust expect that £1.3 million flats are going to sell on a social housing estate. Until people in power stop looking at graphs and start taking a positive interest in reality the poor will continue to be shuffled about. And resentment builds.