The Liberal Democrats’ policy priorities in government owed more to the preferences of elite decision-makers than to those of the party’s supporters, writes Christopher Butler, a fact that explains why the party broke their pledge to oppose increasing student tuition fees.

The Liberal Democrats’ policy priorities in government owed more to the preferences of elite decision-makers than to those of the party’s supporters, writes Christopher Butler, a fact that explains why the party broke their pledge to oppose increasing student tuition fees.

It is widely expected that parties will be broadly responsive to the preferences of their voters for their own electoral self-interest, yet it is not hard to think of examples of parties in power pursuing electorally costly decisions. In recently published research, I traced the decision-making process behind the Liberal Democrats’ notorious U-turn on tuition fees to better understand why parties sometimes fail to respond to their voters. Through interviews with over a dozen key figures involved in the decision-making process, I found that the party had little awareness of its supporters’ views and took decisions which were based more on the policy preferences of its senior MPs than of its supporters.

The Liberal Democrats entered government in 2010 as part of a coalition, after some 65 years out of the corridors of power in Westminster. Having finally got back into government, the party’s initial strategy was to focus on delivering the four policies which had featured on the front page of the manifesto (of which tuition fees deliberately was not one), on the assumption that these were the policies which had secured its support at the 2010 election.

Astonishingly, there was little attempt to understand who had voted for the party in 2010 and which policies or policy areas those voters might want to see the party focus on. The party did not start using public opinion research to understand its voters’ preferences until the arrival of Ryan Coetzee as Director of Strategy midway through the coalition. As one former adviser commented, it turned out that a lot of Liberal Democrat support came from

…broadly public sector workers who were being hit in numerous different ways with the policy choices we were making. Fees is probably a good example but certainly not alone; NHS reforms, pension caps, wage caps this kind of stuff; hugely problematic for them. (Interview, 2018)

