Conventional wisdom amongst scholars, as well as much of the public, sees crime as an attractive and easy political issue for politicians seeking to expand their popularity. Regardless of whether crime is on the rise, mass publics are believed to be poor risk assessors, predisposed to react to perceived criminal behaviour with support for singularly punitive policies. However, drawing on her forthcoming book The Myth of Mob Rule: Violent Crime and Democratic Politics, Lisa Miller challenges this view, arguing the public perception of crime is close to reality, and politicians are often acting responsively, not opportunistically, to these trends.

Conventional wisdom amongst scholars, as well as much of the public, sees crime as an attractive and easy political issue for politicians seeking to expand their popularity. Regardless of whether crime is on the rise, mass publics are believed to be poor risk assessors, predisposed to react to perceived criminal behaviour with support for singularly punitive policies. However, drawing on her forthcoming book The Myth of Mob Rule: Violent Crime and Democratic Politics, Lisa Miller challenges this view, arguing the public perception of crime is close to reality, and politicians are often acting responsively, not opportunistically, to these trends.

In the UK, perhaps the most common illustration of the populist view on crime is Tony Blair and New Labour, which brought crime to the fore of the political agenda in Britain in the 1990s and early 2000s, despite rates of crime which had largely stabilized and had even begun to fall. This strategy, in the view of many scholars, was effective because the public is essentially the proverbial mob, la bella multorum captitum, largely incapable of knowing real material risk, and will flock to the political leader offering the most popular response to crime.

My research on crime as a political issue across three countries and many decades challenges this view (US, England and Wales, and the Netherlands). Rather, I find that public and political concern about crime rise and fall in surprisingly close tandem with real rates of serious violence, especially murder. After all, security from violence is an essential public good, and persistent exposure to growing risk of such violence is a first-order political problem that citizens are likely to notice and to expect the state to address.

In Britain, serious violence began a slow but steady increase in the early 1960s that did not peak until the turn of the 21st century. Not only was violent crime increasing, but murder rates nearly tripled, from a post-war low of roughly 0.6 per 100,000 persons to more than 1.5 per 100,000 in the early 2000s. This rising violence over just several decades was accompanied by prison riots, racial uprisings and the horrific murder of two-year old James Bulger in 1993. These events were rare but they served as illustrations of changes in everyday risk. Moreover, as rates of lethal violence increased in the democratized West in the second half of the twentieth century, rates of mortality from other causes were declining. In other words, as democratic societies were becoming more generally secure in the post-war period, acts of serious and deadly violence were on the rise.

Despite this, neither major political party in Britain increased attention to crime in any but the most marginal way during the first twenty-five years of the crime wave. In fact, it is widely accepted, and my research confirms, that there was a cross-party post-War political consensus on criminal justice which mean that, by and large, crime would be kept out of the public domain and addressed through low imprisonment, community sanctions, and offender reintegration. As this consensus broke down, the Conservatives were quicker on the issue than Labour – perhaps because crime and security issues are more typically “owned” by right-wing parties than left-wing ones. But even Conservatives spent very little time on criminal violence in party manifestos or Annual Speeches well into the 1990s, despite more than two decades of rising violence. It was not until John Major’s government that either party made crime a substantial political issue. By 1996, the Major government spent more than twice as much space in the Annual Speech addressing crime as any of the years during which Thatcher was in power.

Labour, for its part, gradually drew crime into its orbit but largely recycled the same policy proposals for decades, which primarily involved improving policing, situational crime prevention, and addressing the inequality and disadvantage that lead to crime in the first place. Not until 1997 did the party propose substantial reforms to the criminal justice system and to increase penalties on lawbreakers.

It is true that rates of serious violence in England and Wales peaked around the turn of the 21st century, so much of the Blair rhetoric comes long after the steepest increases and after violence levelled off. Many see this as evidence that New Labour prioritized crime in an opportunistic attempt to capture public attention to an issue that the public is easily drawn to, regardless of real risk, and to provide them with the vengeful policy responses they want.

