The government introduced legislation requiring employers to auto-enrol their workers in pension schemes, hoping that this ‘nudge’ will reduce the pensions gap – the difference between retirement savings and the minimum amount a pensioner will need to avoid poverty. Sandy Pepper summarises research suggesting otherwise. In the majority of cases, auto-enrolment contributions will not be high enough to provide the level of retirement income that most people require, because auto-enrolment assumes, and indeed in a sense encourages, apathy rather than engagement.

The government introduced legislation requiring employers to auto-enrol their workers in pension schemes, hoping that this ‘nudge’ will reduce the pensions gap – the difference between retirement savings and the minimum amount a pensioner will need to avoid poverty. Sandy Pepper summarises research suggesting otherwise. In the majority of cases, auto-enrolment contributions will not be high enough to provide the level of retirement income that most people require, because auto-enrolment assumes, and indeed in a sense encourages, apathy rather than engagement.

In October 2012, new pensions legislation, known as “auto-enrolment”, was introduced in the United Kingdom. It requires every employer automatically to enrol UK workers into a workplace pension scheme if they are over 22 years of age and earn more than £9,440 a year. The government hopes that auto-enrolment will play a big part in fixing the pension gap, the difference between retirement savings and the minimum amount that future pensioners will need to avoid poverty in old age. However, recent research which I carried out with Rebecca Campbell, a PhD student at the LSE, in conjunction with Thomsons Online Benefits, a company which helps organisations to maximise the investment they make in their pension and benefits programmes, suggests otherwise.

The idea of auto-enrolment has its origins in the “nudge” principle, made famous by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, who draw on ideas from behavioural economics and economic psychology. The thinking goes like this: If employees are given the option of joining a pension plan, then many will not choose to opt-in and hence will not make pension contributions. In contrast, if as a matter of course workers are enrolled in a pension plan and employee contributions are deducted automatically, then few will bother to reverse the decision and opt-out. In this way it is hoped that employees will “voluntarily” accumulate enough retirement savings to ensure that, along with more modest future state pensions, they will be able to live comfortably in retirement.

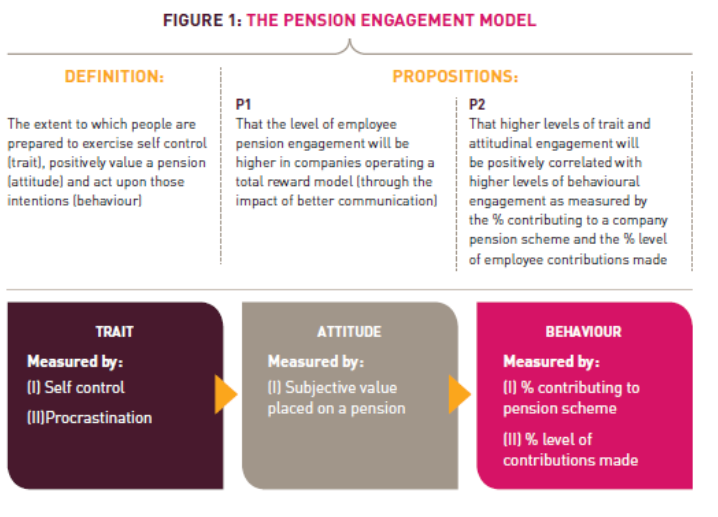

The research conducted by the LSE and Thomsons shows that things are not so simple. In the majority of cases, auto-enrolment contributions will not be high enough to provide the level of retirement income that most people require. Because auto-enrolment assumes, and indeed in a sense encourages, apathy rather than engagement, few pension scheme members will realise that they need to make additional retirement provision as well. The LSE and Thomsons research considered “pension engagement” from three perspectives: as a personality trait, as an attitude, and as a behaviour (see figure 1).

In conducting the research, two parallel groups of employees were sampled, one with around 450 employees working for companies which operate total reward systems, along with a control group of 500 other employees. A “total reward system” is one in which all elements of pay and benefits are valued and reported to employees, including pension and other benefits. This is typically accompanied by very extensive communications by employers with their workforces on pensions and other benefits issues.

It was discovered that members of the control group, i.e., those where total reward systems were not in operation, were in general less well informed about their pension contributions, their investment fund options and what they would receive by way of pension following retirement. An employee in the total rewards group was 17% more likely to be a member of their workplace pension scheme, irrespective of salary level, than a member of the control group. The control group was less well informed about pensions, with 25% of them not knowing how much their employers were contributing on their behalf, compared to only 10% in the case of the total reward group. Almost 17% of the control group didn’t know how much they were contributing to their pensions themselves, compared to 8% of the total reward group. The total reward group was also more likely to understand the tax advantages of pensions than the control groups.

In addition, the total reward group was much more likely to promote the advantages of pension plans. The net-promoter score (see here) of the total reward group, calculated in response to the question “how likely is it that you would recommend to a colleague that they should participate in a pension scheme?”, was 20.5, in contrast with the control group whose score was -10.2, a very significant difference of 30 percentage points.

Intriguingly, although the total reward group’s knowledge of pensions, assessed objectively, was much better than that of the control group, members of the total reward group rated their knowledge less highly. As Confucius is reported to have said: “true wisdom is knowing what you don’t know”.

Copies of the research publication “The impact of a total reward approach on workplace pension engagement” by Alexander Pepper and Rebecca Campbell, published by Thomson Online Benefits and the London School of Economics and Political Science, are available on request.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr Alexander (Sandy) Pepper is Senior Fellow in the Department of Management at the London School of Economics.