Ben Worthy writes that the unprecedented availability of public opinion and similar data means the fate of prime ministers is more tied to numbers than to rumour. At the same time, data itself can start to weave a narrative, and by doing so push events in a certain direction.

Ben Worthy writes that the unprecedented availability of public opinion and similar data means the fate of prime ministers is more tied to numbers than to rumour. At the same time, data itself can start to weave a narrative, and by doing so push events in a certain direction.

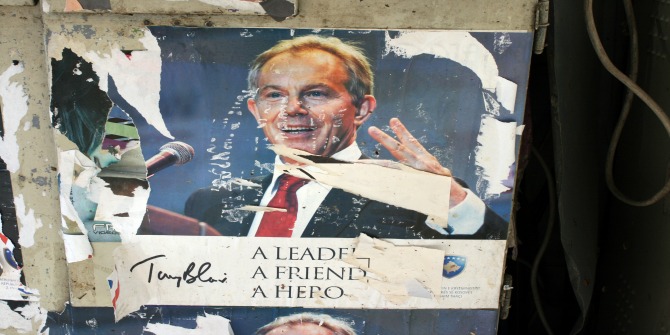

When do we really know if a Prime Minister is in trouble? Short of the obvious or the truly catastrophic, prime ministerial decline is an inexact science. Trouble in Turkey and in a Conservative dining club did for Lloyd George in 1922; an ill-advised tax and ill-advised attitude to Europe did for Thatcher, accelerated by a stalking horse no one had heard of. In September 2021, Johnson was said to be considering another ten years in office. Now it’s unclear if he’ll survive ten days or ten months. If he is removed or steps down, he’ll be the third Conservative leader who was removed or resigned in less than six years.

For much of history, ‘trouble’ for prime ministers happened backstage and behind closed doors. It was driven by a combination of events turning bad and the devil’s radio of backstage whispers, gossip, and speculation. It was what Harold MacMillan called ‘a process of mysterious osmosis’ refracted through MPs, party groups, and the media. Warning signs were often moans that a leader had ‘lost the back backbenchers’ or ‘failed to visit the tearoom’.

But in an age of data and datafication, can we see danger more clearly? Big data, social media, and instant polls mean we can more rapidly gauge the views of the public, party, and Parliament. Theresa May and Boris Johnson are perhaps the first two prime ministers whose decline can be ‘measured’ rather than guessed. A whole range of data and measures could help to tell us what and how much trouble and leader is in, and whether they’ll survive (take a look at May’s decline in six charts). Together, these data can craft a narrative than can be illuminating, while also becoming self-generating and self-fulfilling.

The public and what they think is one area now swimming with data. Of course, polls have always been important, and played a serious role in Thatcher’s decline. But they now arrive far more quickly with proliferating headlines. Polling can also tell us about what it is that’s driving the trouble and what ‘the people’ think should happen. In Johnson’s case, a substantial part of the population believe the ‘partygate’ revelations matter and two thirds think Johnson should stand down. Interestingly, the polls also tell us that, for all the claims of his Heineken like cut through, ‘Boris Johnson never was a popular Prime Minister’. His decline has actually been slow-moving over months rather than a cliff edge. Most importantly, the data becomes a political actor and provokes a response. Many Conservative MPs may well pause to think when polls tell them Labour are ahead and ‘the situation for the Tories is worse than you think’ because they are even farther behind in ‘marginals that matter’.

Another key group who are now endlessly polled and datafied are political parties themselves. Party members had seemed broadly supportive of Johnson but Conservative Home’s panel paints a bleaker picture, with 53% thinking he should resign now (though not quite Theresa May bleak, which was 73%). The data keeps flowing, with some Associations going public and others being polled anonymously by their MPs on Facebook. This data adds to the narrative and contributes or (even constructs) the all-important ‘voice’ or the view of the grassroots.

The view of the public and party then flow into Parliament itself. For prime ministers, the UK is, above all, an ‘over the shoulder’ democracy, as Anthony King put it. It is there that prime ministerial fates can be decided, and the ‘backstage’ and ‘frontstage’ of what leaders do become a source for more data. Backbench rebellions has always been a solid-ish marker of unhappiness and crisis. May’s fate seemed firmly mapped out when she suffered two defeats that made it first and fourth place in the top five defeats in modern political history. After that, it became a matter of ‘when’ and not ‘if’ she ended her premiership.

Johnson’s defeats, too, help us trace his decline. Could it be that the rebellion of late December sealed his fate? The Omicron-related rebellion was huge, and involved MPs from across his party, including the newest MP. The rebellion was also helpfully analysed by Johnson (and May’s) very own Former Director of Legislative Affairs on Twitter. Rebellions are not always about size, as Phil Cowley points out here, but also about what they reveal about unhappy parties, and what they symbolise and mean about prime ministerial authority.

Beyond structured events, prime ministerial problems also generate all sorts of other ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ data from Parliament. At one end are the obvious lists of MPs calling Johnson to resign. Mutterings in the tearoom can also take more solid form with WhatsApp messages (leaked or written to be leaked). There was this fascinating measure of Cabinet support by Sam Coates who ‘ranked in order of time the tweet, WhatsApp or interview was given’.

For a Conservative leader, though, perhaps the most vital data is missing: the tally of famous ‘letters’ to the 1922 committee. Only one person knows this number for sure, and he was accused of ‘sitting on them’ back under May (some MPs were helpful enough to publish their letters then). We know when the first one went in and there seems to be 35, but now that they can be emailed too, the picture is much less clear.

Unlike their predecessors, May and Johnson’s fate seemed tied to numbers and data rather than rumour. The danger is that data and numbers start to weave a narrative, and push events in a certain direction. Phrases like ‘all-time low’, ‘grassroots pressure’ and ‘worse in the marginals’ give a sense of inevitability and momentum, and no one is saying that there are ‘only’ 35 letters. A Prime Minister who was always flexible with numbers may find his end sealed by hard data.

____________________

Ben Worthy is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck, University of London. Ben’s paper on Prime Minister’s “Ending in Failure? The Performance of ‘Takeover’ Prime Ministers 1916-2016” (November 17, 2016) is available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2904948

Ben Worthy is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck, University of London. Ben’s paper on Prime Minister’s “Ending in Failure? The Performance of ‘Takeover’ Prime Ministers 1916-2016” (November 17, 2016) is available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2904948

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash.