James Strong investigates whether the greater prominence given to individual military casualties in recent years made the British public more sceptical about military action in general. He finds that prominent coverage of military casualties causes the public to pay greater attention to military campaigns, but does not necessarily shape public attitudes towards those campaigns.

James Strong investigates whether the greater prominence given to individual military casualties in recent years made the British public more sceptical about military action in general. He finds that prominent coverage of military casualties causes the public to pay greater attention to military campaigns, but does not necessarily shape public attitudes towards those campaigns.

An MoD study from 2012, obtained by The Guardian, suggests the prominence given in media coverage to British military fatalities from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan over recent years has led to an inaccurate public perception of the actual risks involved in using military force overseas. Accepting the premise that public support is important for any military action, the report suggests a number of communication policy steps that might help counteract trends seen during recent conflicts. It acknowledges the particular problem with the Iraq and (fourth) Afghan wars, as well as with the vetoed Syria intervention – that the public saw no clear national interest in involvement – while also suggesting ways to frame the risk of military casualties as “knowingly and willingly undertaken as a matter of professional judgement”.

The paper is quite sensible in many regards, though newspaper coverage in the Guardian and Daily Mail (technically the same coverage, as the Mail’s story is based entirely on the Guardian’s exclusive) focuses on the “disgraceful” suggestion (and it is just a suggestion) that repatriation ceremonies should take on a lower profile. It does warn against creating a “Praetorian Guard” culture, with the armed forces cut off from society, while also arguing that military service needs to be seen as more than just another job given the particular risks involved. It also makes a number of more ‘blue skies’ suggestions, including placing a greater emphasis on using drones, special forces, mercenaries and soldiers from allied states with higher levels of public tolerance to casualties in future operations.

How viable is all this? I think there are two distinct questions here:

1) Has the greater prominence given to individual military casualties in recent years made the British public more sceptical about military action in general?

2) What impact would there have been on public perceptions of the war in Afghanistan had repatriations been given a lower profile?

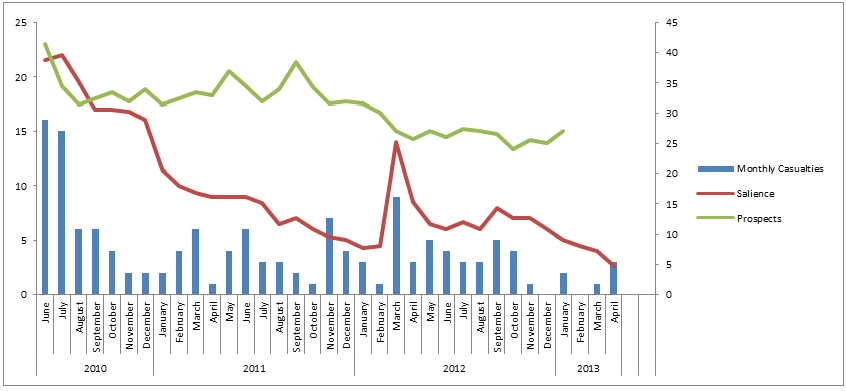

To answer 1), I looked at casualty levels and YouGov opinion polls since mid-2010. Before this date (and this is significant in itself) relatively few polls were conducted asking either how significant individuals considered the war in Afghanistan to be, or what prospects respondents saw for its successful conclusion.

Figure 1 shows monthly military combat fatalities, the average salience ascribed by poll respondents to Afghanistan as a national political issue, and poll respondents’ estimates of the prospects for military victory in the Fourth Afghan War. It appears to show a relationship between casualties and issue salience, with a pattern of general decline in both interrupted by a large jump in March 2012 following the deaths of six servicemen in one day, an event that prompted widespread media coverage because this was the joint largest one-day combat fatality count of the entire operation. What it does not appear to show is a relationship between prominent casualties and declining public faith in the likelihood of ultimate victory. That faith does decline slightly, but only slightly. The March 2012 shock does not register at all.

Figure 1 suggests that prominent coverage of military casualties causes the public to pay greater attention to military campaigns, but does not necessarily shape public attitudes towards those campaigns. The wide literature on public opinion as an influence on foreign policy predicts such a finding; while casualty levels are not irrelevant, they have a relative rather than absolute effect on public attitudes. Democratic publics are generally willing to tolerate military fatalities incurred as part of campaigns seen as necessary, legitimate, and successful. The two elements are not independent; both the number and manner of individual deaths can shift views on any of these factors. But death alone does not change how the public views a military campaign. The public understands that military action implies military casualties.

To answer 2) I pose a counterfactual. What if RAF Brize Norton had never been closed for refurbishments in 2007, forcing vehicles carrying the repatriated remains of deceased service personnel from Iraq and Afghanistan to travel through the town of Wootton Bassett on their way to the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford? What if the poignant images of a small town brought to a standstill in tribute to 345 fallen men and women had never been relayed across British television screens and reported prominently in British newspapers? Would that have lowered the place of military casualties in the public’s calculations about the Afghan conflict?

I don’t think so. I don’t think so for two reasons. Firstly, the public was growing gradually less sure about Afghanistan before 2007. Wootton Bassett did not cause the British military to experience rapidly rising casualty rates after June 2006, the decision to attempt to pacify Helmand province did that. Nor did it contribute to the immense difficulty Britain will still have in achieving anything that can be labelled victory in Afghanistan’s lawless hinterlands. Secondly, however, I think it is worth noting also the difference that Wootton Bassett made in disaggregating British public attitudes towards the armed forces from those towards specific military campaigns. Before Wootton Bassett uniformed service personnel were personally abused in the streets around military bases. But the simple acts of remembrance enacted, if not spontaneously, then at least without state direction in this small Wiltshire town caught the public imagination. By recognising the fallen of the Afghan war, Wootton Bassett helped the public more generally to treat individual soldiers as heroes, even while disagreeing with the specifics of their present mission.

This is crucial. Historically, public attitudes towards service personnel have varied according to how a particular campaign is perceived. The dead of successful, legitimate, or necessary campaigns are lionised while those of unsuccessful, illegitimate, or unnecessary wars are pitied. The contrast between how the US public treated Vietnam veterans compared to their World War Two predecessors is the usual example given. Yet Wootton Bassett made heroes of the Afghan war’s dead, regardless of the public’s scepticism about the campaign. This then fed back into public perceptions about the action as a whole. The dead of unsuccessful, illegitimate, or unnecessary wars are victims (usually of politicians’ incompetence), the dead of the Afghan war are heroes, therefore it cannot be an unsuccessful, illegitimate, or unnecessary war.

Wootton Bassett alone cannot save public attitudes towards Afghanistan. The war has gone on too long, the goals are too diffuse, and the casualties too high. There will be no moment of victory, only a moment of weary withdrawal. But the suggestion that the prominent coverage given to repatriations undermined the public’s willingness to stay the course deserves careful consideration. I haven’t proved it, here, but I suspect, as I have set out, that the dynamic was more complicated than that.

This article was originally published on James Strong’s blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr James Strong is a Fellow in the Department of International Relations at the LSE. He blogs at http://drjamesstrong.wordpress.com/ and tweets from @Dr_James_Strong.