Based on research conducted by the IFS, David Phillips examines the kinds of tax and spending decisions that may face a newly independent Scotland in its first few years. What is clear is that in or out of the UK, hard fiscal choices are going to have to be made.

Based on research conducted by the IFS, David Phillips examines the kinds of tax and spending decisions that may face a newly independent Scotland in its first few years. What is clear is that in or out of the UK, hard fiscal choices are going to have to be made.

In the run up to elections politicians are often less than fully open about their plans for taxes and spending. They often claim that they will only know what is necessary when they attain office and “open the books”. But while the UK government may not be a paragon of openness, there is usually ample information available to know broadly what fiscal decisions are likely to be necessary after an election.

The referendum on Scottish independence is of course rather different to a general election. And the uncertainties regarding the medium term economic position of an independent Scotland are significant. But we can already say quite a lot about the kinds of tax and spending decisions that may face a newly independent Scottish nation in its first few years.

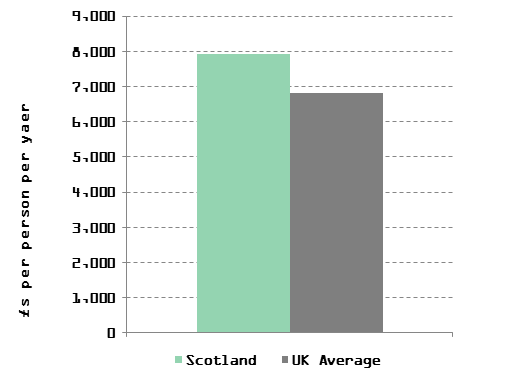

The basic facts are straightforward and, broadly, uncontested. Ignoring North Sea Oil, taxes raised per head in Scotland are similar to those raised in the rest of the UK: a little more is raised from VAT and duties, and a little less from income tax. Given that incomes (again ignoring North Sea Oil) per head are also similar this is not surprising. Public spending per head on the other hand is 11% higher (see figure 1 below. That greater level of spending is driven almost entirely by spending devolved to the Scottish government. Indeed public service spending in Scotland – that is broadly spending other than on social security and debt interest – is nearly 17% higher per person.

Figure 1: Public service spending per person is higher in Scotland than in the UK as a whole

Source: Scottish and other government statistics and IFS calculations

The Scottish Government’s ‘Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland’ statistics show that in recent years, that gap – similar taxes and higher spending – would have been just more than “paid for” if North Sea Oil and gas revenues were allocated to Scotland on a geographic basis. But that does not mean that an independent Scotland could avoid some sharp fiscal decisions.

First, the fiscal situation for the UK as a whole remains difficult. The UK is expecting to borrow about £120 billion this year with national debt forecast soon to reach 85% of national income. The Treasury is expecting to reach “structural balance” on day-to-day spending by 2017-18 only through the imposition of further significant spending cuts already announced for between now and 2015-16, and even bigger ones, the details of which have not been set out, in the subsequent two years. These cuts would hit Scotland just like the rest of the UK.

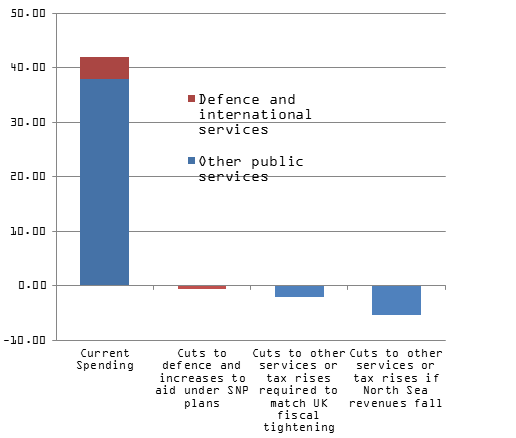

It is unlikely that an independent Scotland could run a looser fiscal policy than the UK as a whole. So even starting from a position of parity with the rest of the UK, big fiscal choices would already be necessary for a Scotland independent from 2016. Matching the fiscal tightening being planned by the UK would mean the government of an independent Scotland having to make cuts of about £2.5 billion in its first two years (to get a sense of scale, spending on public services for Scotland was £42 billion in today’s prices in 2011–12, the latest year for which data are available).

Second, estimates by the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) suggest that oil revenues will decline over the next few years. In research published last month, we showed that on the central OBR estimates, this could increase the Scottish budget deficit by a further £3.4 billion in today’s terms. Dealing with this would require spending cuts or tax increases of a similar magnitude on top of the £2.5 billion implied by the UK government’s plans.

Of course, estimates of future oil revenues are highly uncertain. The Scottish Government’s estimates, based on alternative oil price and production forecasts, are more optimistic, with higher revenues over the next 4 years than suggested by the OBR. Indeed, in some of their scenarios, an independent Scotland would, in principle, be able to cut spending or raise taxes by less than if it remained part of the UK, at least during the first few years of independence.

The temptation in these circumstances may be to tax less or to spend more. But this might be ill-advised. An independent Scotland might want – or indeed need – to maintain a stronger fiscal position than the UK, both in order to gain credibility in the financial markets and as preparation for the longer-term fiscal challenges of an ageing population and the eventual inevitable decline of North Sea revenues. Indeed, over the medium term, a Scottish government should target a measure of borrowing which excluded all, or most, of North Sea revenues, as recognised by the second report of its independent Fiscal Commission.

Thus, the first few years of independence would see a government of Scotland needing to raise taxes or cut spending –and unless North Sea revenues rebound sharply, the cuts or tax rises look likely to be greater than those required in the UK.

The good news is that there is scope for change, and indeed some plans. On the spending side the SNP have already said that they will look to spend less on defence than the UK currently does “on behalf of” Scotland. On their current plans that would save around £900 million annually. In fact even that would leave Scottish defence spending rather higher than that of most small, rich nations. On the other hand they have indicated an aim to increase overseas development spending to a level which would make Scotland one of the most generous aid donors in the world relative to its size. That would be a big call for a newly independent Scotland facing significant fiscal pressures.

Figure 2: Substantial cuts to public service spending may be required in the first few years of independence if North Sea revenues decline as expected

Source: Scottish and other government statistics, OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Centre for Public Policy in Regions analysis, SNP policy statements, and IFS calculations

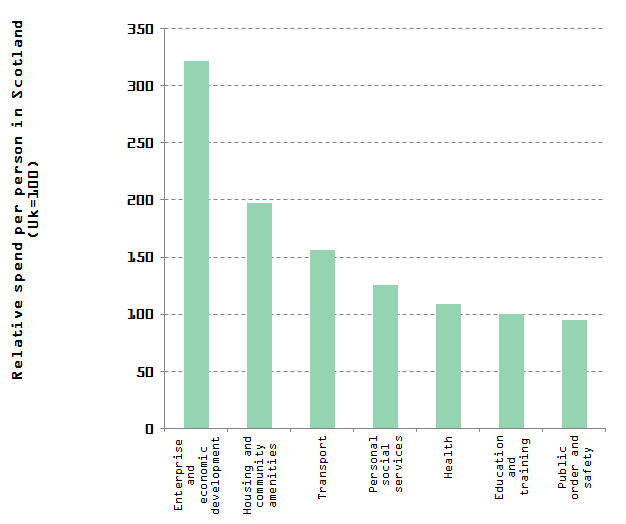

Beyond that, on the spending side, the obvious place to look for savings might be where Scotland currently spends more per head than the rest of the UK. Here the picture is rather interesting. The devolved Scottish government has not chosen to focus its additional resources on the two biggest public services – health and education. Indeed, despite additional support for the HE sector following the decision not to introduce top up fees, spending on these two big services is now at a level not much higher than in the rest of the UK. Spending per person on law and order is slightly lower than the UK average.

Rather it is spending on a whole host of other services – transport, agriculture, social services, housing, economic development – which is proportionately very much greater than spending in other parts of the UK (see figure 3 below). Indeed spending on these services is on average 50% per person greater and the gap with the rest of the UK has been increasing over time.

Figure 3: Spending per person in Scotland relative to UK

Source: Scottish and other government statistics and IFS calculations

Of course there is no need to make any fiscal adjustment on the spending side alone. There is a good chance that taxes will go up across the UK after the next general election (as it did after 1992, 1997, 2001, 2005 and 2010). Like the UK as a whole, an independent Scotland would get most of its revenue from income tax, VAT and National Insurance Contributions and would find it hard to raise significant sums without raising more from at least one of these sources.

On the tax side though an independent Scotland would have exciting opportunities to reform, simplify and make a more efficient tax system: the UK’s system has become too complex and distorting and imposes unnecessary economic burden. How brave the government of a newly independent Scotland would be in taking on really radical tax reform though we cannot yet know.

What is clear though is that in or out of the UK, hard fiscal choices are going to have to be made. Careful analysis of “the books” already available means we know the potential scale of these choices. But there remains much to debate about quite what choices will be made on taxes and spending both in an independent Scotland, and in a Scotland that remains part of the UK.

This blog post is based on an article by Paul Johnson and David Phillips published in the Scotsman on the 19th of September 2013 and draws largely from the most recent IFS report on public services in Scotland.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

David Phillips is a Senior Research Economist, currently working in the Direct Tax and Welfare sector and the Centre for the Evaluation of Development Policy (EDePo@IFS). Most of David’s work is arranged around the broad themes of poverty, inequality and the tax and benefit system and includes projects both in the UK and in middle income countries.

The author gratefully acknowledges funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS (grant reference ES/H021221/1). The ESRC is supporting a programme of work addressing issues around the future of Scotland. One of the strands focuses on supporting new work at current major ESRC investments before and potentially after the referendum. The IFS has published three reports as part of this research programme so far:

“Scottish independence: the fiscal context”

“Government spending on benefits and state pensions in Scotland: current patterns and future issues”

“Government spending on public services in Scotland: current patterns and future issues”