Medical tourism is not a one-way street. Research shows the number of patients travelling from the UK for treatment abroad is greater than the number coming to the UK. Johanna Hanefeld, Neil Lunt and Richard Smith looked at effects of health tourists on the NHS and uncovered a nuanced picture which has implications for debates around medical tourism, migration and health.

Medical tourism is not a one-way street. Research shows the number of patients travelling from the UK for treatment abroad is greater than the number coming to the UK. Johanna Hanefeld, Neil Lunt and Richard Smith looked at effects of health tourists on the NHS and uncovered a nuanced picture which has implications for debates around medical tourism, migration and health.

Recent public attention on immigration has included a focus on ‘health tourism’ – a term used to denote patients travelling to the UK with the expressed purpose of accessing treatment. It has extended to use of the NHS by recent immigrants and migrants.

In the context of wider discussion about migration, findings from our recent research on patient mobility are of relevance. We conducted a large study which looked at effects of medical tourism on the NHS. This involved a comprehensive look at the patients who travel and why. It included work looking at numbers of patients, costs arising from patients travelling, potential savings to the NHS and income from patients coming into the UK. Three specific findings seem particularly relevant in debates around medical tourism, migration and health.

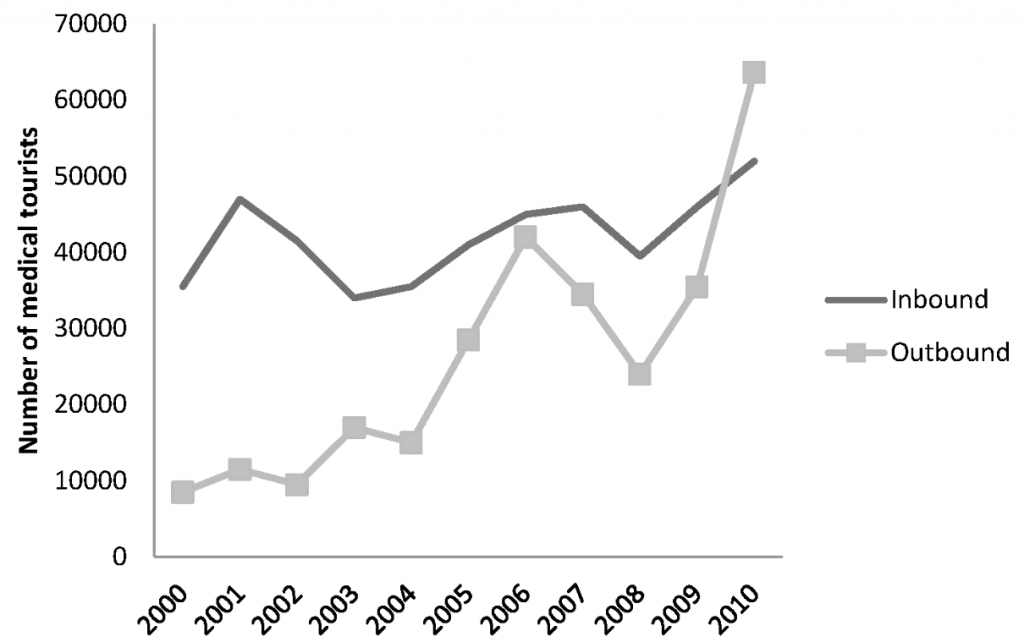

1) A growing number of UK residents travel abroad to access treatment. While there is a long and continuing history of patients from abroad travelling to the UK to seek medical treatment, including in the private sector and privately from the NHS. Analysis of the International Passenger Survey (IPS) suggests that the number of patients travelling from the UK to access treatment abroad is greater than the number of patients travelling to the UK to access treatment (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of patients travelling to and from the UK to access health treatment

Source: A Cost or Benefit to the NHS?

2) Patients who travel into the UK for private treatment in the NHS are likely to be more lucrative than private patients resident in the UK. Our analysis of private patient income in 27 NHS Foundation Trusts showed that almost a quarter of their private patient income resulted from non-resident patients, even though these only accounted for seven percent of patients.

3) Patients who travel experience complications. Many of the people we encountered in our research did not match the idea of an ‘empowered consumer’ or ‘tourist’ travelling for a cheap deal in an exotic destination. Many patients had experienced challenges in accessing treatment they felt needed. They were compelled to travel to seek better, more easily accessible or cheaper care abroad. In many cases this was a difficult decision and patients faced challenges, including complications and need for follow-up care. In terms of costs and benefits, it may still be cheaper for the NHS to ‘fix’ patients who have opted to pay for treatment privately abroad. However, there is an ethical dimension to this. There is no clear guidance or regulation for medical travel. Redress in cases of malpractice is often complex and costly to achieve, involving multiple jurisdictions.

These findings highlight several things: Medical tourism is not a one-way street. UK taxpayers travel to other countries for treatment and as a result they may displace the local population from its own health services, or use much needed local doctors and nurses who have been trained through the public system in the receiving country. We need to know more about the effects of medical tourism on health systems to have an informed debate about fairness and contributions, including in the context of foreigners’ use of the NHS.

Second, when thinking about raising private income in the NHS, patients travelling to the UK seem to be a particularly lucrative source of income. Further detail on tariffs and billing would provide more detailed information. Third patient mobility is not without risks, whether it is opportunistic, with intention to pay or in order to take advantage of services abroad. It is also currently unregulated. Given the evidence that patient mobility is increasing, this ought to be a policy priority.

Policymakers can learn from patients travelling. Outbound medical tourism from the UK tells us about the NHS: where it fails UK residents who have an entitlement to care and treatment and who feel failed by the system and risk complications by privately arranging to visit providers abroad, without regulation or clear safeguards.

For more on these issues read our paper Medical Tourism: A Cost or Benefit to the NHS?

Note: This article solely gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Dr Johanna Hanefeld is Lecturer in Health Systems’ Economics at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine where she works on health, trade and global governance.

Dr Johanna Hanefeld is Lecturer in Health Systems’ Economics at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine where she works on health, trade and global governance.

Professor Richard Smith is Professor of Health System Economics at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. From 2008-2011 he served as Head of Department of Global Health & Development, and since 2011 has served as Dean of Faculty of Public Health & Policy.

Dr Neil Lunt is Reader in Social Policy and Public Sector Management at the University of York.

Dr Neil Lunt is Reader in Social Policy and Public Sector Management at the University of York.

link to paper is not working

Thanks Harry. We’ve updated the link now.

If no. of cases are increased in one month percentage of commission will be increased. You don’t have to invest anything. you have to start marketing for your social circle or anything you like and look for patients who are interested in getting treatment from abroad.

If you are interested please let us know i can forward you copy of contract so that go through full terms and condition between each other.

Types of medical surgeries and treatment we cater:

Cardiac/Heart Treatments

Cosmetic Surgery

Orthopedic Treatments

Endocrinology

Dentistry

Ear & Hearing Aids

In Vitro Fertilization

Stem Cells & Immunotherapy

Endocrinology

Physiotherapy & Rehabilitation

Spine Surgery

Gastroenterology

If interested please provide your email address to start the process

Thanks

Harish Athotra

+919873073334

athotra@yahoo.com

YOu have considered inbound and outbound. What about domestic medical travel and it’s implications?