Kate Webb analyses the impact of the benefit cap which recently came into force. She observes that its failure to take regional variation into account means that unintended consequences at a regional level are inevitable, with the most likely instance of this being the effect on families in the south east who are paying high private rents.

Kate Webb analyses the impact of the benefit cap which recently came into force. She observes that its failure to take regional variation into account means that unintended consequences at a regional level are inevitable, with the most likely instance of this being the effect on families in the south east who are paying high private rents.

The overall benefit cap recently came into force, imposing a maximum ceiling on the amount of support a household can claim, regardless of need. It’s popular but controversial, both sentiments stemming in large part from its simplicity: by adopting a single, national maximum, the policy ignores the wide variations in rent that exist across the country.

Ministers have already been quick to hail it a success, although their claim that it has directly encouraged families into work was equally quickly refuted. It’s not sensible to pre-emptively judge the effectiveness of a policy: maybe the cap will boost work incentives; maybe concerns that the cap will increase homelessness will be unfounded. But it is surely reasonable to expect contingency plans to be in place in case the cap does create unintended consequences.

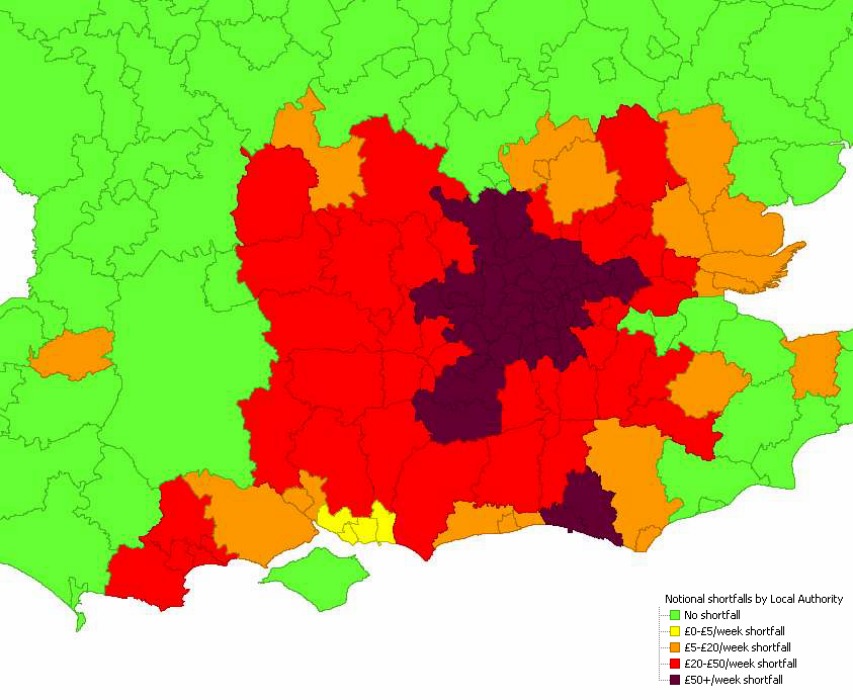

Impact of the overall benefit cap on 3-child families renting privately in the south-east

Capped households will lose an average of £93 per week. This will come entirely out of their housing benefit – money that families on low incomes have been allocated to meet housing costs. The map below demonstrates what this means for a family with three children renting privately. Due to high private rents, the cap will bite in the majority of London and the South East.

Faced with such losses, it’s not unrealistic that a significant proportion of those hit by the cap will be unable to pay their rent, and will therefore be evicted and be forced to turn to their local council to re-house them. This is a traumatic scenario for any affected family. But it’s at this point that the crudeness of the cap really bites. The Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) has insisted that the cap should remain in force even if a family is made homeless and put up in temporary accommodation by their local council.

It is estimated that 5,500 such families will be subject to the cap this year. This will severely restrict the ability of local authorities to meet their legal requirement to re-house homeless families. Even when a homeless family is placed in temporary accommodation by a local authority, they are expected to pay towards their housing costs. Sensibly, regulations therefore require that any housing offered to homeless families must be affordable.

This broadly means that families ‘can afford the housing costs without being deprived of basic essentials such as food, clothing, heating, transport and other essentials’. Non-housing benefit income (for example from income support or child tax credits) is set at a level designed to just about cover these costs. Local authorities cannot therefore expect families to subsidise the type of shortfalls the cap will create using non housing benefit income.

In order to find ‘affordable’ temporary accommodation, local authorities will have to place homeless families in the very cheapest areas. No accommodation will be affordable for larger families who stand to lose nearly all or all of their housing benefit, putting local authorities under financial strain as they struggle to meet the gap. Ministers have said that the overstretched and oft-cited Discretionary Housing Payments budget should come into play at this point.

The risk that the overall benefit cap will increase homelessness is a calculated one that Ministers have decided they are comfortable taking. But insisting that the cap continues to hit families made homeless because of the cap will trap homeless families and local authorities in a ‘ludicrous go around’ (to quote the words of one welfare minister). DWP could and should avoid this nonsensical scenario by exempting homeless families from the overall benefit cap before it rolls out nationally this summer.

This article was originally published on the Shelter policy blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Kate Webb is a policy officer at Shelter. To find out more about Shelter see their website and Twitter feed.