Lucinda Platt and Ross Warwick investigate recent claims that minority ethnic groups are being worse affected by COVID-19. Drawing on new IFS research, they show that accounting for group differences in age and geography, mortality is disproportionately high for all minority groups, with black Africans particularly badly affected. At the same time, some groups, particularly Pakistanis and Bangladeshis face worse economic impacts as a result of the lockdown.

Lucinda Platt and Ross Warwick investigate recent claims that minority ethnic groups are being worse affected by COVID-19. Drawing on new IFS research, they show that accounting for group differences in age and geography, mortality is disproportionately high for all minority groups, with black Africans particularly badly affected. At the same time, some groups, particularly Pakistanis and Bangladeshis face worse economic impacts as a result of the lockdown.

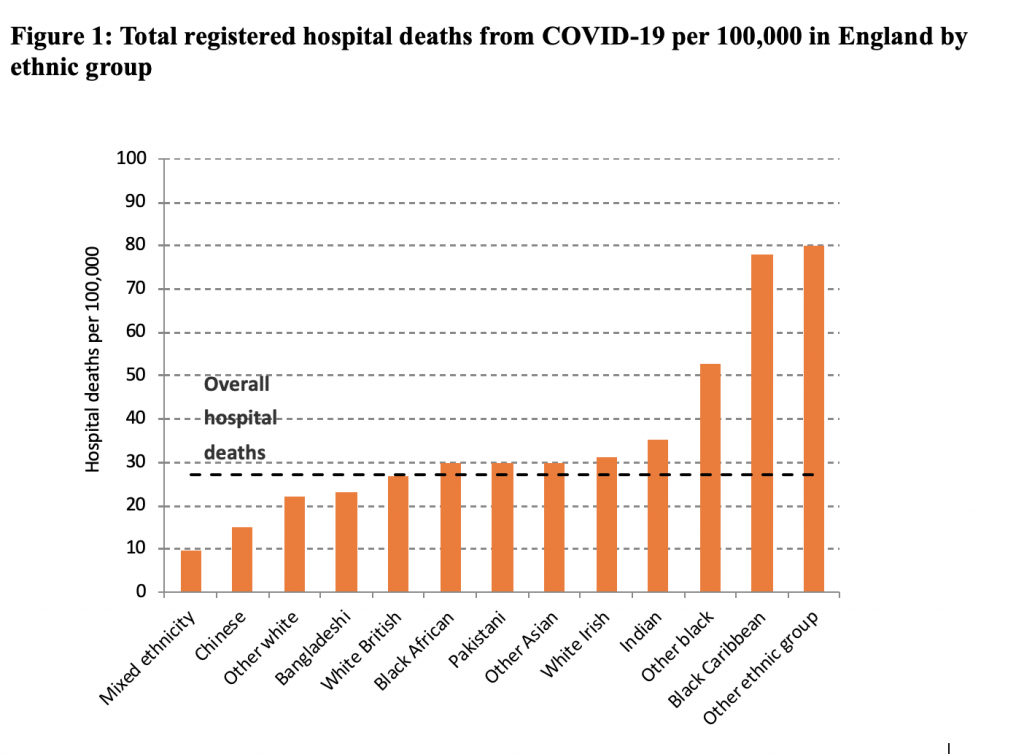

It has been repeatedly suggested that minority ethnic groups are overrepresented among those dying from COVID-19. Comparing hospital deaths to population size for the different ethnic groups shows that some minorities have suffered fewer deaths than the population overall, whereas groups like the black Caribbean population have suffered far more (Figure 1).

Figure based on authors’ calculations using population data from 2011 ONS Census of England and Wales and NHS England COVID-19 hospital death figures by ethnicity as of 21 April 2020.

Figure based on authors’ calculations using population data from 2011 ONS Census of England and Wales and NHS England COVID-19 hospital death figures by ethnicity as of 21 April 2020.

