Economic and cultural factors are often presented as alternative explanations of Brexit. Miguel Carreras, Yasemin Irepoglu Carreras, and Shaun Bowler explain why both actually matter and how they are related to each other.

Economic and cultural factors are often presented as alternative explanations of Brexit. Miguel Carreras, Yasemin Irepoglu Carreras, and Shaun Bowler explain why both actually matter and how they are related to each other.

Recent political developments in advanced democracies have generated a scholarly debate on what led to these results. While some scholars argue that economic grievances among the “losers of globalization” are at the root of these political changes, other works suggest that recent political developments result from a cultural backlash against immigrants and internationalism.

Previous research often presents economic and cultural factors as alternative and separate explanations of support for Brexit. Studies that focus on the individual level conclude that cultural values serve as better predictors of the Brexit support than economic variables. Yet, analyses of the Brexit vote using electoral data at the local level have shown that the level of unemployment, housing prices, and exposure to economic shocks related to globalization are all strong predictors of the share of support for “Leave” in the referendum.

In our recent paper we show that both factors mattered for the Brexit vote and that they are related to each other. We argue that much of the economy vs. cultural values debate has been misguided by not taking into account how localized economic decline may influence value orientation. We argue that geographically concentrated economic distress is related to cultural backlash in Britain for three reasons.

First, individuals who live in areas suffering a long-term economic decline are more likely to perceive immigrants as an economic threat. Structural economic problems lead to a heightened sense of economic insecurity. Previous research shows that people who live in economically depressed areas might perceive foreign workers as a threat to their chances in the labour market or to the continued supply of welfare benefits. Another study has similarly documented that anti-immigration and Eurosceptic views have increased in economically depressed areas, between 1997 and 2015.

Second, regardless of personal economic hardships, the perception that the economy is in a downward trajectory can lead to nativist sentiments and hostility towards outsiders. Previous research suggests that evaluations of the national economy have a stronger impact on immigration attitudes than personal economic circumstances; and we know that local economic conditions strongly influence citizens’ evaluations of the national economy. In sum, pessimism regarding the economic trajectory of the country might lead people to scapegoat immigrants and develop more nativist views.

Third, the information environment and elite rhetoric also plays a key role in shaping mass attitudes toward immigration and cultural grievances more generally. In the UK context, UKIP broadened its appeal (starting around 2010) by combining its hard Euroscepticism with a clear message of firm opposition to immigration. A recent book on the rise of UKIP reveals that in the past decade immigrants have been presented by this party as a threat to British national identity and to the economic wellbeing of workers in Britain. UKIP leaders recognized the potential of targeting disenchanted, working-class, and poorly educated voters.

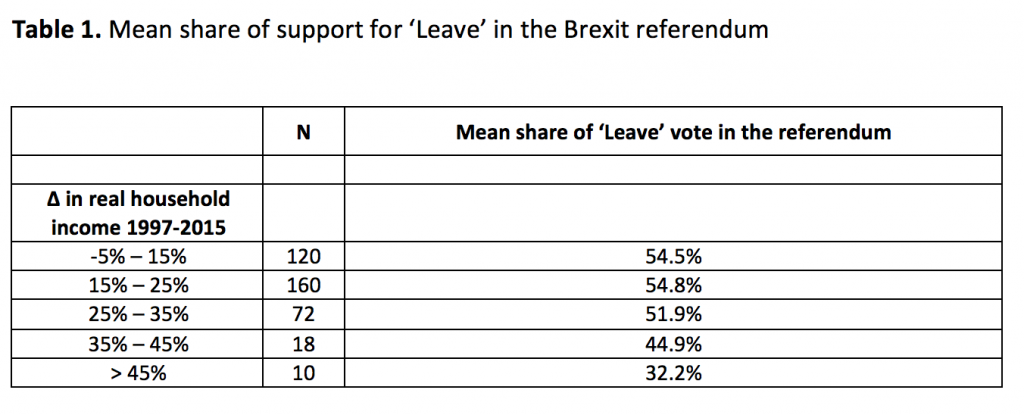

Descriptive statistics show that support for Brexit in the referendum was much higher in districts that have suffered long-term economic distress. Table 1 below presents the average share of support for ‘Leave’ in the referendum for different levels of long-term economic performance at the local level.

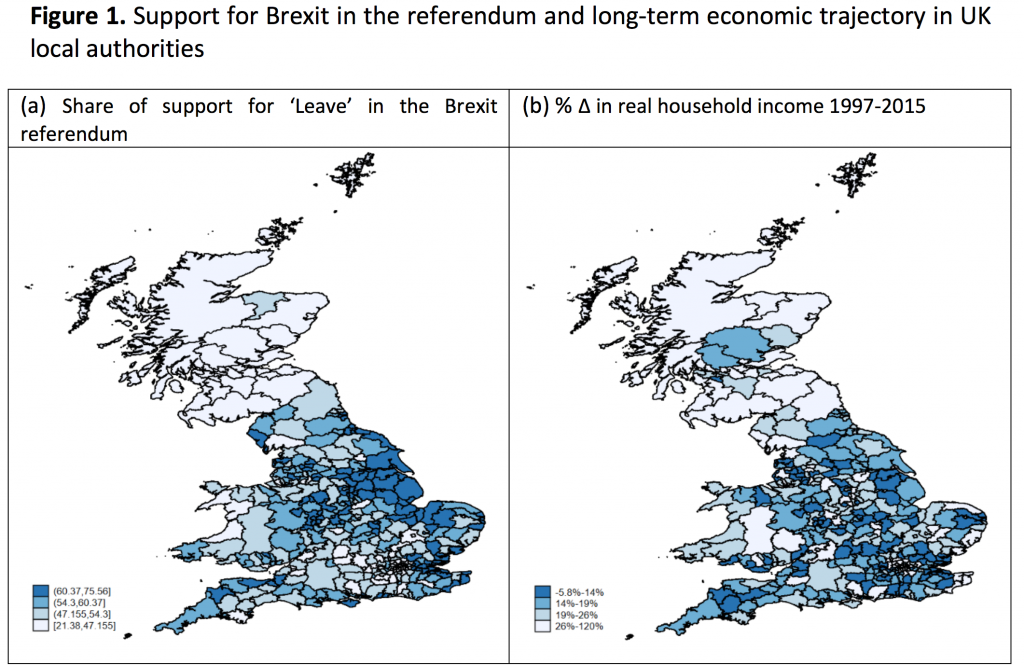

The association between long-term economic performance and support for Brexit can also be seen in Figure 1, which presents a map showing the share of support for Brexit in the referendum (panel a) and a map showing the change in real household income between 1997 and 2015 (panel b). The maps again suggest that support for Brexit is higher (darker shades in panel a) in areas where the local economy is in a downward trajectory (lighter shades in panel b).

We then estimated a series of multilevel models to assess whether economic decline shapes support for Brexit using economic, sociodemographic, and electoral data from 380 districts in the UK, which were obtained from the Office for National Statistics.

Our multilevel regressions confirm our expectation that short-term changes in household income before the referendum are not related with support for Brexit. However, long-term economic decline (10- or 18-year changes in real household income at the local level) is associated with higher support for Leave in the referendum. The results are therefore consistent with accounts of Brexit that emphasize the importance of the long-term stagnation or decline of real incomes in de-industrializing areas of the United Kingdom.

Exploring the causal mechanism: does economic decline affect political attitudes?

Our main goal in this research project was to investigate whether cultural grievances (i.e. anti-immigration attitudes, Euroscepticism, nativism) are a plausible causal mechanism linking long-term economic decline and support for Brexit. In order to test this hypothesis, we estimated a causal mediation analysis.

