Over the next four years, the share of national income devoted to the welfare state will fall significantly for the first time since 1945. Howard Glennerster examines this fall and what it will mean for UK citizens over the long term.

Over the next four years, the share of national income devoted to the welfare state will fall significantly for the first time since 1945. Howard Glennerster examines this fall and what it will mean for UK citizens over the long term.

There are many questions that can be asked about the cuts the coalition government announced in October. Were they necessary to reassure the bond markets? What impact will they have on jobs and the economic recovery? But I am neither a macro-economist nor an expert on bond markets. I am asking a different set of questions. How significant are the cuts for the social welfare system? Who will gain and lose? What are the long-term implications for the welfare state?

How large are the cuts comparatively?

The coalition government’s 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review represents the largest sustained fall in public expenditure since 1922.

The cuts required by the IMF in 1976 produced a fall in real public spending of 4 per cent followed by a return to the previous level of spending two years later. Cuts in social programmes after the Suez crisis and the Korean War did not reach even that scale. After the 1931 crisis, real spending once more fell by about 4 per cent for two years and then grew again. From 1921-24 government spending, central and local, fell by over 8 per cent – the “Geddes Axe” as it was called, after the chairman of the committee that recommended the cuts.

How far real spending will fall this time depends on the rate of inflation and to what extent the government holds its nerve in keeping to its cash limits. But assuming it does, estimates from the Office of Budget Responsibility suggest that from the end of 2010 to the end of 2015 there will be a fall in current spending (staff and year-on-year expenses) of 7.4 per cent. Government investment (on buildings) will fall, on their figures, by 20 per cent up to 2014 (only to rebound to its present level during what is likely to be a pre-election year, 2014-15). Social security spending will fall in real terms by 0.4 per cent a year; this arises partly from choosing a lower price index to set benefit rates, partly because unemployment will ultimately fall, and because more people will be pushed back into work through welfare reform and child benefit changes. If growth goes according to forecast, we shall see a reduction in the share public spending takes of GDP from 47 per cent in 2010 to 39 per cent in 2015.

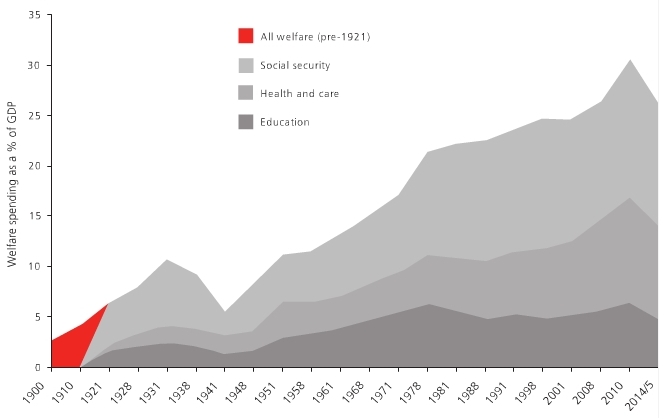

So these are very big reductions on any historical comparison. One has to remember that in the 1920s and 1930s governments did not raise spending sharply in recessions and so have to adjust afterwards. Even so, for the first time since 1945, the share of the national income devoted to the welfare state will fall significantly in the next four years. It had risen sharply as a result of the Blair and Brown governments and the recession. The welfare budget as a share of GDP will probably fall back to a little above what the Blair government inherited in 1997 – 26 per cent compared to the 25 per cent it was in 1996, as the Figure below shows.

Welfare spending as a percentage of GDP across policy areas, 1900-2015

Who will the cuts affect?

So where does all this leave us or, more to the point, where does it leave the most vulnerable? Here it is difficult to improve on the judgement of the Institute for Fiscal Studies that despite some headline-grabbing moves to cut some benefits for the better off, the major immediate impact is going to fall on poorer younger families, notably those in the bottom 40 per cent of income distribution. They depend most on public services. School spending is to rise by 0.1 per cent a year in real terms and hence is “protected”, but school populations are rising by 0.7 per cent a year so this amounts to real year-on-year cuts per pupil.

