As unemployment continues to rise to near-record levels, the reductions in child poverty seen under Labour may now be reversing. New research from Kate Bell and Jason Strelitz finds that previous welfare reforms did not go far enough in reforming work itself. They argue that to really tackle poverty, policy makers must focus on improving working conditions and help people to find a better balance between paid employment and childcare.

As unemployment continues to rise to near-record levels, the reductions in child poverty seen under Labour may now be reversing. New research from Kate Bell and Jason Strelitz finds that previous welfare reforms did not go far enough in reforming work itself. They argue that to really tackle poverty, policy makers must focus on improving working conditions and help people to find a better balance between paid employment and childcare.

Research published by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) last month has shown that the reductions in child poverty previously seen in recent years are now in reverse. Figures published on Wednesday are expected to see a further rise in unemployment, and the Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development have pointed to a ‘slow painful employment contraction.’ Now seems an inauspicious time to launch a report seeking to reinvigorate the child poverty agenda, but in Decent Childhoods: Reframing the Fight to End Child Poverty we argue that this is exactly the moment in which we need to reflect on how we can recover the sense of excitement felt when Tony Blair in 1999 set out a pledge to end child poverty by 2020.

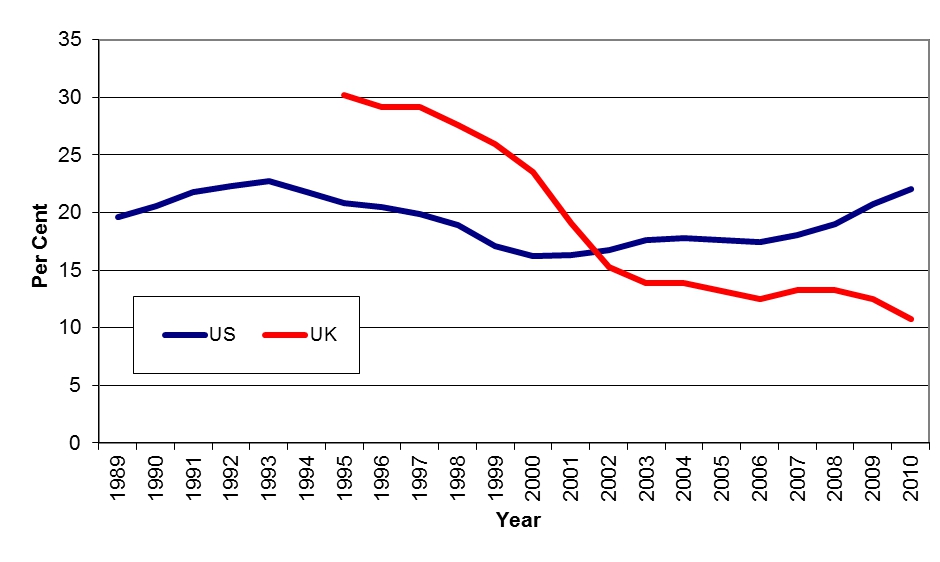

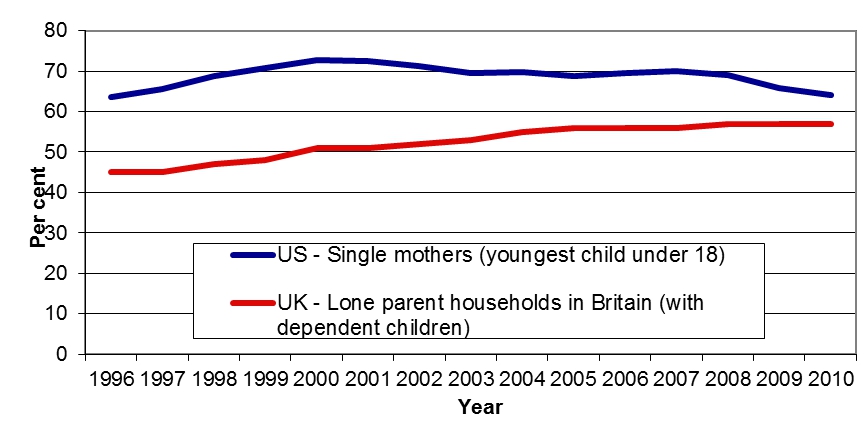

Our report examines what happened since that pledge was made, and reflects on the lessons learnt. While we don’t attempt a comprehensive analysis of all policy interventions, a task recently undertaken thoroughly by the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, we do show that significant gains were made under Labour. As Figure 1 shows absolute poverty among families fell dramatically in the UK. While Labour has been accused of achieving these gains only by increasing family financial support, the rate of parental employment also increased, particularly for lone parents. While ‘U.S. style welfare reform’ is often hailed as the solution to the UK’s poverty problem, rates of lone parent employment in the UK in the last decade increased at a similar rate to the much lauded increases in the U.S. following the 1990s reforms (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 – Absolute poverty in the UK fell faster than in the US

Source: Adapted from Waldfogel and Smeeding (2010); data from Annual poverty reports from the US Census Bureau (2010) and UK Department for Work and Pensions (2010).