But these headline numbers paint only a partial picture for three reasons. First, COVID-19 deaths are strongly age-related, and ethnic groups have different age profiles and therefore different expected risks. In fact, most minority groups are younger on average than the white British majority and should therefore be less at risk, all else equal. At the same time, deaths have not been evenly distributed geographically, with rates higher in urban areas and areas that tend to have higher shares of many minority groups. Third, not all deaths have taken place in hospitals. While some deaths have taken place at home, the largest number of deaths outside hospitals have taken place in care homes, where residents are over 95% white.

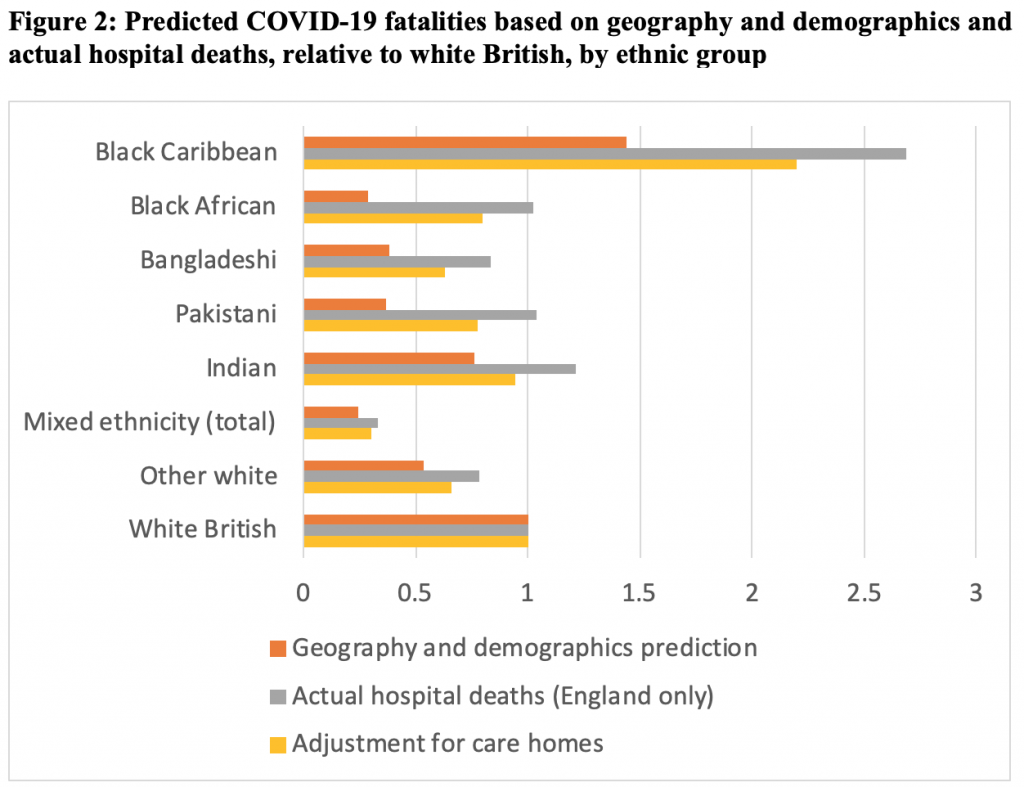

Figure 2 shows ‘expected’ deaths for each minority group relative to the white British majority, if risks were constant for age and sex and area of residence, based on the most recent ONS data on COVID-19 deaths. This orange bar shows, for example, that Black Caribbeans who have a relatively similar age profile to the white British would have higher predicted rates of death than the white majority – the bar is greater than 1 – based on where they live. The other ethnic groups have much lower expected rates (orange bars less than 1) because they are much younger.

These expected rates can be compared to the relative rates of actual hospital deaths in the grey bar. Since the grey bar is longer than the orange bar for all minorities, this shows that their mortality risk is greater than would be expected on the basis of demographics and geography alone.

Figure based on: ONS weekly occurrences of COVID-19 deaths up to 24 April and PHE hospital death data up to 28 April.

Figure based on: ONS weekly occurrences of COVID-19 deaths up to 24 April and PHE hospital death data up to 28 April.

