Paul Whiteley discusses his research into the relationship between enrolments in higher education and economic growth. He finds a significant positive correlation, meaning that the cuts in higher education funding could have negative implications for future economic growth.

Paul Whiteley discusses his research into the relationship between enrolments in higher education and economic growth. He finds a significant positive correlation, meaning that the cuts in higher education funding could have negative implications for future economic growth.

After the 2010 general election the newly elected coalition government in Britain introduced a radical new policy for the funding of higher education. The policy was to transfer eighty per cent of the costs of teaching in universities to the students, and so to effectively privatise this aspect of university funding for all but the STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). This is a remarkably radical policy with no precedent in Britain or in any other advanced industrial countries. It has already had the effect of reducing applications to universities in England by 8.7 per cent in 2012-2013. Moreover this has happened in a year when one would expect university applications to increase because there are more than 1 million young people currently unemployed in Britain. In a recession it makes sense for young people to invest in their future education in order to improve their chances in the labour market. Instead we have seen a hefty decline in enrolments.

In my paper ‘Economic Performance and Higher Education – the Lessons for Britain’ published online by the British Journal of Politics and International Relations in May 2012, I look at the relationship between enrolments in higher education and economic growth in the advanced industrial countries. The basic idea is to see what the economic consequences of this policy are likely to be in the long run if it deters significant numbers of young people from going to university. A second objective is to see if student enrolment in the STEM subjects does actually have a direct effect on stimulating economic growth, something which is frequently asserted by the science lobby and largely accepted by politicians.

Economic Growth has been a topic for research ever since Adam Smith wrote: “The annual produce of the land and labour of any nation can be increased in its value by no other means, but by increasing either the number of its productive labourers, or the productive powers of those labourers” (p 343, The Wealth of Nations, 1776). As this quote makes clear, Smith thought that education and training were key factors in stimulating growth. More recent research by economists like Robert Barro, Daron Acemoglu and Elhanan Helpman support Smith’s assertion that investment in education or ‘human capital’ as it is called, plays an important role in creating prosperity in a modern economy.

Researchers make a distinction between the role of education in economic development in third world countries and in the advanced industrial world. In a paper published in the Journal of Economic Growth in 2006 Jerome Vandenbussche and his colleagues argued that unlike developing countries, advanced industrial countries should invest in tertiary education in order to improve their human capital. By stimulating research and development, tertiary education can push back the frontiers of technological knowledge and boost growth. In contrast, developing countries are more advised to invest in basic forms of education, which will move them closer to the frontiers of technological knowledge.

With this in mind my paper looks at the relationship between enrolments in higher education in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or the advanced industrial countries, and economic growth over the period 1999 to 2008. With 29 countries and ten years of data for each country, it is possible to model the links between growth and higher education while at the same time taking into account other important variables which influence growth such as capital investment, trade openness and ‘catch-up’. The latter refers to the tendency of countries with relatively low standards of living to catch up on their richer competitors by copying their innovations. This is what China, Brazil and India are currently doing.

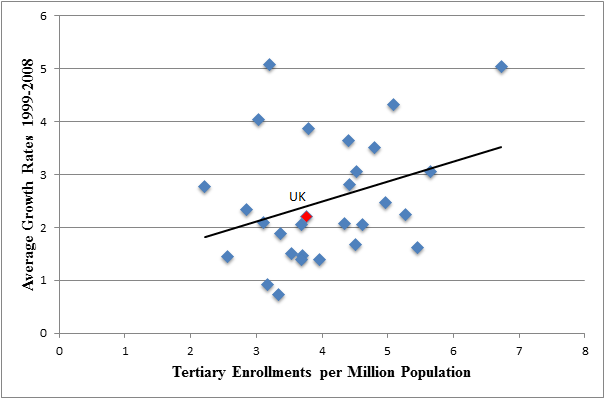

The modelling shows that enrolments in higher education play a very important role in stimulating growth in these countries. This can be seen in the following figure which compares economic growth and participation rates in higher education averaged across the OECD countries over the ten year period. The line summarizes the relationship and it indicates that greater numbers of students in higher education is associated with faster growth. The UK is the red diamond in the figure and it is below average for the OECD countries both in terms of student enrolments and in terms of economic growth. It is interesting that the country in the top right hand corner of the figure is South Korea which has the highest enrolments in the OECD and the second fastest growth rate.

Correlation = +0.33

One important question is whether or not enrolments in the STEM subjects stimulate growth. The analysis shows that once enrolments in general are taken into account, additional students in the STEM subjects have no impact on growth. It is higher education in general which matters not specific subjects. The science lobby has been pretty effective in convincing decision-makers that subjects like maths, physics and engineering boost growth and this explains why these subjects have been protected in the new funding regime. But there is no evidence to support this claim.

Once the model of economic growth is estimated it can be used to ‘re-run’ history. In other words, we can simulate the effects of different enrolments on economic growth in the past, and in this way see what the likely impact is of a drop in student numbers. Suppose the new policy had been introduced in 1999 and it had permanently reduced higher education enrolments by say 10 per cent over the period up to 2008. If this had happened it would have reduced economic growth in Britain by about 14 per cent each year.

This doesn’t sound much but a relatively small reduction in growth cumulates over time and turns into a large amount over the period of a decade. To put this in perspective, Gross Domestic Product increased in Britain by about £530 billion in current prices from 1999 to 2008. So a cumulative loss of national income of 14 per cent over this period represents a sum of about £74 billion. In contrast, according to the Office of National Statistics, total spending on Higher, Further, Continuing and Adult education in Britain from 1999 to 2008 was about £27 billion. There are no conceivable savings from the new regime which can offset the loss of revenue from slower growth. To be fair, enrolments may not fall by ten per cent in the long run, but it would be very surprising if the new policy stimulated the expansion of Higher education to the point that we rose above the OECD average. So it is very likely to have serious long term consequences.

The puzzle is that such a counter-productive policy could be implemented in such a short time without thinking through the unintended consequences. My own view is that this is because debates about economic growth in Britain have been captured by a financial and business elite discourse which argues that employment rights, the minimum wage and corporate taxation are the real obstacles to growth. Investment in education has little impact on this discourse, and therefore little influence on current government policy. In fact, as Adam Smith argued nearly two and a half centuries ago, the best way to stimulate growth is to educate the workforce, and in advanced industrial countries like Britain this means investing in higher education.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Paul Whiteley is Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

There is no doubt that Historically and Technically that the United Kingdom is a haven for foreign and Local students.

However as the article has rightly stated the UK has underinvested in Higher Education Since the Mid 1970s especially in fields of the future like the Sciences and Technology.

Siince the Mid 1960s the UK has produced far too many Arts Graduates in Law Journlaism and Finance to the detriment of even Medecine.

In the 1970s Britain Produced Cars and Machinery but today all are outsourced in Asias in places lile Hong Kong and Singapore a great slide for the Pioneers of the Industrial Revolution.

Meanwhile the greatest tragedy is that Fewer Native White Male Britons are studying and earnig Degrees and HNDS Compared with Indian Arab African and Asian Students with the Chinese in Particular.

Overall even at Key Facilities You see Asians like Indians and Chinese Persons managing UK nuclear Utilities and Factories something unthikable in a racist situation that they incurred upon arrival in the 1960s from Overseas.

Britain still has great talent in every field of endeavou.Her great past still affects the world today but she must catch up in Industry Once again like in the 1750s and one more thing English People Ought to learn other languages serioulsy like German Japanes and Chinese and forget about the Anglo Saxon Arrogance taken up by the Americans and the Canadians.

A word to the Wise in Britain is in the North of Scotland and England.