The London mayoral campaign provides insight into what we can expect to hear from candidates for Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) that are to be introduced later this year. Tim Newburn sees this as a mixed bag. On one hand, the misuse of statistics will lead to confusion and mistrust of those standing for office, and, in reality, the ability of mayors and PCCs to drastically affect crime rates is profoundly limited. On the other hand, and more positively, it might stimulate vigorous debate on crime and justice issues and give an opportunity for the introduction of innovative ideas.

The Mayoral elections in London are the latest opportunity for us to see how politicians talk about crime, and how they use crime-related matters in their electoral campaigns. Since the 1970s crime has been a fairly significant issue in national politics. With the advent of elected mayors it has become a local electoral issue also, and indeed such concerns take on new resonance this year with the introduction of Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs). These individuals, established thanks to the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011, will have very substantial powers over local police services and more broadly over crime prevention budgets. Elections will be held in November 2012 for the 41 PCCs that will replace local police authorities across England and Wales (outside London).

This is a radical set of changes by any standards and, understandably, there has been much speculation about how they will work in practice. Who will stand? What types of promises will they make in relation to policing and crime? And will the reforms lead to greater public engagement in such issues? The London Mayoral contest offers one early indicator of possible answers to some of these questions, particularly how these elections might be fought, for the Mayor (or currently, and somewhat ironically given that one of the core aims in bringing in the new reforms was to increase democratic accountability, an unelected deputy-Mayor) is, in effect, the PCC for the capital.

There are six candidates for the Mayoralty. The incumbent, Boris Johnson, and his predecessor, Ken Livingstone, represent the two main political parties, and are clearly the two headline candidates. They are joined in the contest by ex-Metropolitan Police officer, and Lib Dem candidate, Brian Paddick, the Green Party’s Jenny Jones, an independent, Siobhan Benita, and the UKIP candidate, Lawrence Webb. The first five have issued full manifestos, and indeed both Johnson and Livingstone have specific crime and policing manifestos. They make for interesting reading.

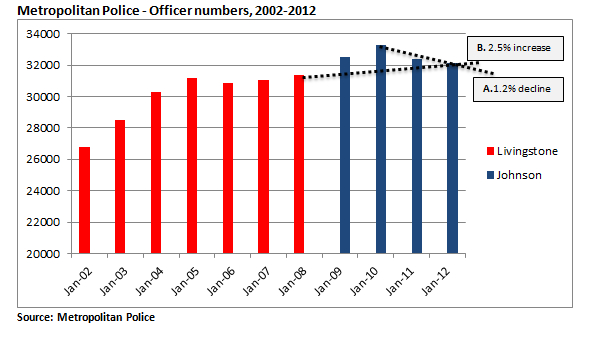

Predictably enough, the headline arguments concern crime levels and police numbers – and this may well give us some flavour of elements of the forthcoming PCC elections. All five mayoral candidates argue that police numbers are important and should, if possible, be increased. There has been something of a spat between the present Mayor (since 2008) and his predecessor, who was a two-term Mayor from 2000-2008, about their respective records in this regard. Each implies that the other cannot be trusted on police numbers. The opening of Livingstone’s manifesto promises to ‘reverse Johnson’s cuts’. Boris, he argues, has recently been forced to admit that numbers have dropped by 1,700 since 2010. Johnson, by contrast, argues that through his careful management of the Met’s budget during the financial crisis ‘there are now 1,000 extra officers on London’s streets’.

The question inevitably asked is ‘who is correct?’ The answer, roughly speaking, is that both are about right. It all depends what one measures, and what one’s time lines are. So, police officer numbers do appear to have dropped by a little over one per cent since the end of the last budget for which Livingstone can reasonably claim responsibility – 2008-09 (see line A above). However, it is also true to say that, at the time of writing, the overall number of officers is slightly under 2.5% higher than was the case when Livingstone left office (line B above). Where does this leave the electorate? Sadly, I suspect, confused and no less mistrustful of statistics – and politicians – than they were before. With the advent of elections for PCCs in November we can probably look forward to considerably more of this rather devious use of figures. I hold out little hope that the end result will be public enlightenment.

