Gabriel Ahlfeldt presents findings from a recent research report showing that property prices are generally higher inside conservation areas. The regulation is good news for policymakers as it ensures collective action in maintaining neighborhoods, making free-riding much harder to do.

Gabriel Ahlfeldt presents findings from a recent research report showing that property prices are generally higher inside conservation areas. The regulation is good news for policymakers as it ensures collective action in maintaining neighborhoods, making free-riding much harder to do.

Since the 1960s, over 9,800 Conservation Areas have been designated in England with the aim of preserving local historic or architectural character. It is argued that the specific heritage value of these areas needs to be protected in the interest of society, including current and future members.

Valuing this heritage and the policies put in place for its preservation is challenging. The key problem is that what these areas deliver to their surroundings – and society as a whole – is not directly traded on the market. And since there are no directly observable prices, it is difficult to put a number on people’s willingness to pay for their effects.

In a recent report commissioned by English Heritage we have tried to unpick the economics of Conservation Areas using a combination of quantitative and qualitative techniques.

We therefore looked at observable market outcomes – as reflected in more than 1m property transactions across England since 1995. Exploring more than 8000 conservation areas, we found that property prices are generally higher inside conservation areas – about 9 per cent controlling for other factors. Equivalently important, we were interested in how the value of these historically and architecturally particular building spills over to their surroundings. I believe an assessment of the external effects of heritage buildings must be at a heart of a preservation policy evaluation. The aesthetic quality of a building is a public good. It can be enjoyed free of charge by anyone living near to the building or even just passing by. Preserving this external value, which goes beyond the value the owner might attach to its property, is a key motivation for the designation of conservation areas.

Our results suggest that such an external value exists. Figure 1 illustrates how – controlling for other factors – property prices tend to increase the further one moves towards a conservation area. Prices increase up to 3 per cent close to a conservation area. The effect diminishes with distance and disappears after about 600 meters.

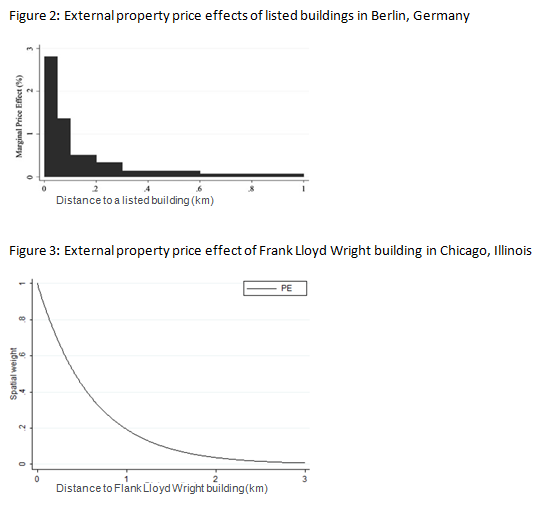

These effects closely resemble the results of one of my previous studies investigating the effects of about 16,000 listed buildings in Berlin, Germany. Figure 2 again points to a very similar pattern, both in terms of the percentage effect on prices as well as in the spatial impact. The effects become even stronger when focussing on particularly important prestigous buildings. In a recent study, I had a look at the external property price effects of 25 residential buildings by world famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago Oak Park. The result of this analysis: An increase in prices of nearby houses of up to 5 per cent and even wider impact area than an average conservation area in England or an average listed building in Berlin.

Is it likely that these effects are really caused by the architecture of these buildings or may other (unobserved) factors such as a privilege location account for them? In the report for English Heritage we have analyzed 111 in-depth residential interviews conducted in 10 conservation areas to answer this question. Figure 4 compares our computed property price premiums in conservation areas relative to their surroundings to how residents ranked the attractiveness of the buildings in these areas. Evidently, our results suggest that the premium people pay for living in conservation areas rises with a neighborhood’s aesthetic quality.

All this is compelling evidence that there is a willingness to pay for the aesthetic quality and the historic character of the neighborhood, at least by those living in these areas.

Are there any downsides? For homeowners, Conservation Areas pretty significantly constrain the degree to which properties can be altered. We might expect these constraints could cause property values to decline following a designation. However, looking at over 900 recent designations across England, we couldn’t find any significant effect on prices. Owners we interviewed also generally express positive attitudes towards the planning constraints that come with designation, and the planning system more generally.

This is good news for policymakers, since it suggests Conservation Areas secure local social benefits without costs to individual homeowners. Rather, designation captures externalities that are then capitalised into house prices. In doing so, Conservation Areas solve a form of prisoners’ dilemma. If all local homeowners look after their historic houses, everyone is better off. But individual homeowners might be tempted to let their properties go to seed, while free-riding off nearby properties’ ‘character’. A regulation that ensures collective action makes such free-riding much harder to do.

It’s harder to say whether more conservation area designations are in the interest of society as a whole. For instance, we don’t know if Conservation Area designations limit the supply of new housing in some regions, or the country as a whole. If they do, too many designations may create gilded cages – beautiful towns in which living space becomes unaffordable for the average household. More work needs to be done to answer this question.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr. Gabriel Ahlfeldt joined the Department of Geography and Environment in October 2009 as a Lecturer in Urban Economics and Land Development. Dr. Ahlfeldt is an Affiliate of the Spatial Economics Research Centre (SERC) and an associate of the Centre for Metropolitan Studies, Berlin. His research concentrates on the effect of large transport projects and architectural developments on local house prices, local political preferences and urban structure.