We hear it all the time in the media and in public debates about education – that parents have a right to do what is best for their own children when it comes to choosing schools. But research shows the British public might really think differently. Sonia Exley finds a surprisingly egalitarian attitude toward educational opportunities amongst British parents and non-parents alike.

We hear it all the time in the media and in public debates about education – that parents have a right to do what is best for their own children when it comes to choosing schools. But research shows the British public might really think differently. Sonia Exley finds a surprisingly egalitarian attitude toward educational opportunities amongst British parents and non-parents alike.

Recent research on public attitudes to school choice from the 2010 British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey reveals that more than two-thirds of those questioned support a basic right for parents to choose schools. Furthermore, seven in ten believe parents ought to ‘put their own child first’ when it comes to choosing schools.

Parents’ ‘right to choose’ the type of education their children receive is enshrined within the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and these days the idea that private schools (or even parental choice legislation in Britain – now a key element of state sector provision) should be abolished often sounds like some archaic flight of fancy from a previous, more leftist age. However, a key difficulty with parental choice rights is that they tend to impact on the lives of others and on the schooling system overall. Evidence from the BSA indicates that a majority (61 per cent) also think it is important for parents to ‘consider the needs and interests of other children’ when making schooling decisions.

Debates within political theory have often looked at the extent to which parents exercising ‘partiality’ towards their own children can be considered legitimate, given the unequal world in which we live. In ‘How Not to Be a Hypocrite’ Adam Swift argues that within Britain today it might be fair for parents to pass certain sorts of cultural advantage on to their children (for example by reading them bedtime stories). However, sending them to private or selective schools – where attendance at these schools has a major impact on life chances – is much more problematic. Similarly, in ‘School Choice and Social Justice’ Harry Brighouse argues that parental choice rights might exist in an education system where major inequalities between schools do not exist, but within the current British context they conflict unacceptably with principles of social justice.

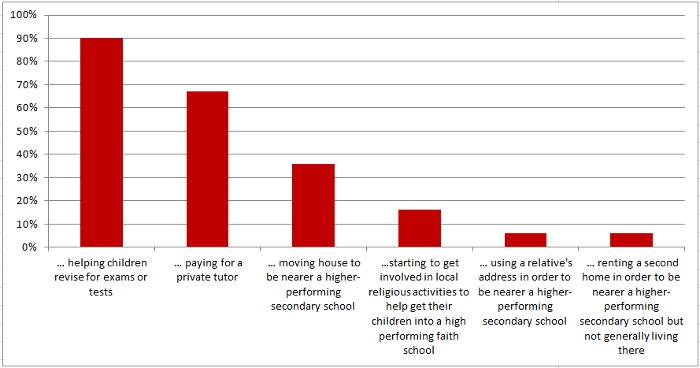

Probing further on attitudes towards ‘parental partiality’ within a school choice context, the BSA survey asked people for their views on a range of actions that parents may take in order to ensure places for their children at ‘good schools’ as we can see in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Approval of actions by parents to improve their child’s chances of accessing certain schools

– % who approve of …

Note: Base=2216

While most in Britain approve of parents helping children with schoolwork ‘in order to improve their chances of gaining a place at a particular school’ and a majority also supports parents paying a private tutor to do the same, seeking further competitive advantage than this appears to be where public support ends. A notable finding from the BSA survey is that only a minority (36 per cent) support people moving house in order be nearer ‘better schools’. Less honest or fraudulent actions by parents which often receive media attention such as becoming involved in religious activities purely in order to access faith schools or lying about one’s address when applying for schools are met with widespread disapproval.

Perhaps most importantly, while many may feel it is acceptable for parents to pay for a private tutor, this approval does not extend to parents paying for private schools. Only 38 per cent of people in Britain believe that parents who can afford it should be able to pay for better education. More than six in ten say that the quality of education should be the same for all children.

Are views different once you have kids of your own?

Do beliefs differ between parents and non-parents? Although those with children are more likely than those without to support a basic parental right to choose, they are no more likely than others to say that one’s own children should come first. In fact, BSA evidence indicates that the only group emerging as holding consistently more individualist views about school choice were those who had chosen to send one or more of their children to private school. This finding might reflect more right-wing attitudes among parents of the privately educated in general, though analysis did take into account where people stood on a ‘left- right’ continuum. What is more likely, then, is that parents who have paid fees for their children’s education tend to hold stronger views about parental rights, partly as a result of having made their own decision to ‘go private’.

Findings reported here are arguably quite contrary to what we might expect in the current British social and political climate. Given such a clear focus within Coalition Government policy on individual families’ right to choose, parental rights to set up schools and consumer freedom to pay for ‘the best’, lack of approval for parents seeking to gain competitive advantage for their own children over others is somewhat surprising.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

____________________________________

About the author

Sonia Exley- LSE Social Policy

Sonia Exley- LSE Social Policy

Dr Sonia Exley is a Lecturer in the LSE Department of Social Policy. Her recent research focuses on parental partiality, school choice, and educational equality.