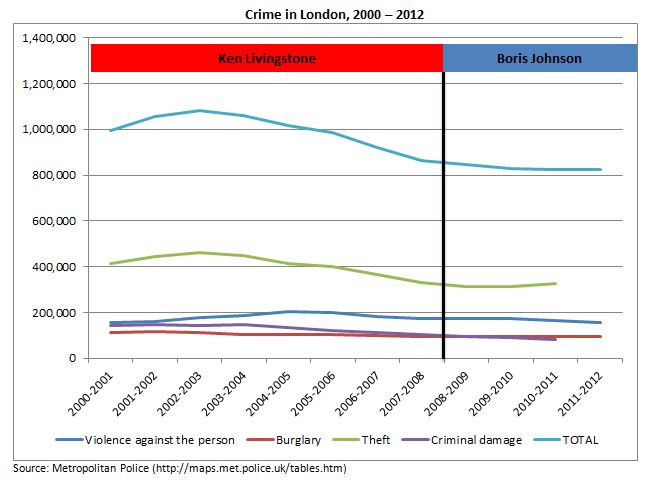

The second big dispute has been over crime figures. Once again, a quick look at the manifestos and you could be forgiven for getting rather confused. Boris Johnson begins by saying ‘I have put more police on the streets, brought crime down significantly’ and goes to on to say, ‘comparing my term with my predecessor total crime has been cut by 10.8 per cent’. Ken Livingstone takes a different view: ‘overall crime was cut significantly when I was Mayor and continues to fall. But the rate of decline has slowed to just one per cent, and Metropolitan Police statistics show that serious crimes such as robbery, residential burglary and rape are all rising’. Once again, whilst neither candidate can be accused of offering deliberate untruths, we are once again in the land of what at best can be described as selective interpretation and use of statistics. The graph below illustrates trends in overall crime, violence, burglary, theft and damage since 2000.

It does indeed show something of a flattening of the downward trend in recent years as Livingstone alleges but, equally, the claim carefully ignores the fact that crime increased during Livingstone’s first term (2000-04), before beginning its decline. On the other hand, Johnson’s claim that ‘total crime has been cut by 10.8 per cent’, whilst true, ignores the fact that in Livingstone’s second term crime dropped by 15 per cent. As to Ken’s suggestion that various serious forms of crime (burglary and rape for example) there are two responses. First, the rise in domestic burglary is relatively small and the overall total remains lower than in all but one of the years Livingstone was Mayor.

Second, the issue of recorded rape in the capital is likely to be a rather different matter. Whilst in most categories of crime a rise in the number of recorded offences might be considered a generally bad thing, this is not necessarily the case with rape. Historically, serious sexual offences against women suffer from very low reporting rates – for a variety of reasons but often because victims are doubtful that any serious action will be taken against the perpetrator. A rise in reported and recorded offences, therefore, rather than reflecting any underlying change in the number of sexual offences being committed, may be a product of a greater willingness to report. In this regard, the substantial funding provided to four Rape Crisis Centres in London over the past four years is likely to have been very significant. Quite possibly, therefore, the rise in this particular category of recorded crime may be to the credit of the current Mayor rather than a criticism of his tenure.

The long and the short of all this is that the political manifestos are hardly designed to elucidate, still less educate. Is this a problem? I think so for at least two reasons. First, not only is the electorate likely to be confused by what has been happening to crime, but their expectations about what it is possible for a Mayor to do about these things is being unrealistically heightened. The truth is that though the Mayor has fairly extensive powers over police budgets and increasingly over policing strategy, their ability drastically to affect crime rates is profoundly limited. Such matters are influenced much more significantly by broader socio-economic circumstances. Thus, for candidates of any hue to claim responsibility for crime trends is to stretch credibility more than somewhat.

The second danger is that the electorate becomes ever more disenchanted with politicians’ promises and claims, and that trust in statistics falls even lower than is already the case. Great efforts have been made in recent times (under both Labour and Coalition administrations) to organise national crime statistics in ways that reinforce their integrity and independence, and to produce local crime data that are accessible and informative. It would be a great pity – to put it mildly – if these efforts were undermined by ill thought-through local electoral campaigns.