Figure 2 – Single Parent employment in Britain increased at a similar rate as in the US (though from a lower base)

Source: UK figures, Labour Force Survey data; US figures

These figures illustrate that policy can make a difference; there’s no need for defeatism about the possibility of improving the lives of families on low incomes. But we have identified two major areas where the approach fell short. Firstly, the child poverty agenda barely registered on the public consciousness, as Figure 3 shows. Without a significant constituency for change, securing the agenda relied on the good will of a policy elite, a will that the IFS figures suggest is rapidly disappearing.

Figure 3 – Importance of Poverty to the British public, 1997-2009 – Percentage citing issues as most important facing Britain today, month by month

Source: Mori Issue Index (data for some months is missing).

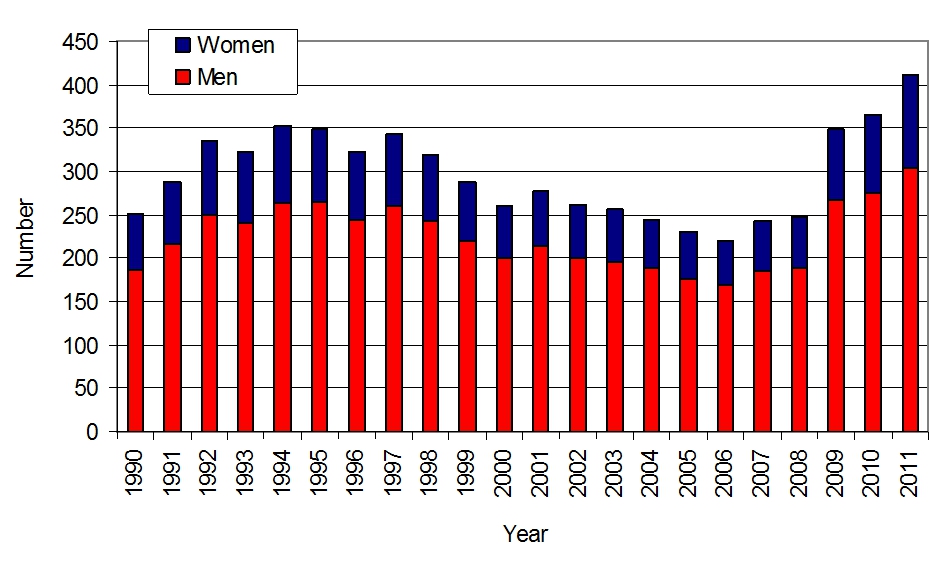

Secondly, we argue that the scale of change required to deliver the target was not fully grasped. In particular the focus on ‘welfare reform’ was not accompanied by a focus on reforming work itself: as the Resolution Foundation have shown, wages at the bottom and the middle have increasingly failed to keep pace with those at the top. Half of all children are in working households, and without the heavy lifting performed by tax credits, in work poverty would be significantly higher. Too many people experience a ‘low pay, no pay’ cycle, with half of all men making a new claim of jobseekers allowance, and a third of all women, having made a previous claim within 6 months.

Figure 4- Passing in and out of work, 1990-2011 –Number of men and women making a new claim for Jobseeker’s Allowance who were last claiming this benefit less than six months previously

Source: Figure 2 in Chris Goulden (2010) Cycles of poverty, unemployment, and low pay Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

How can we turn this around? We argue that a focus on ‘the poor’ failed to recognise that the many of the problems of those living in poverty are the same as those just above the poverty line; that tackling poverty requires improving working conditions and job security across the board. We suggest that a more positive concept of Decent Childhoods for all would encourage a broader focus on the type of change that will be necessary to deliver this; a fairer distribution of the rewards from paid work, a serious attempt to tackle regional disparities in employment, and a better balance between paid work and caring for children, so that families do not have to face a choice between income poverty and time poverty.

The dire employment figures mean that the primary public policy focus of the next five years must be how to return to economic growth and full employment. Too often ‘ending child poverty’ has been seen as an afterthought, an optional extra for when these ‘serious’ economic issues have been dealt with. But if not to deliver decent childhoods for all, what exactly are we after when we look for policies to deliver economic growth? Now is the time that these questions should be central.

Decent Childhoods: Reframing the fight to end child poverty is published today.

Please read our comments policy before posting.