Mette Marie Staehr Harder and Christoffer Bugge Harder examine whether countries led by women applied more extensive measures to combat COVID-19 than those led by men. While they find no indications that the former applied more extensive health responses over time, OECD countries led by women did enact their respective maximum shutdown measures significantly more quickly than those led by men.

Mette Marie Staehr Harder and Christoffer Bugge Harder examine whether countries led by women applied more extensive measures to combat COVID-19 than those led by men. While they find no indications that the former applied more extensive health responses over time, OECD countries led by women did enact their respective maximum shutdown measures significantly more quickly than those led by men.

In spring 2020, a global narrative that female heads of government were better at fighting COVID-19 emerged. One such prevalent narrative was the idea that female heads of government had applied more extensive response strategies than their male colleagues. In a recent study, we show that this is not true: using the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker dataset, we find no indications that female leaders apply more extensive shutdown measures or health responses over time. However, within the period 1 January and 25 June 2020, OECD countries led by women did enact their respective maximum shutdown measures significantly more quickly than countries led by men.

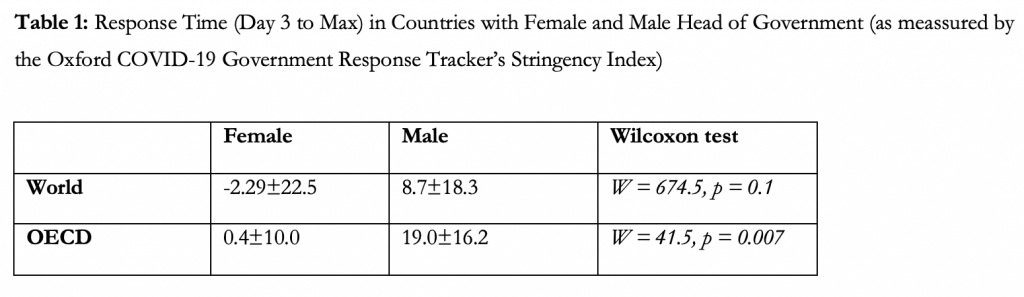

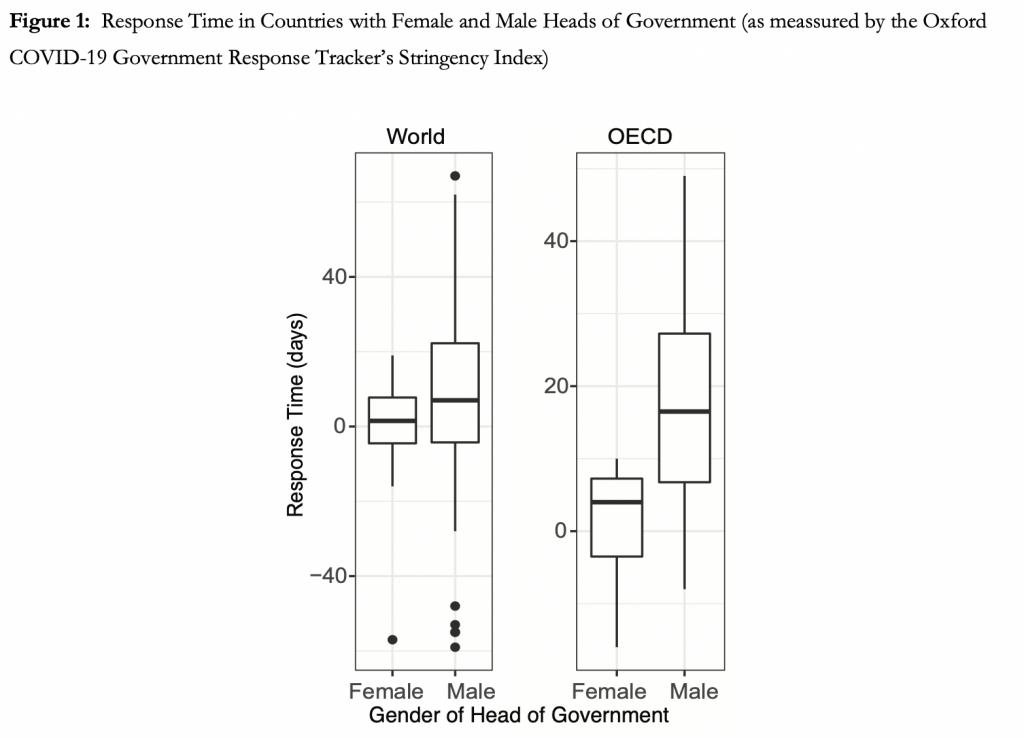

Countries with female heads of government on average enacted their maximal level of shutdown and containment (the dataset’s so-called “Stringency Index”) an average of 0.4 days after their country’s ‘Day 3’ – i.e. the first day a country had three COVID-19-caused deaths. However, countries with male leaders on average took 19 days to reach this level (Table 1).

This difference holds true even when leaving out dual outliers such as New Zealand, which implemented its maximal closure and containment policy more than two weeks before its first day of three COVID-19-caused deaths, and Italy, which was the epicentre of the European outbreak and had a response time of 47 days between its ‘Day 3’ and the date it reached its maximum level of response.

To check the importance of other variables in explaining the gendered leadership difference concerning response time, we test the correlation between response time and a battery of quantitative variables such as median age of the population, health care quality, government expenditure, levels of unemployment, levels of growth, women’s labour force participation rate, and a country score in terms of the level of gender equality as measured by the Global Gender Gap Index 2020. Only the two latter variables correlate with response times, yet our further statistical testing shows that the especially important variable of gender equality is important as a pre-requisite for having a female head of government in a country. It cannot stand alone in explaining the response time.