Finally, the third, yellow bar makes an adjustment to take into account deaths in care homes which are not represented in the hospital figures. While the ethnicity of those who die in care homes is not known yet, the residents of care homes are much more likely to be white than the population overall. The adjustment above assumes that the ethnic composition of care home deaths is in line with the ethnic composition of care home residents overall.

This adjustment therefore reduces the gap between actual and expected deaths. Nevertheless, all minorities continue to face higher risks of death than we would expect on the basis of their age and where they live. For Black Africans, the rates are nearly three times those that would be expected, while for Pakistanis they are two times, and for Bangladeshis and Black Caribbeans one-and-a half times expected rates. These findings are consistent with recently published ONS research, which used more aggregated groups and geographies.

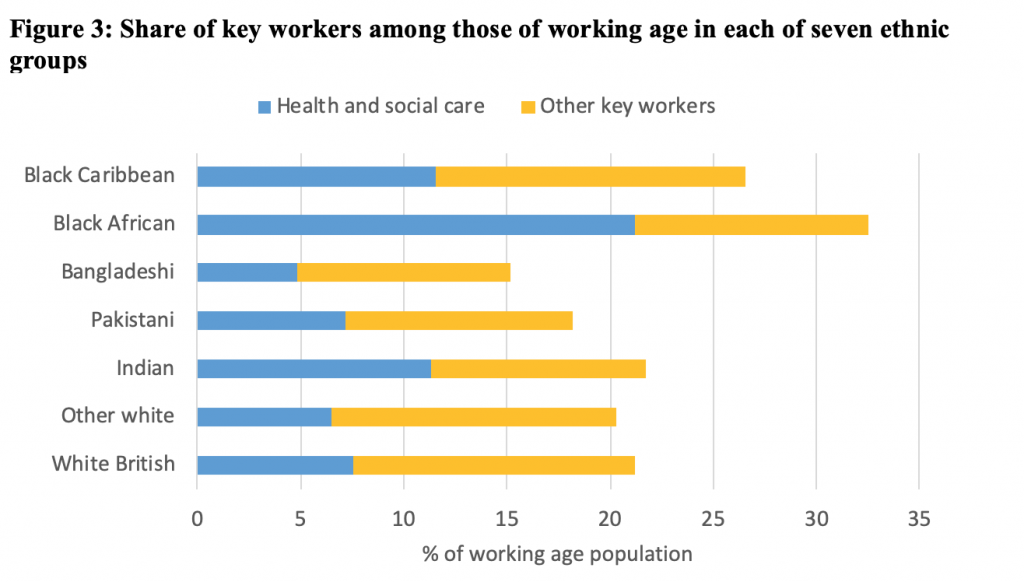

This of course raises the question as to what explains the remaining inequalities. Some groups – particularly Black Africans – are overrepresented in key worker roles (Figure 3). More particularly, Black African women are four times as likely as White British women to be working in social care roles, which have been found to have significantly raised mortality from COVID-19, while Black African men are seven times as like as White British men to be working in such roles. This may be contributing to their exposure to the disease. For others, underlying health conditions, themselves influenced by relative deprivation, may be making them more vulnerable.

Figure based on authors’ analysis of Quarterly Labour Force Survey, quarter 1 2016 to quarter 4 2019.

Figure based on authors’ analysis of Quarterly Labour Force Survey, quarter 1 2016 to quarter 4 2019.

