The UK electorate will vote on whether to exit the EU in a referendum before the end of 2017. Costas Milas writes that it is important that for David Cameron and the government to monitor closely whether ‘Brexit’ talk continues to receive, in coming months, the attention of the EU public. This will help form a set of realistic demands while also ensuring that expectations at home remain well-anchored.

The UK electorate will vote on whether to exit the EU in a referendum before the end of 2017. Costas Milas writes that it is important that for David Cameron and the government to monitor closely whether ‘Brexit’ talk continues to receive, in coming months, the attention of the EU public. This will help form a set of realistic demands while also ensuring that expectations at home remain well-anchored.

David Cameron’s in/out EU referendum is planned to take place before the end of 2017. As things stand, an arguably slim majority of British voters appears to be rejecting Brexit. Yougov poll data suggests that around 44 per cent would vote to stay in, 36 per cent would vote to leave and 17 per cent don’t know (yet).

Part of the ‘in’ vote could be driven by expectations that David Cameron will be able to negotiate a new relationship between Britain and the EU that is ‘better’ for Britain. Indeed, what is the purpose of voting ‘in’, let alone the (already divided into the very issue) government motivate us to do so, if a ‘better deal’ with the rest of the EU is out of reach?

Nevertheless, expectations of how negotiations between David Cameron and his EU partners will evolve have to remain realistic (a point also flagged by Chris Giles at the Financial Times in a recent piece entitled “To avoid Syriza’s fate over the EU, Britain must embrace fudge“). Indeed, unreasonable expectations of how easily or swiftly EU can be ‘reformed’ are bound to be crashed in which case disappointed voters will move firmly into the ‘out’ camp. So, David Cameron faces a tricky task of keeping expectations at home in check. But how, can he do this?

To answer this question, one has to look at information contained in web search intensity. Indeed, recent academic research has shown that web search intensity can predict economic and financial events. For instance, Beracha and Wintoki find that online search activity predicts price movement of residential home sales and Joseph, Wintoki and Zhang find evidence that online search activity predicts stock price movements.

Extension of the above findings to political events is also worth paying attention to. In fact, a brand new academic study by myself and colleagues found that ‘Grexit’ talk has been able to predict, since 2010, the rising cost of long-term borrowing mainly in Greece, and to a much lesser extent in peripheral Eurozone countries (namely Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy).

If ‘Grexit’ talk has been found to hold some predictive power for Eurozone’s periphery can we make anything of ‘Brexit’ talk and its possible forecasting ability? Let us consider a simple online search of the keyword ‘Brexit’ and what it might mean for our relationship with the rest of the EU.