But seen through the lens of the relative quiescence of the Labour party on the realities of crime for the previous thirty years, while both violence and public concern about it were rising, New Labour’s emphasis on crime looks less opportunistic and more like democratic responsiveness. This is all the more so because many traditional Labour voters are in precisely the low-income communities where risk of violence is greatest. While my research demonstrates that the public is willing to support policies beyond just increasing punishment when serious crime is on the rise – such as drug rehabilitation, early childhood education, educational opportunity and so on – there is also a sense that government must address the issue with some urgency. The prospect of reducing violence a decade down the road through programs aimed at tackling inequality are fine, but that does not help people reduce their exposure to risk in the here and now.

It may well be, given widespread disagreement about the causes of crime, that no action by the government can bring a halt, in the immediate future, to a rapidly rising shift in violence. More and tougher custodial sentences may have no impact on crime (though there is some evidence that it does, at least modestly), and may serve only, as legal scholar Michael Tonry has put it, to “further marginalize the marginalized.”

But making no effort to directly and immediately confront the growing risk that people actually experience also marginalizes the marginalized because of the damage – both individually and collectively – that growing violence inflicts. Seen in this way, the political competition over crime, that began slowly in the 1970s and culminated with Tony Blair and Home Secretary Jack Straw’s famous re-positioning on the issue, is a democratic corrective to the insulation of elites who had largely neglected rising rates of violence, particularly with respect to the use of state criminal justice apparatus in response.

If my research reveals anything practical about the politics of crime and punishment, it is that public anxiety about crime is usually in response to changes in serious violence and when political parties and other elites do not respond, the public is likely to take notice. It is reasonable for the public to expect that their concerns about such a basic material condition will be prioritized by their representatives. Left-wing parties, in particular, ignore crime and safety at their peril, not only because they are less often seen as the party that prioritizes security, but also because violent crime is not randomly distributed throughout the population. It disproportionately affects people situated in the demographic that left parties have traditionally tried to attract.

Being governed by “mob rule” is not as risky as it sounds. Indeed, if you live in a dangerous neighbourhood, it may serve you better than government by elites.

___

About the Author

Lisa L. Miller is on the faculty of political science at Rutgers University and is the 2015-16 John G. Winant Visiting Professor of American Government at the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford . She is the author of the forthcoming book, The Myth of Mob Rule: Violent Crime and Democratic Politics (Oxford University Press, 2016), as well as The Perils of Federalism: Race, Poverty and the Politics of Crime Control (OUP, 2008). In February she is presenting the findings of this work at the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford.

Lisa L. Miller is on the faculty of political science at Rutgers University and is the 2015-16 John G. Winant Visiting Professor of American Government at the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford . She is the author of the forthcoming book, The Myth of Mob Rule: Violent Crime and Democratic Politics (Oxford University Press, 2016), as well as The Perils of Federalism: Race, Poverty and the Politics of Crime Control (OUP, 2008). In February she is presenting the findings of this work at the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford.

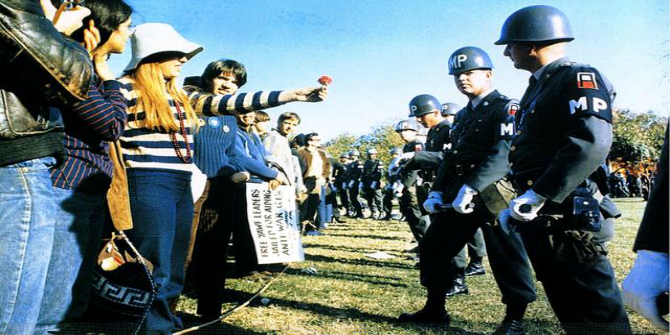

(Featured image: Ronnie MacDonald CC BY 2.0)