Will David Cameron’s reshuffle pay off with the electorate? While we can interpret the changes as an electoral gambit, Mark Garnett argues that there might be a deeper purpose. Alongside the prime minister’s old reluctance to alienate old friends, this reshuffle suggests a keen (if not desperate) desire to cultivate some new ones.

Will David Cameron’s reshuffle pay off with the electorate? While we can interpret the changes as an electoral gambit, Mark Garnett argues that there might be a deeper purpose. Alongside the prime minister’s old reluctance to alienate old friends, this reshuffle suggests a keen (if not desperate) desire to cultivate some new ones.

Most aficionados of British political history know the piece of advice attributed to William Gladstone – that a successful prime minister must be ‘a good butcher’. In other words, prime ministers should possess the steely resolve necessary to dismiss colleagues who are no longer ‘fit for purpose’ – whatever that purpose might be. Long and distinguished service, or close personal friendship, might be noted in the subsequent exchange of letters; but they should never be allowed to affect the decision itself.

Until July 2014, allies and enemies would have agreed that David Cameron’s butchery fell short of Gladstonian standards. Indeed, his attitude to ministerial reshuffles seemed to be the only remnant of his once-vaunted ‘Compassionate Conservatism’. Even when colleagues lost important jobs, they somehow contrived to cling on to cabinet rank in some ill-defined capacity. On other occasions, Cameron seemed willing to stretch the terms of the ministerial code in order to spare himself the pain of parting.

The reshuffle has dissipated these impressions. In a frenzied assault on all ministerial ranks, the prime minister has taken on a new guise, as Cameron the Barbarian. Long-standing confidants like William Hague and Michael Gove have been spared the unkindest cut, but even they have been deposited in the departure lounge. Others have been liquidated in a fashion that would have induced respectful murmurs from Vlad the Impaler.

So Cameron has a ruthless streak after all. But is he a good butcher, showing sound judgement as well as brutality? The obvious point of reference, for a reshuffle on this scale, is Harold Macmillan’s ‘Night of the Long Knives’ of July 1962. On that occasion, seven full cabinet ministers were sacked, compared to just three departures in 2014 (and one of those, Gove, is still entitled to attend cabinet meetings as Conservative chief whip). But in both cases the overall extent of change is reminiscent of a Soviet-style purge.

Superficially, at least, the resemblance between the two cases extends to motivation. By 1962 Macmillan was aware that his ministers had become unrepresentative of a rapidly-changing society; and the same realisation seems to have prompted Cameron. Macmillan was also driven by tactical considerations – he doubted that his existing team could win the next election, and he was probably right. He also knew that, in the new television age, policy presentation was increasingly important. As a result, the cabinet appointees of 1962 were considerably younger than their predecessors. But Macmillan had always been interested in ideas; and after his reshuffle the cabinet (including such luminaries as Sir Keith Joseph) was undoubtedly refreshed in terms of creative thinking.

By contrast, David Cameron seems to have conducted his reshuffle with the intention of expelling, rather than embracing, creative thinkers. Michael Gove – for good or ill, the government’s nearest approximation to Sir Keith Joseph – has lost his departmental responsibilities, while David ‘Two Brains’ Willetts is no longer a minister. Even without the pre-reshuffle hype about redressing the gender imbalance in ministerial ranks, observers of British politics would have been tempted to interpret the changes in terms of style rather than of policy substance. The new female ministers might owe their elevation purely to intellectual and/or administrative merit, rather than a cynical desire to lend the Conservative front bench a veneer of social ‘normality’. However, thanks to the government’s threadbare legislative programme in the last year of the parliament they will have little chance to prove their mettle before the election. If the merits of these individuals were too obscure to be recognised by the prime minister in 2013 or even 2012, why were they suddenly revealed unto him when he sensed an approaching election?

If Cameron’s reshuffle was nothing more than an electoral gambit, even hardened students of British politics would be entitled to sense a new low in the use of the dark arts. However, there is an alternative explanation, in which the focus on social representation turns out to be little more than a smokescreen for a deeper purpose.

On current trends, perverse electoral arithmetic suggests that the Conservatives might win a plurality of votes at the next election, without being able to form part of a new government. In such circumstances, David Cameron will need reliable friends in order to survive as Conservative leader. This reshuffle is different because, alongside the old reluctance to alienate old friends, it suggests a keen (if not desperate) desire to cultivate some new ones. In hindsight, the verdict on David Cameron might be that he lacked the butchery skills demanded of a successful prime minister, but he could wield the knife with unexpected panache when he wanted to consolidate a loyal phalanx of supporters in preparation for his party’s next spell in opposition.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

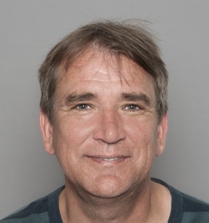

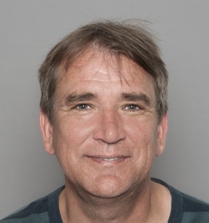

Mark Garnett is Senior Lecturer at Lancaster University. His research is chiefly concerned with UK Politics, with particular reference to the relationship between ideas and practice; the Conservative Party; and think tanks. He is author, with Professor David Denver, of a study of British general elections since 1964 (Oxford University Press).

Mark Garnett is Senior Lecturer at Lancaster University. His research is chiefly concerned with UK Politics, with particular reference to the relationship between ideas and practice; the Conservative Party; and think tanks. He is author, with Professor David Denver, of a study of British general elections since 1964 (Oxford University Press).

No he has just acted in a gender discriminatory manner, in a poor attempt to woo women voters, by appointing some women to the cabinet. Just like his sudden hard stance on the European court of human rights which he has no chance of delivering any alterations, it’s electioneering pure and simple and will be forgotten once the election is over and done with.

Real leadership dictated that the political system needed to be changed in order to reflect a democratic process that holds politicians/MPs accountable to those who they are meant to be representing. Instead, we see a reshuffle of individuals – with the emphasise of getting more women into positions – but a WEAK system that continues to be in desperate need of change.

The problem for democracy is that opposition leaders are too WEAK to confront such fundamental changes. Thus, an undemocratic system lives.

Who is meant to be representing the ‘people’ – when MPs continue to have No Legal or Statutory Obligation to Represent anybody..???

Can we really rely on the news media to harness the voices of the public in cases where political failings on ‘ordinary’ people have been rife? I don’t think so!