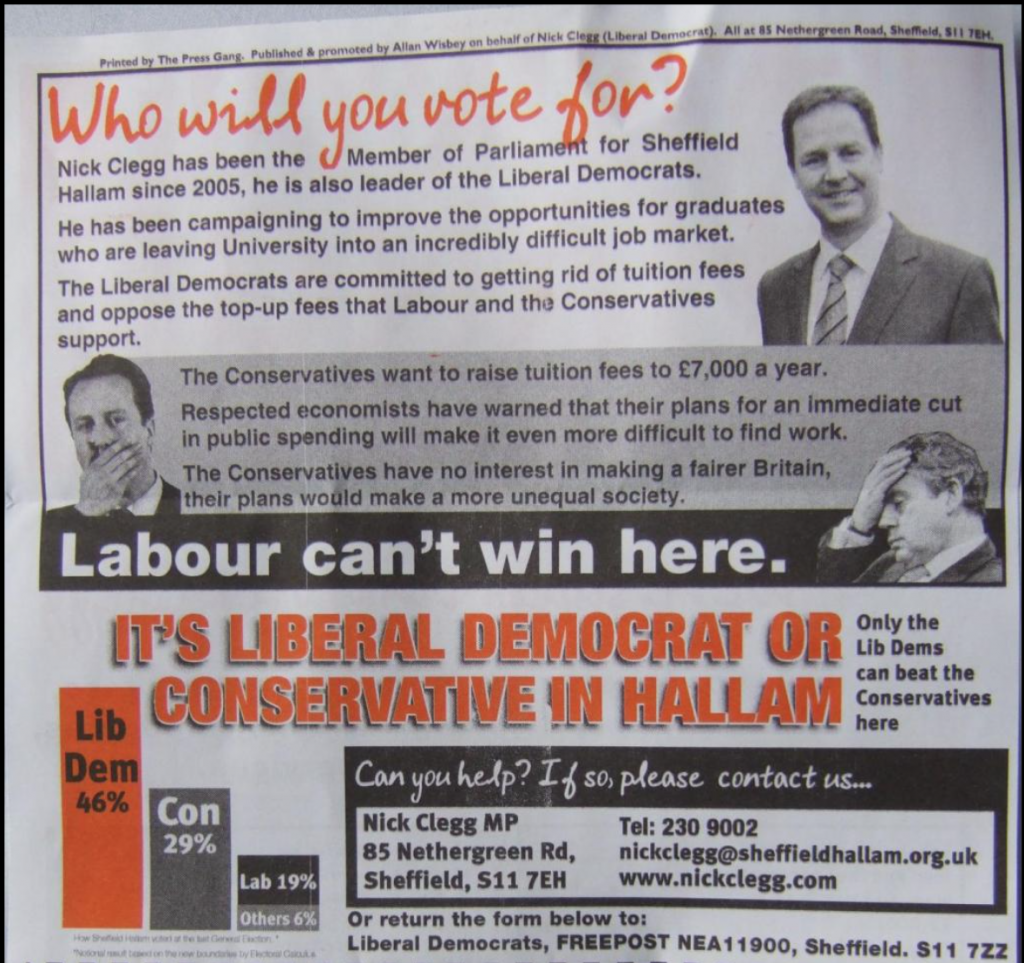

It was somewhat naïve to assume that Liberal Democrat support was predicated on the four policies which appeared on the manifesto front page: raising the income tax allowance, introducing the pupil premium, electoral reform, and the environment. The assumption that tuition fees was not integral to the party’s electoral support in 2010 ignored that successful constituency campaigns (including Nick Clegg’s) were campaigning on opposing tuition fees, ignored the party’s own polling that its position on fees was one of its most popular, and presumed that voters would not recall high-profile policy commitments from previous campaigns.

Sheffield Hallam Liberal Democrat leaflet, 2010 election

Available here.

Available here.

It is often forgotten that Nick Clegg and other senior MPs had tried to drop the party’s opposition to tuition fees before 2010, but had been forced by the party’s Federal Policy Committee to retain an aspiration to phasing out tuition fees in their 2010 manifesto. Clegg and other senior MPs, including the Cabinet Minister responsible for Higher Education Vince Cable, were resistant to abolishing tuition fees on the basis that such a policy would be regressive, whereas policies such as the pupil premium would do more to tackle educational inequality.

Quite a lot of us had taken the view for a long time that opposing tuition fees was ridiculous. It was the only fair and sensible way to fund universities and we should stop objecting and start arguing to make the system fairer, but not reject it in principle. (Interview with former MP, 2018)

This policy preference seems to have clouded Liberal Democrat decision-makers’ judgment. Since they had concluded that abolishing tuition fees would be a regressive move, they convinced themselves that voters would not support it when presented with the facts.

In theory, on paper it was a good scheme, it was better than the existing scheme in fact for anybody perceptive enough to work out the arithmetic. I was persuaded, I persuaded myself, that that would be good enough. (Interview with former MP, 2018)

Decision-makers also convinced themselves that since New Labour had also U-turned on increasing tuition fees in 2003 yet gone on to win a subsequent election, the Liberal Democrats could also survive any electoral storm arising from their own U-turn. This overlooked the considerable evidence that students were a more substantial part of the Liberal Democrats’ electoral coalition than they had been of New Labour’s, and the fact that abolishing tuition fees and opposing the Iraq war were the past most known policy positions.

The assumptions made by Liberal Democrat decision-makers about how voters would respond to the party’s U-turn on tuition fees appear to be driven by motivated reasoning. Since decision-makers had a clear preference not to abolish tuition fees, they did not seek or prioritise information which suggested that their strategy would be electorally damaging.

The very fact that the Liberal Democrats had been out of government for many decades may offer another reason as to why they prioritised policy goals over electoral self-preservation. Politicians who are more motivated by the rewards of office are unlikely to join the Liberal Democrats since they have been so far from power for most of the post-war period. Therefore the party may attract politicians who are more motivated by achieving policy than by achieving power.

Yet despite the failure of the party to understand and respond to its voters during the coalition years, discussion about the party’s electoral strategy has been notably absent from the three leadership contests that have taken place since. Even with evidence of a core Liberal Democrat vote emerging, largely in the South East and London, both current leadership candidates – Ed Davey and Layla Moran – are claiming that the party can win parliamentary seats across the country. Can the party yet learn the lessons from its past about the need to listen and respond to its voters?

___________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in British Politics.

Christopher Butler is a PhD candidate in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Manchester.

Christopher Butler is a PhD candidate in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Manchester.

Very interesting and it was indeed astonishing that the Lb Dems were not polling their own members before the Coalition. But there are plenty of other mechanisms by which members could signal their preferences and senior Lib-Dems must have been aware of member views. The move certainly saw LibDem support from students fall sharply, but I wonder if support for austerity was even more potent in collapsing the LIbDem vote given the findings that most LibDem members were either in or associated with the public sector.