There has been much recent talk about the possibility of the Coalition government falling before the parliamentary term is up. Chris Hanretty uses a quantitative statistical model to suggest that this is indeed probable, and that the best prediction indicates the government will fall in October 2014.

There has been much recent talk about the possibility of the Coalition government falling before the parliamentary term is up. Chris Hanretty uses a quantitative statistical model to suggest that this is indeed probable, and that the best prediction indicates the government will fall in October 2014.

If I were David Cameron or Nick Clegg, I’d be fairly worried on or around the 25th of October 2014. If models of coalition duration are right, that’s when their government will finally run out of steam. That’s despite their commitment to fixed term parliaments, ably dissected by Patrick Dunleavy earlier this week. Institutional innovation is a fine thing – and that particular innovation probably bought the government ten months of extra life – but it can’t prevent this coalition government from following the patterns of politics shown across the rest of Europe.

Britain is somewhat unusual in its devotion to single party government. For those who, like me, study comparative politics, the study of coalition government is where the action lies. Part of that study concerns the birth and life of coalition governments: predicting after the election which of the myriad possible coalitions will form, and understanding, during the government’s life, how coalition tensions arise, are accommodated, and are defused.

But part of that study of coalition government also concerns the death of coalitions — or, to use the more studiedly neutral term popular in the literature, ‘cabinet termination’. The great knock against coalition government has always been that it is unstable. Coalition cabinets should have a shorter duration, other things being equal, than single party governments.

That claim has been subject to particular testing by political scientists – in particular, testing through quantitative statistical methods that enable us to make bold (perhaps even foolhardy) conjectures about how long particular cabinets will last.

It’s not necessary to know the precise details of the model I used to generate the above prediction (Weibull regression, for those of you playing along at home). Suffice it to say that this particular model is an example of duration analysis. Duration analysis is used in lots of fields, but with different names. Engineers might talk about time-to-failure models. Epidemiologists might talk about survival models. In all cases, we’re trying to make predictions about the time until a particular event – failure of a key mechanical part, or death due to disease. We try to do so on the basis of a number of predictors, or covariates. But instead of factoring in the tensile strength of the metal used in our part, or the virulence of a particular disease, we use features of the coalition to predict its duration.

The predictors I use come from the standard text on coalitions. They include factors related to

- the structure and composition of government (whether or not it has a majority, is a coalition, is minimal winning, is ideologically connected, and contains the party with the largest bargaining power);

- the institutional rules of the polity (whether investiture votes are required; the degree of opposition influence; whether cabinet decisions require unanimity; whether the prime minister can dissolve parliament; whether the parliament is bicameral or not; whether the system is semi-presidential or not; and the maximum possible duration of a government), and

- the party system (party system: the effective number of parliamentary parties; whether or not the government is conservative or not; the ‘effective number of issue dimensions’)

I trained a model using these predictors on data from western European governments, and then generated new predictions for the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition.

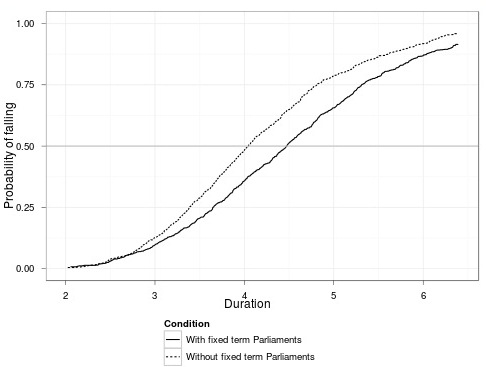

For ‘normal’ (i.e., single-party) British cabinets, this kind of exercise would be sorely uninteresting. Such models sometimes predict cabinets that are nigh immortal, and which in any case would last far longer than the maximum five-year term. But for the current cabinet, the model generates predictions about probability of failure that are shown below.

The figure shows two lazy S-shaped curves. The solid curve represents our best prediction for the government as it stands. The cumulative probability of the cabinet failing rises from negligible during the first two years, before rising steeply between the fourth and the fifth year.

The cabinet has a two-thirds probability of falling before the end of the fifth year — or, what is equivalent, a one-in-three chance of going the distance. Our best prediction about the duration of the cabinet has it falling in October of 2014.

Did the new rules on fixed term parliaments improve the odds? The dotted curve shows our best prediction under the previous rules on dissolution. Without fixed-term parliaments, our best prediction about the duration of the cabinet is slightly more pessimistic — in the spring of 2014.

Does cabinet termination in autumn 2014 mean a general election in 2014? Not necessarily. Even if our model is absolutely correct – and remember, all models are wrong, though some are useful – then we haven’t said anything about the consequences of cabinet termination. A likely consequence is an immediate election, but other options – caretaker minority Conservative administration – remain possibilities.

Still, this kind of prediction offers us a useful baseline to work from. If you believe that autumn elections are unlikely, shift the curves to the left. If you believe that Cameron and Clegg have greater reserves of intestinal fortitude than most European politics, shift the curves to the right. But this kind of exercise is certainly a useful corrective to the prevailing wisdom. Right now, the betting markets imply a 2/3rds probability of a general election in 2015 and not before. Given the predictions of this model, the bookies seem to be fairly bullish about the cabinet’s survival. Anyone who wants to bet on a 2014 election faces fairly good odds. Perhaps the bookies just want to offer Cameron and Clegg a nice hedging opportunity?

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Chris Hanretty is Lecturer in Politics at the University of East Anglia. This post is based on research featured in a joint University of East Anglia/Institute for Government publication, The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions. Data and R code used to generate the figures can be found here.

1 Comments