Since the onset of the Great Recession, obtaining finance has been major barrier for innovating firms. This is because, on top of the costs arising from ‘asymmetric information’, knowledge-based businesses also face another barrier in accessing finance, that is, the intangibility of assets being financed. A new report by Hiba Sameen and Gareth Quested examines the link between firm innovation and growth and argues that a wide range of financial instruments need to be made available to them.

Since the onset of the Great Recession, obtaining finance has been major barrier for innovating firms. This is because, on top of the costs arising from ‘asymmetric information’, knowledge-based businesses also face another barrier in accessing finance, that is, the intangibility of assets being financed. A new report by Hiba Sameen and Gareth Quested examines the link between firm innovation and growth and argues that a wide range of financial instruments need to be made available to them.

Innovation is widely considered to be a primary source of long-term economic growth, and policies to encourage firm-level innovation are high on the agenda in most countries. However, research previously published by the Big Innovation Centre revealed that obtaining finance was a major barrier for innovating firms: 57% of innovative firms faced difficultly in accessing finance in 2012 up from 38% in 2007/8. Our results also revealed that being an innovator made it much more likely a firm would face difficulties obtaining finance.

New research published last week by the Big Innovation Centre establishes the link between innovation and growth and studies how firms finance their innovative activities using firm level financial data. We identify systemic barriers faced by innovative firms in accessing finance and knowledge gaps in finance that are preventing funding from getting to these high growth businesses.

In economic theory, the reason for these difficulties typically stems from the fact that those who create and manage firms (entrepreneurs) are usually not the same individuals as those who have the means to finance this activity. This implies that an information gap is likely to exist between those asking for funds and those supplying them. Economists refer to the extra costs thus induced as problems arising from “asymmetric information” and resulting in raising the costs of obtaining finance from sources external to the firm. Athough this will be true to some extent for all firms, the problem is particularly salient in the case of new firms and firms undertaking innovative activities.

However, knowledge-based businesses also face another barrier in accessing finance, that is, the intangibility of assets being financed. Such intangible capital typically has relatively low salvage value because it is also idiosyncratic – for example, the fact that the firm owning the capital goes out of business is a signal that its value was low. Thus the financing of innovation typically has higher bankruptcy and dilution costs for the financier than non-innovative activities. In addition, there is currently little or no market for distressed intangible assets. The human capital involved goes with the employee, and usually they will capture any residual value from that in the form of wages in future employment. Despite this, most of the knowledge generated by employees is often codified into the firm, such as with the creation of copyright whereby the knowledge becomes a business asset. When external financiers do not acknowledge this, it leads to the firm being undervalued. And thus debt instruments that are secured by the value of the capital asset are not likely to provide a useful source of funding for innovation.

Our new report studies the relationship between innovation and growth, and how firms finance growth through innovation using firm-level time-series balance sheet data of over 20,000 firms for 12-15 years that have had an external equity investment deal since 1998.

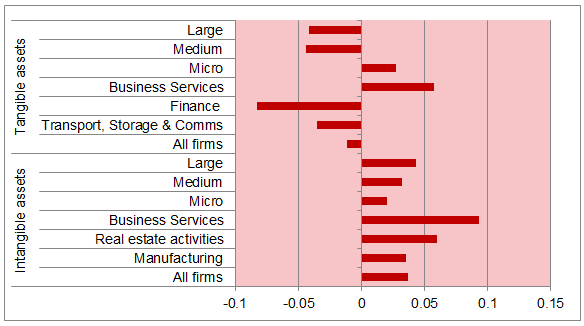

First, we establish the relationship between innovation and growth. To do so, we run a logistic regression estimating the impact of intangible assets on the probability of the firm being high growth or not, controlling for firm size, industry and the age of the firm. Our results, as seen Figure 1 below, indicate that firms with higher levels of intangible assets as a proportion of total assets are more likely to be high growth firms; specifically, doubling the intangible asset ratio increases the probability of being high growth by 3.6%. This effect is much larger for firms in some sectors – for firms in the Business Services sector a doubling the intangible asset ratio increases the probability of being high growth by 9.8%. This suggests that a relationship exists between the intangible asset ratio and whether a firm is high growth or not. There may be some reverse causality here too, however – it may also be that as firms grow they tend to invest more in intangible assets.

Figure 1: Regression coefficients for probability of being a high-growth firm

Note: Bars represent marginal effects from logistic regression. Only significant coefficients reported. Negative coefficients indicate firms’ reduction in probability of being high growth and positive marginal effects indicate an increase.

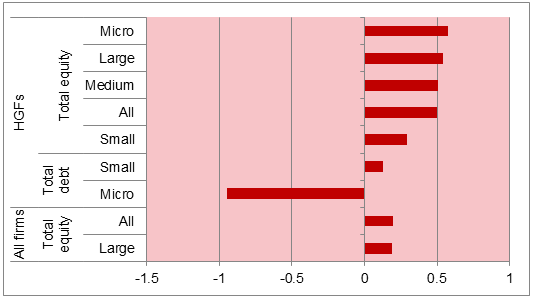

Next, we study how firms finance their innovative activities. Our econometric model looks at how a change in total debt and a change in total equity are associated with a change in intangible assets for a particular firm.

The results in Figure 2 show that firms tend to finance their intangible assets through increased equity as opposed to debt. For high growth firms (HGFs) this effect is even stronger – HGFs finance a higher proportion of their intangible assets through equity. For every £1m increase in equity, HGFs invest a further £499,000 in intangible assets, compared to just £195,000 among all firms. Micro firms tend to reduce their level of total debt – an increase in intangible assets is associated with a reduction in the accumulation of debt. Small firms finance some part of their intangible assets through debt, although they finance more through equity. However, medium and large sized firms finance their increase in intangible assets largely through increased equity. This result, to some extent, reflects the availability of different sources of finance across the funding escalator. For example, small firms and young firms will have few sources of equity available to them to finance their intangible assets, and thus have to rely on debt. Large firms have more diverse credit profiles, as their size allows for flexibility in their approach.

Figure: 2 Regression coefficients for financing of intangibles by debt or equity

Note: Bars represent fixed effects GLS regression coefficients. Only significant coefficients reported. Negative coefficients indicate firms reduce investment in intangible assets for an increase in debt or equity; positive coefficient shows an increase in investment in intangibles.

Overall, our results indicate that firms are much more likely to finance their intangible assets through equity rather than debt; for high growth firms this effect is much stronger. This is due to the fact that equity is much better at valuing intangible assets and innovative business models compared to debt.

However, small high growth firms are still reliant, to some extent, on debt to finance intangible assets which reflects the importance of debt finance. For small firms, it is important to also have a wide range of financial instruments, including debt, available to them to finance innovation as selling equity too early on in their growth trajectory may hamper their growth instead of building their vision.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Hiba Sameen is a researcher at the Big Innovation Centre, an initiative of The Work Foundation and Lancaster University.

Gareth Quested is a research assistant at the Big Innovation Centre, having joined in January 2012. He has a BA (Hons) in Economics and Politics from the University of Exeter and is currently studying part-time for an MSc in Economics from Birkbeck College.