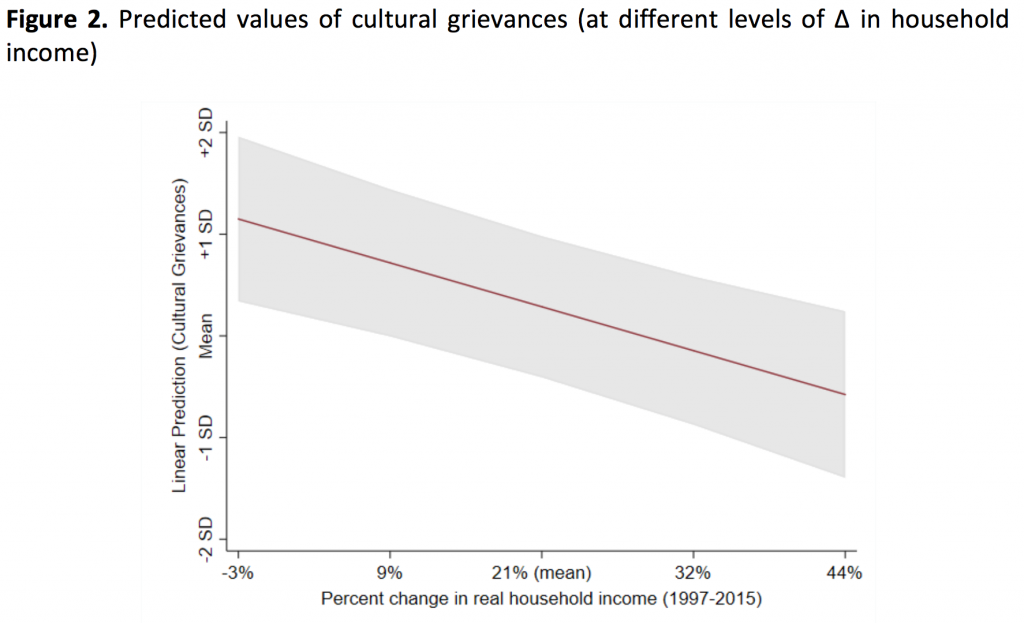

Our results suggest that cultural backlash is a causal mechanism that can account for much of the correlation between economic decline and support for Brexit. In this mediation analysis, we used information from the British Election Study 2014-2017 Internet panel to create an average “cultural grievances” score for each district in the United Kingdom. Our results show that anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic attitudes are likely to be higher in economically depressed areas. These cultural grievances are, in turn, significantly connected to the share of support for Brexit in the referendum.

The mediation analysis reveals large indirect effects with as much as 64% of the effect of long-term change in real household income being mediated through cultural grievances, and 50% of the effect of long-term changes in unemployment being mediated through cultural grievances. The figure below shows the predicted values of our summary indicator of “cultural grievances” at different values of long-term change in household income.

The findings of this article contribute to our understanding of electoral politics in the current period. Studies that emphasize that voters who hold nativist, anti-immigrant, and ethnocentric views are to blame for the rise of populist and nationalist political movements can generate complacency among the liberal democratic establishment.

However, our study shows that this cultural backlash is a result of long-term inequalities in economic performance between areas benefiting from structural economic changes (e.g., globalization and automation) and regions engulfed in a long-term economic decline. Our analysis suggests that addressing the roots of this discontent and adopting targeted economic policies that help the regions (and citizens) left behind by economic changes is essential if liberal democratic forces want to limit the rise of nationalist and populist politicians.

______________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in Comparative Political Studies.

Miguel Carreras is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Riverside.

Miguel Carreras is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Riverside.

Yasemin Irepoglu Carreras is Assistant Professor of Teaching, Political Science at the University of California, Riverside.

Yasemin Irepoglu Carreras is Assistant Professor of Teaching, Political Science at the University of California, Riverside.

Shaun Bowler is Distinguished Professor & Dean of the Graduate Division at the University of California, Riverside.

Shaun Bowler is Distinguished Professor & Dean of the Graduate Division at the University of California, Riverside.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay/Public Domain.

Open borders and the unsustainability of the UK system within the EU system are factors which are predominantly interpreted by the liberal intelligensia as cultural concerns.

Open borders leads to import dependancies, loss of green infrastructure and increased population densities.