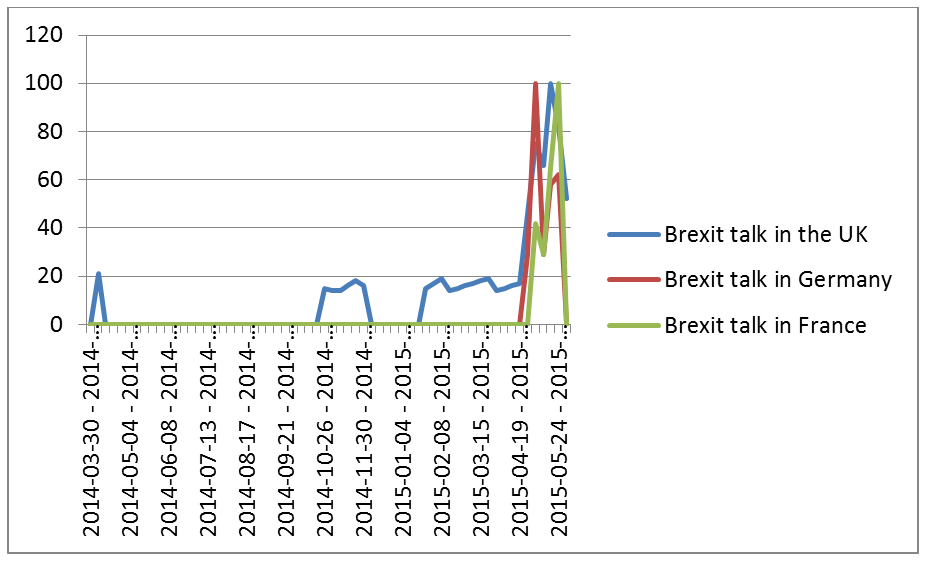

Google.com/trends boast that, in 2014, we searched trillions of times. This is indeed impressive but not very useful as it covers anything you can think of from say, holiday destinations to celebrities and their turbulent love affairs. Let us then narrow down the online search to ‘Brexit’ talk. Unsurprisingly, ‘Brexit’ talk reached a peak immediately after the May 2015 general elections when it became clear that, with Conservatives forming a robust government on their own, the EU referendum is firmly on. Clearly, ‘Brexit’ talk is heating up at home. This, we know. What is also useful to learn is whether ‘Brexit’ talk is of any interest to our EU partners and in particular Germany and France who arguably hold the key-power to make (if any) concessions to Britain. As it happens, Google Trends shows that Brexit talk in Germany and France has only just started to attract some attention (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Brexit talk in the UK, Germany and France (weekly data), March 2014-June 2015

Note: The Brexit talk index does not deliver the exact volume of queries but rather a normalized index of search intensity where a value of 100 corresponds to the peak search

Whether Brexit talk continues to attract the interest of our EU partners in the coming months remains to be seen. That said, this very interest can be monitored in real time.

If Brexit talk was to fade rapidly in Europe, EU politicians would become increasingly unwilling to make (significant) concessions. Indeed, why should EU politicians give in to Britain’s ‘demands’ if their electoral base finds ‘Brexit’ quite an uninteresting issue to worry about? On the other hand, a rapidly rising interest in ‘Brexit’ talk across Europe would arguably put pressure on EU politicians to pay closer attention and indeed deal with Britain’s demands in a more thoughtful manner.

Therefore, to manage home expectations regarding a successful renegotiation of our position in Europe, David Cameron and his government advisors would need to monitor closely whether Brexit talk continues to receive, in coming months, the attention of the EU public. Indeed, keeping an eye on real-time online ‘Brexit’ discussion across Europe will help us form and discuss with our partners a set of realistic demands while, at the same time, ensuring that expectations at home remain well-anchored. The less anchored expectations become, the less likely these expectations will match reality, in which case, voters will turn so much disillusioned that an ‘out’ vote will become almost unavoidable.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance at the Management School, University of Liverpool.

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance at the Management School, University of Liverpool.

Just read Mr Milas’s article in the Greek publication ekatimerini.com warning the British voters about the periled of Brexit. He describes a doomsday scenario centred around higher borrowing costs due to reduced credit ratings and the difficulty of negotiating individual trade agreements with EU countries to replace the blanket agreement that comes with EU membership. He completely ignores the fact that the UK will have unrestricted freedom to negotiate favourable trade deals with the major emerging markets outside the EU (Brazil, China and India for example;) and that there is no reason whatsoever why the UK cannot conclude equally favourable agreements with individual EU countries just as Switzerland has done. Such a portfolio of agreements may be higher maintenance than the simple EU umbrella but that is what capable energetic ministers are there for, and it’s a small inconvenience considering the £ 13 billion annual saving in contributions to the EU (also ignored in the article) and the benefits of new trade agreements beyond Europe. The article assumes that Britain will be disadvantaged and left behind outside Europe without entertaining the probability that the EU, with its ongoing immigration and economic crises, having to support its own dead wood with reduced funds after Brexit, having to finance the endless bailouts to Greece and whichever dysfunctional state follows next, and with brooding disillusionment growing among the populations of some members, and with the Schengen Agreement in tatters, may itself be the lame duck whilst the UK forges ahead. As such, the article is blatantly and absurdly biased, and is clearly designed to support the “in” campaign. One senses an anterior motive behind the whole piece.

“This will help form a set of realistic demands while also ensuring that expectations at home remain well-anchored.” – sounds ominous. We want out, EEA/EFTA will do for the time being, but we definitely want control of the country brought back into the hands of the people of Britain.