All is not lost, however, for there are other aspects of the manifestos which provide a more positive illustration of the democratic potential bound up in the Mayoral campaign and future PCC elections. Again, I would draw attention to two matters. The first is the extent to which, in broad brush terms, there is agreement among the candidates. That is to say, there is territory which is largely shared by the candidates and which suggests elements of consensus in policing and crime matters. Indeed, these are actually quite numerous. All wish to see police numbers protected – though they have slightly different models for how this might be achieved. All highlight the importance of ‘Safer Neighbourhood Teams’ – local policing teams based in each of the 624 council wards in London – and offer different prescriptions for building on them. All candidates highlight the importance of tackling domestic violence and sexual violence against women. The four existing Rape Crisis Centres get the thumbs up, and promise of financial support, all round. Tackling hate crime appears in most manifestos. In short, beneath some of the potentially unhelpful headlines there are many matters which candidates see as a priority for support and action. Furthermore, and counteracting fears that electoral competition around crime matters inevitably leads to greater punitiveness, much of the shared territory is of a generally progressive character.

Secondly, the election has also provided an opportunity for candidates to introduce and highlight their own particular concerns and priorities. This offers the potential for a range of ideas to be put before the public to a degree, and in a way, that might otherwise be extraordinarily difficult to achieve. In the current manifestos, these include:

- Much greater resources for restorative justice initiatives (Jenny Jones)

- Investment in detached youth work in high crime areas (Brian Paddick)

- A victims commissioner for London (Ken Livingstone)

- Very significant reform of stop and search powers and procedures (Brian Paddick/Jenny Jones)

- Direct entry scheme to the Metropolitan Police (Boris Johnson)

- Resources and support for Citizen patrols – ‘Paddick Patrols’ (Brian Paddick)

- Campaigning for the decriminalisation of all drugs and the legalisation of cannabis (Jenny Jones)

- Trial schemes to allow night buses to stop on request (Brian Paddick)

- Compulsory sobriety schemes for alcohol abusing offenders (Boris Johnson)

Some of the most innovative and occasionally unusual ideas have come from the least favoured candidates. However, whilst they may not be elected Mayor, their participation in the process brings the benefit of raising ideas in the public domain that would otherwise remain unspoken or at least unheard. Moreover, it is just possible that some of these ideas, if they appear to gather some public approval, might be picked up by the eventually successful candidate. Siobhan Benita, the independent candidate, has a little box at the end of her manifesto entitled ‘policies from other candidates I support’, and this is something that others would do well do copy. As regards pinching particular ideas, two that I particularly liked were Brian Paddick’s suggestion of an Ombudsman for the Metropolitan Police and Siobhan Benita’s proposal for a full-scale independent review of the Met – to be established after the Olympics and to run for approximately a year.

If we take the London Mayoral election as a straw in the wind for the forthcoming PCC elections there are somewhat mixed messages. On the down side, I’m concerned about how crime statistics will be (mis)used and, consequently, would advocate the use of statistical monitors, possibly nominated by the Royal Statistical Society, to offer independent judgement on the various claims likely to be made. On the up side, we can potentially anticipate vigorous debate around crime and justice matters, including the airing of innovative and potentially progressive crime policies.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

About the author

Tim Newburn is Professor of Criminology and Social Policy and Head of the Social Policy Department, London School of Economics.

Thanks for pointing that out Ian (I had missed them altogether – it wasn’t deliberate). I’ve had a quick look at their ‘manifesto’ – which is no more than a couple of pages of A4. Little of substance, bar the frankly confused promise on the one hand to “adopt a hands-on approach to police operational matters in Greater London to deal with the current lack of coordination and training which became evident during the August 2011 riots”, whilst simultaneously promising to “end politically correct interference in police operations and restore colour-blind policing so that everyone is treated equally”. So, hands-on but not interfering! That should end the confusion around ‘operational independence’!

I am loathe to point out the error as it may simply give publicity to them, but there are 7 candidates for the Mayoral election, the BNP! Still at least you included the Independent candidate in your list, unlike the BBC who have chosen to feature six candidates not including Siobhan Benita