In devolved systems, people may be unsure about which government does what and so who is responsible for policy outcomes. Sandra León and Lluís Orriols use a survey experiment on responsibility attribution surrounding the NHS in Scotland and Wales, and point to the role of partisanship and identity as cognitive guides in attributing credit and blame.

In devolved systems, people may be unsure about which government does what and so who is responsible for policy outcomes. Sandra León and Lluís Orriols use a survey experiment on responsibility attribution surrounding the NHS in Scotland and Wales, and point to the role of partisanship and identity as cognitive guides in attributing credit and blame.

A Scotsman’s reader recently sent a letter to the newspaper titled “Don’t blame the SNP, blame Westminster austerity” and which included the following statement:

Years of austerity have made it difficult for the SNP government to be effective. Blame Westminster for difficulties in maintaining good NHS services, meeting environmental targets and caring for young and old. If you think public sector standards are bad here, you need to visit England more often. (Letters section, The Scotsman, 6/03/2019)

Blame attribution on policy outcomes is a controversial issue in democratic theory. One of the most celebrated promises of representative democracy is that free, competitive, and fair elections should enhance good government. The mechanism goes as follows: as incumbents may anticipate the electoral costs associated to deviating from the interests of the electorate, they will end up being responsive to voters’ demands in order to avoid electoral punishment.

However, elections can only effectively discipline politicians if voters can discern to what extent incumbents are responsible for policy outcomes, and that capacity varies according to the institutional context. Devolution is one of the institutional characteristics in a political system that complicates clarity of responsibility, as there are different levels of governments responsible for different policy areas and, in turn, potentially blameable for policy outcomes.

Think about healthcare. Although the NHS is a devolved power, the Scotsman’s reader considered that Westminster was responsible for poor healthcare services. This posits an interesting question: why are some individuals more prone to accuse Westminster than Holyrood? What are the determinants of blame attribution? The aim of our investigation is precisely to shed some light on how citizens end up attributing responsibility for policy outcomes in federal or decentralised systems.

We argue that vertical fragmentation of powers which characterises devolved settings provides an opportunity structure for individuals to engage in a blame-attribution game between the different levels of government. Our hypothesis is that political identities play a key role in blame-attribution. We claim that citizens are not neutral in their judgements, but filter them through a group-serving bias: giving credit for good performance to the group they identify with, and blaming the out-group for poor outcomes. Although research has studied the role of partisanship as a source of attribution bias, it has largely ignored another salient identity in politics: the national one.

In our investigation we try to test to what extent individuals’ bias in responsibility assignments respond to their in-group preferences, namely party affiliation and national identity. Indeed, according to our expectation the Scotsman reader would probably be someone who is emotionally attached to the SNP and (or) to Scottish identity.

In order to test our expectations we conducted survey experiments on responsibility attribution for the NHS in Scotland and Wales in the run-up to the 2015 general election. The experiment consisted of randomly providing a positive or negative statement made by experts about changes in healthcare outcomes, followed by a question about who is mainly responsible for the change. More specifically, the positive and negative treatments were worded as follows (positive treatment in brackets): “Many experts say that healthcare in Scotland/Wales has generally worsened [improved] over the last year; for example the waiting times for patients in urgent services are now longer [shorter] and time allocated to patients in primary care has decreased [increased]”.

Respondents were then asked to locate on a 7-point scale the degree of responsibility of the central and regional governments (being 1 regional government and 7 central government).

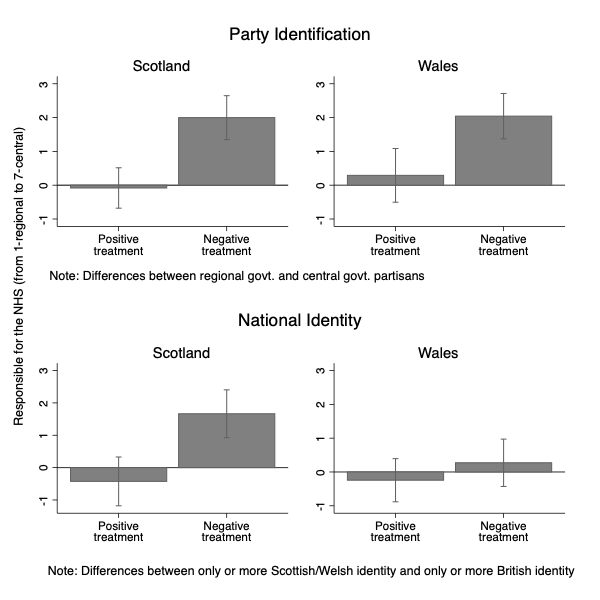

Our findings show that both party identification and national identity are drivers of attributions of responsibility in Scotland and Wales. Our results also indicate that partisanship has a more prominent and encompassing effect than national identity. Some of the empirical findings are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The effect of party identification and national identity on responsibility attribution for NHS outcomes

Note: The figure shows the mean differences on the NHS responsibility scale (1-regional authorities to 7-central authorities) between regional and central government partisans (top line) and between British and Scottish/Welsh identity. The spikes indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

Note: The figure shows the mean differences on the NHS responsibility scale (1-regional authorities to 7-central authorities) between regional and central government partisans (top line) and between British and Scottish/Welsh identity. The spikes indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

The two graphs above show the differences in attribution of responsibility between individuals who identify with regional incumbent party(ies) (we label them as regional government partisans) and individuals who identify with incumbent parties at the central level (central government partisans).

Results are consistent with the claim that citizens make responsibility assignments that are coherent with their party alignment. But this only occurs for the negative treatment only. Individuals who identify with parties other than the Conservative Party or the Liberal Democrats (that formed the central incumbent coalition at the time of the experiment) hold the central government more responsible for poor NHS outcomes than those identified with the Conservative Party or the Liberal Democrats. In summary, empirical evidence suggests that people are more willing to filter responsibility assignments through the lenses of partisanship when things go wrong.

The two bottom graphs in Figure 1 show that differences in responsibility attribution between those more or only identified with the region and those who feel mainly British are only significant for the negative treatment and for the Scottish sample. In Wales, attribution of responsibility for the results of the NHS is not significantly moderated by national identity, regardless of the positive or negative nature of the treatment. Overall, our investigation indicates that it is partisanship, and not national identity, the most important in-group bias driving responsibility assignments.

These results have important implications for the operation of representative democracy and electoral accountability. If voters filter their responsibility judgements through the lenses of partisanship and national identity, incumbents may end up being rewarded or punished by the electorate in a way that is unrelated to policy outcomes. As a result, the incentives of politicians to be responsive to the electorate’s preferences may ultimately fade away.

Our findings also have important implications for the current debate on British devolution. Constitutional amendments since the late 1990s have turned the UK into one of the most heterogeneous institutional settings amongst European countries. The ongoing nature of the process of devolution in the UK, illustrated by recent reforms in Wales and Scotland as well as by the process of English devolution to local combined authorities, will certainly complicate responsibility assignments. How will British citizens cope with that complexity? Our research indicates that partisan alignments and national identity will very likely act as cognitive guides for individuals in an increasingly complex institutional setting.

_______________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Electoral Studies.

Sandra León is Senior Lecturer at that University of York.

Sandra León is Senior Lecturer at that University of York.

Lluís Orriols is Associate Professor at University Carlos III, Madrid.

Lluís Orriols is Associate Professor at University Carlos III, Madrid.