The effect is going to be considerable in the case of services for older people. Real spending on the NHS is planned to rise by 0.1 per cent a year but the impact of ageing on health care means that the NHS needs an extra 1 per cent a year just to stand still. Local authority grants are to fall by more than a quarter and despite small extra funds for social care this is going to have a large impact on services for older people and children in need of care and support. Just how much will depend on what councils do to raise more revenue. I assume they will find that difficult in the coming economic and political climate.

How long term is the problem?

These immediate issues, however, mask a longer-term problem. Between 1986 and 2008 the share of the GDP going to pay for the welfare state grew by 5 per cent. Yet national revenue fell as a share of national income. Britain’s social policy ambitions outran the electorate’s willingness to pay for them. Or, more accurately, outran politicians’ willingness to ask them.

Nor will this problem go away. In work I did for the Royal Society of Arts 2020 Commission, I showed that simply to sustain existing service and benefit levels and fulfil promises made by all parties we would need to spend 4 per cent more of our GDP on social welfare by 2030 and 8 per cent more by 2060. We are becoming an older population with all that means for demands on public spending. That figure would be even more if free personal care for the elderly, as in Scotland, were added to the menu. None of that looks in prospect. But private alternatives are not that easy to see either.

Why is private insurance not the answer?

Doom-mongers have forecast the end of welfare states before. It has not happened. One reason is that all the features that make it difficult for governments to sustain benefit levels pose even more problems for the private insurance sector. The chances of living longer are rising steadily. Hence, so are the actuarial costs of private pension schemes. Employers are cutting back on occupational pension schemes and leaving the financial risks of old age to individuals. For economic reasons we now understand much better than we used to why individuals put off taking pension decisions. The same is true for long-term care insurance. There always seems to be a good reason for putting off such decisions. Taking out private loans for the full cost of higher education is a non-starter for those from poor backgrounds and many more. The state needs to be involved in all these markets. But it need not simply take on the whole cash burden. Individuals can decide to share the burden with some help.

Nudging forward?

Encouragingly, behind all the political sound and fury, steps have begun to be taken to put the funding of the welfare state on a sounder footing. The work of the Turner Commission (2005), looked squarely at the failure of past pension policy and the consequences of rising life expectancy, suggested that the age at which full state pensions could be drawn should rise in line with life expectancy, effectively ending the steady growth of life in retirement. State pension ages send important signals to individuals and private pension schemes too. The commission further recommended the creation of a national scheme that would take minimum contributions from employees and employers unless employees actively contracted out – a “nudge”, or better, a big shove, towards greater saving. It also said basic state pensions should be made more generous over time to give individuals greater incentives to build their own pensions.

It is remarkable, though relatively unremarked upon, that in the midst of all the cuts this cross-party strategy has survived with a clear and speeded up timetable.

Some of us, and notably the LSE’s Professor Nicholas Barr, have been urging a major reform of higher education funding for many years. This is now happening in a way that will require beneficiaries to pay a lot more towards the cost. This is not so much a nudge as a hefty kick up the backside. You do not have to agree with all the detail – such as no funding at all for teaching the humanities and social sciences! – to conclude that this is absolutely the right direction in which to go. With all the other fiscal pressures I have discussed, there will be less and less for universities from the ordinary taxpayer.

Similar tough options will face the government later this year when the Dilnot Commission on long-term care reports. Once again, I suspect, people will be called upon to share more of the cost of their care with the state.

All these are examples of what I have called “quasi taxes”. Bit by bit we may be nudging the electorate and users to pay for the extended life and longer education they are enjoying. But even if all these proposals are implemented, it will take higher taxes or more new ideas to balance the books in the long term.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2011 issue of LSE Research Magazine.

1 Comments