What are the lessons of history for the Treasury’s proposals to change the basis of UK pension taxation? The experience of the 1980s signals trouble ahead for both consumers and the state if the changes are implemented, argues Hugh Pemberton.

What are the lessons of history for the Treasury’s proposals to change the basis of UK pension taxation? The experience of the 1980s signals trouble ahead for both consumers and the state if the changes are implemented, argues Hugh Pemberton.

In its July consultation paper (Strengthening the incentive to save) HM Treasury outlined its plans to change the basis of UK pension taxation. It proposes to abolish the present system in which people saving for a pension are given tax relief on their contributions but the pension, when it is eventually taken, is taxable. Instead the Treasury proposes to tax contributions but for the pension in payment to be tax free. (Thus moving to a so-called Exempt-Exempt-Taxed or EET system to a Taxed-Exempt-Exempt, or TEE, system). In the Treasury’s view this will simplify the system, increase incentives to save and boost tax revenues.

But history suggest the proposed change is unlikely to achieve its professed long-term aims. Instead it is likely to reduce tax receipts, result in lower pensions for consumers, complicate the system, and decrease saving (in turn producing pressure for higher state spending). In other words it will fail comprehensively to achieve much that is positive apart from increased short- to medium-term tax revenues – which will be vastly outweighed by the long-term costs to the state and to individuals.

Anybody familiar modern British political history will know there is a consistent pattern of short-termist political decision-making that turns out to have unwelcome long-term consequences. Of all areas of policy, pensions are the most long-term and the proposals set out by the Treasury risk repeating such mistakes.

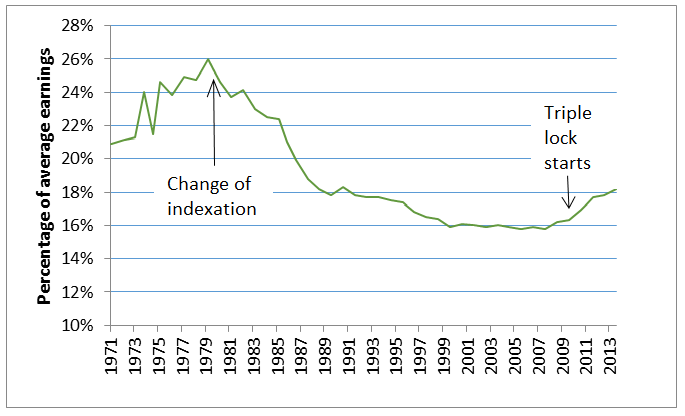

For an example from history, take one of the changes being examined by the AHRC’s Thatcher’s Pension Reforms project at the University of Bristol: the then Conservative government’s decision in 1980 to link increases in state pensions to the rise in retail prices instead of the rise in average earnings. This alteration, made entirely for reasons of short-term economy, looked small at the time but over the long-term the change, compounded annually, served to slash the value of the state pension from an already meagre 26 per cent of average earnings in 1979 to just 16 per cent within 20 years.

Figure 1: Erosion of BSP as a percentage of average earnings, 1980-2010

Source: DWP Abstract of Statistics, 2014.

The present proposals will have similar long-term consequences:

First, the loss of tax relief will remove an important incentive for people to save into their pension and so we can expect levels of pension saving to fall.

Second, because contributors will lose the capital growth on the value by which the tax relief raises their contributions their final pension pot will be smaller.

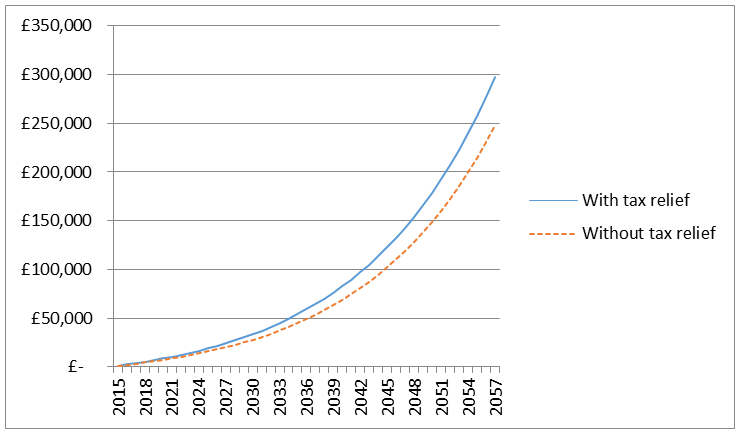

Figure 2: An illustration of fund growth with and without tax relief on contributions

Assumptions: 25 year-old makes contributions of £1000 p.a. to retirement on 68th birthday (c.4 per cent of current average earnings); income tax rate 20 per cent; annual rate of return on investment 7 per cent.

Third, receiving the pension tax free will probably not make up for this shortfall. On reasonable assumptions, a 25-year old today will find their pension will be 7 per cent lower in retirement under the proposed regime.

Fourth, over the long-term the initial revenue gained by initial tax relief on contributions will be significantly less than the tax revenue lost by paying the pension tax free (in our modelled example the total tax taken from this individual drops from nearly £40,000 to just £8,600).

Finally, the promise of simplification held out by the Treasury consultation document is an illusion. Like virtually every change to the UK system since 1945 implementation of this proposal would complicate not simplify the system – because pension contributions pre-dating the proposed tax reform will continue to yield a taxable pension and so there will actually be two parallel tax regimes.

We conclude that the Treasury’s consultation documents is an attempt to dress up a policy aimed at bolstering tax revenues over the short- to medium-term as a long-term reform to incentivise pension saving and improve the level of income replacement in old age. It is inconceivable that it will achieve either long-term aim.

We recommend that government should look to the long-term security of British pensioners and resist the temptations of a short-term boost to public finances from abolishing tax relief on pensions. If the Treasury is determined to reduce the cost of tax relief on pension contributions it should instead consider removing higher-rate relief, a costly subsidy to those least in need of an incentive to save into a pension.

Read the full version of the ARHC Thatcher’s Pension Reforms project’s response to the Treasury consultation.

Note: This post originally appeared in a shorter form on the Hugh Pemberton’s blog, Pensions History.

Hugh Pemberton is Reader in Contemporary British History University of Bristol, School of Humanities, Department of Historical Studies and Principal Investigator for the AHRC Thatcher’s Pension Reforms and their Consequences project. He tweets from @hugh_pemberton

Hugh Pemberton is Reader in Contemporary British History University of Bristol, School of Humanities, Department of Historical Studies and Principal Investigator for the AHRC Thatcher’s Pension Reforms and their Consequences project. He tweets from @hugh_pemberton