Benedict Dellot argues for the need to support young entrepreneurs. Data shows there is a big gap between the number of 18-24 year olds indicating they want to start a business versus those that have attempted, and that many are giving up shortly after starting up. Government should emphasise the importance of finance and creating a business-plan, among other support initiatives, in order to realise an ‘aspiration nation’.

Benedict Dellot argues for the need to support young entrepreneurs. Data shows there is a big gap between the number of 18-24 year olds indicating they want to start a business versus those that have attempted, and that many are giving up shortly after starting up. Government should emphasise the importance of finance and creating a business-plan, among other support initiatives, in order to realise an ‘aspiration nation’.

Speaking in Milton Keynes last week, David Cameron restated his belief that the surest way for Britain to survive in today’s global race is to enable more young people to ‘fulfil their aspirations.’ Though talking primarily about apprenticeships at the time, he was also sure to be referring to the need to help more young people start up their own businesses.

The government has shown a real commitment to this cause. Alongside partners, it has created the StartUp Britain campaign, to encourage more young people to consider starting up in business; initiated MentorsMe, a UK-wide initiative helping fledgling entrepreneurs find supportive mentors; and implemented several schemes to open up more sources of finance to young people. In a similar vein, universities and various non-state organisations have expanded their own enterprise support initiatives in recent years.

Such commitment to supporting young entrepreneurs is to be welcomed. Enabling young people to start up and run successful ventures not only helps the entrepreneurs make a living themselves, it also creates new jobs for others, contributes to economic growth and stimulates innovation in markets. Without actively encouraging more young people to start up in business there is a danger that we will lose the kind of creative destruction that the UK economy needs to evolve and thrive.

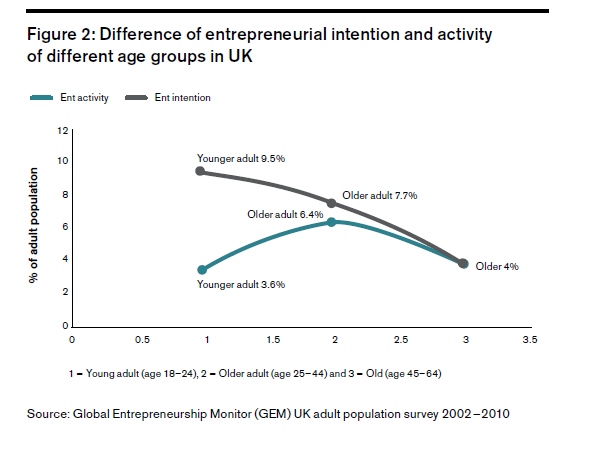

It is of some concern then that there a number of issues holding young enterprises back. First, there is a large gap between the number of young people who say they wish to start a business and the number actually doing so. According to RBS commissioned analysis of GEM survey data by Professors Mark Hart and Jonathan Levie, while 9.5 per cent of 18-24 year olds say they wish to start a venture, only 3.6 per cent have taken the plunge. Second, many of those who do actually start up in business cease trading not long afterwards. According to the same research, as many as a third of young entrepreneurs drop out within a year of starting up.

So what can be done to turn this situation around? While supporting the broad thrust of the steps already taken by the government, the RBS/RSA report released last week argues that any further efforts to stimulate young enterprise in the UK need to be grounded in a better understanding of the new ways in which young people are starting up in business. Indeed, our interviews with dozens of young entrepreneurs suggest that certain young enterprise support initiatives may be geared towards supporting one ‘style’ of entrepreneurship at the expense of less conventional ones.

For example, while the government may emphasise the importance of finance to the start-up process, we find that many young people are in fact reticent about taking out a loan, particularly those who are already saddled with student debt. Similarly, many of the young entrepreneurs we spoke with said they derived very little value from business planning – yet writing lengthy plans is still strongly encouraged by certain enterprise support organisations.

More broadly, we find that the language and imagery of the ‘entrepreneur’ endorsed by some support initiatives may serve to push young people away, particularly those in the creative and entertainment sectors who do not tend to associate themselves with the label of the entrepreneur. The danger is that they then disregard valuable enterprise support that may have otherwise helped them reach their potential.

These may seem like minor shortcomings, but taken together they have the potential to derail the entrepreneurial journeys of thousands of young entrepreneurs. If we are serious about helping more young people into business then we need to begin challenging outdated stereotypes and reengineering enterprise support initiatives to go with grain of young entrepreneurs’ real experiences and preferences. Only by doing so will an ‘aspiration nation’ ever be realised.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Benedict Dellot is a Senior Researcher within the Enterprise team at the RSA’s Action and Research Centre. His recent work has looked at support for young entrepreneurs, the importance of informal economic activity to business growth, youth unemployment and ‘holistic’ approaches to treating long-term unemployment. Alongside his work at the RSA, Ben sits on the UK’s Hidden Economy Expert Strategy Group.