Our study is part of a ‘first wave’ of studies concerning COVID-19 governance and the impact of gender on leadership. Hence, like other large-N studies, we set out from several assumptions, the first being the assumption that the head of government singlehandedly decides the initial government COVID-19 responses in a country. The degree to which this assumption holds varies from country to country. Yet, it seems safe to assume that even in the cases where the head of government may not have the final say in terms of the exact strategies chosen, he or she will be in a profound position in terms of affecting the overall discourses which shape the political environment in which other actors choose these strategies. Future ‘second wave’ studies should study the initial COVID-19 government strategies decision-making procedures in detail to establish the gender of the decision-makers. Such ‘second wave’ studies may also explore gendered leadership through a longer period thus being able to determine the degree to which male or female decision-makers are likely to change their initial COVID-19 strategy throughout the pandemic.

Nonetheless, from a perspective that studies gender and comparative leadership, the initial period of the pandemic constitutes a very unique moment in contemporary time. First of all, all heads of government were confronted with the need to make a decision in extraordinary similar manners: though some did, of course, have the privilege of leading countries that were better equipped to meet the challenges posed by COVID-19 than others, or had the privilege of being hit later in the pandemic—and thus had more time to prepare their decision—the situation confronts all leaders in extraordinarily similar ways. Both in terms of the timing of the event, its severity, and the uncertainty in which leaders had to act.

Secondly, as recent research illustrates, it is especially in concern to political issues in which political parties have not yet settled their positions (so-called ‘uncrystallised issues’) that we see female political actors act in particularly gendered ways. Since decisions regarding how to act in the initial period of the pandemic were decisions on such uncrystallised issues, the possibility of finding gendered differences should be especially high. Hence, also from this perspective, does the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic constitute a unique opportunity to study gendered political behaviour as it looks before female political actors are influenced by their political party. However, with this in mind we should also be careful not to assume that the gendered differences we see in political leadership within the initial period of the pandemic do easily transfer to other political situations.

________________________

Note: the above research was funded by the Carlsberg Foundation.

Mette Marie Staehr Harder is Carlsberg postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Political Science at the University of Stockholm.

Mette Marie Staehr Harder is Carlsberg postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Political Science at the University of Stockholm.

Christoffer Bugge Harder is Carlsberg postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Biology at the University of Lund.

Christoffer Bugge Harder is Carlsberg postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Biology at the University of Lund.