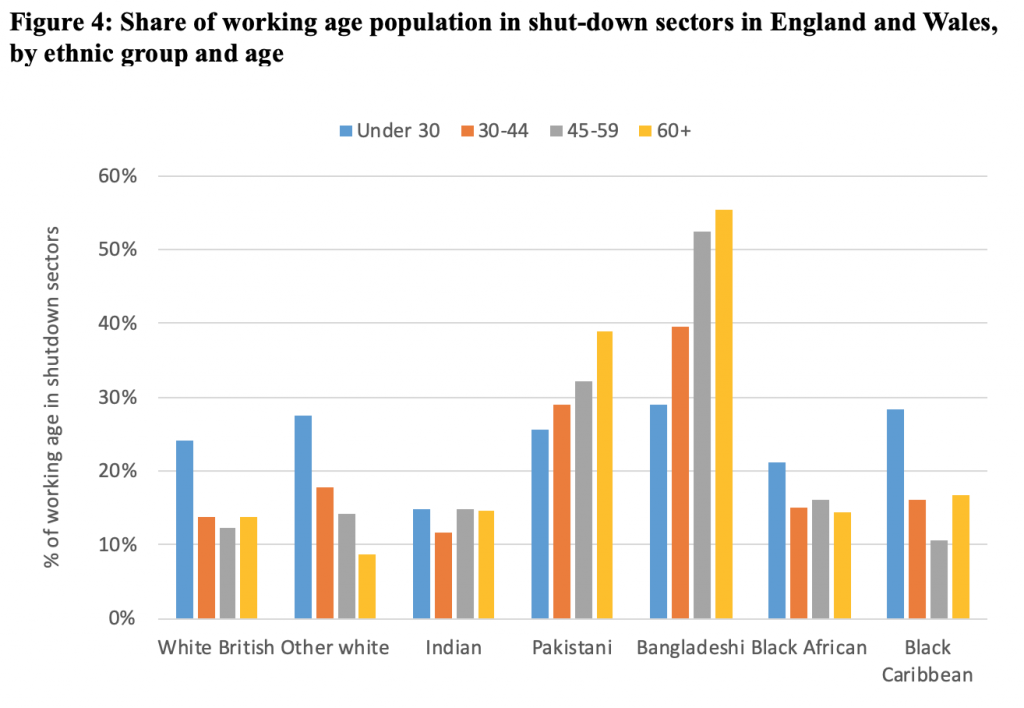

Alongside inequalities in vulnerability to infection, ethnic groups also differ in their economic vulnerability in light of the crisis. The lockdown aims to limit exposure and hence fatalities, but it has come with major economic impacts. Pakistani and Bangladeshi men in particular are heavily over-represented in shut-down sectors. Strikingly, while overall it is younger workers and women who are more likely to be working in shut-down sectors, among Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, more men work in these sectors and the chances of doing so increases with age (Figure 4).

Figure based on authors’ analysis of Quarterly Labour Force Survey, quarter 1 2016 to quarter 4 2019.

Figure based on authors’ analysis of Quarterly Labour Force Survey, quarter 1 2016 to quarter 4 2019.

Incomes may currently be especially uncertain for those who are self-employed, and rates of self-employment are also high amongst Pakistani and Bangladeshi men, with Pakistani men 70% more likely to be self-employed than the White British majority.

How badly individuals and families are affected depends on the extent to which they are buffered by the resources of others in the household or can draw down savings. Bangladeshis, Black Caribbeans, and Black Africans have the most limited savings to provide a financial buffer against losses in income. Only around 30% live in households with enough to cover one month of income, compared with 60% among the White British, Other White, Indian and Pakistani populations.

These findings raise issues for policy relating to how best to protect vulnerable populations. Considering the high rates of health and social care key workers among the groups with the most disproportionate mortality, protecting those working on the frontline, is clearly crucial. The concerns over lack of PPE, including for workers in care homes, or inconsistent applications of standards may be reducing opportunities to minimise the spread of infection.

More broadly, it is vital to recognise the ways that some groups are channelled disproportionately into particular occupational sectors – whether in carework or in self-employed or economically marginal sectors. Addressing the issue of job quality and remuneration for needed but often undervalued jobs for all workers could be expected to go a long way to reducing the inequalities that the current crisis has brought into stark relief.

____________________

Note: the full report on which the above analysis draws was carried out as part of the IFS Deaton Review of Inequality funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

Lucinda Platt is Professor of Social Policy at the LSE.

Lucinda Platt is Professor of Social Policy at the LSE.

Ross Warwick is research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Ross Warwick is research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

When will politics change so that equality is the intentional rationale and measurable outcomes are intentionally demonstrated?

And of course the electorate understand why this rather than individual gain is what is the most critical.