Wendy Jones argues that the government’s proposed changes to the school curriculum for maths contain serious flaws. Children need to become secure in their understanding of the basic mathematical concepts during their primary school years and this must be reflected in the teaching programmes.

Wendy Jones argues that the government’s proposed changes to the school curriculum for maths contain serious flaws. Children need to become secure in their understanding of the basic mathematical concepts during their primary school years and this must be reflected in the teaching programmes.

Ever since Kenneth Baker first introduced a National Curriculum for schools in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1988, governments have periodically had a bash at revising aspects of it. It’s one of those cyclical things. The business of defining what children should study and what they should know at different ages remains – some would say regretfully remains – as deeply political as ever.

The current government is at it again (although this time of course, post-devolution, it’s just schools in England at the receiving end). But this is a major overhaul, aimed at defining “the essential knowledge that all children should acquire”. In June, the Department for Education (DfE) published draft proposals for English, maths and science in primary schools. Secondary proposals are yet to come and there’ll be a full public consultation later on, but the organisation of which I am a trustee – National Numeracy – felt it was important to make our views known early on about one crucial area – maths. We’ve told Michael Gove that his department’s proposals contain serious flaws.

Let me take a step or two back here. Maths is a troubled subject within the school curriculum. Many children begin to lose interest around the half-way mark in primary school. (National Numeracy has started a project looking at this, with help from John Lyon’s Charity.)

By early secondary school, many have switched off altogether and maths is often the least popular subject on the timetable. In spite of improvements in recent years, 40 per cent still don’t get a reasonable GCSE pass (regarded by many as the minimum requirement for employability) and fewer than 20 per cent in England, Wales and Northern Ireland continue with maths beyond 16 – among the lowest rates in the developed world (See research by the Nuffield Foundation). Scotland does a little better, partly because of a different exam and curricular system.

The vicious cycle is obvious. Fewer maths students mean a smaller pool from which to fish for inspiring maths teachers (there is always a shortage of good maths teachers – ask any head teacher who’s been trying to recruit new staff for September). And that feeds back into the experience that children have in the classroom….

It also leads to a massive problem with adult innumeracy. Government figures published last year showed that nearly 17 million people – virtually half the working-age population in England – had numeracy skills below Level 1 (i.e., at the levels expected of children at primary school) and over three-quarters were below Level 2 (GCSE A*-C level). The position for numeracy had actually worsened since the last such survey eight years earlier, whereas that for literacy had improved. Yes, I know there is a discrepancy here between the increase in recent years in GCSE maths passes and the decrease in adult numeracy levels: young people’s greater success at GCSE should be feeding into the adult rates. What this says about the value of GCSE maths and the comparability of GCSE exams and adult numeracy tests is an area ripe for more research.

But what we do know is that many of the 17 million struggling with numeracy didn’t ‘get’ maths at school, found the subject difficult and/or boring and learnt to convince themselves that they couldn’t do it. That is why any suggestion that young people should be forced to do more of the same post-16 if they haven’t succeeded pre-16 needs very careful consideration.

The content of the curriculum is clearly only part of the problem here, but it is a significant part. What is taught links to how it is taught and the attitudes children develop as a result. And that brings me back to the government’s review.

National Numeracy is pleased that the DfE is paying close attention to the maths curriculum: improvements are needed. We also like some of the top line statements about mathematical reasoning and problem-solving. But these are not followed through in the details of the proposed teaching programmes.

We believe that children need to become very secure in their understanding of the basic concepts of maths during the primary school years and that, in order to ensure this, the curriculum should concentrate on the essential core. The government’s draft proposals don’t travel in this direction. They risk an overloaded curriculum, with little connection between the many separate ‘competences’ (not helpful either to children or to non-specialist teachers) and too much early dependence on abstract rote learning. We think that an expert group should be urgently formed to oversee the maths curriculum across the age range – even if that delays the curriculum review. (I realise the government has a political timetable to adhere to, so this idea may not be very well received. But it is offered in good faith and is worth considering.)

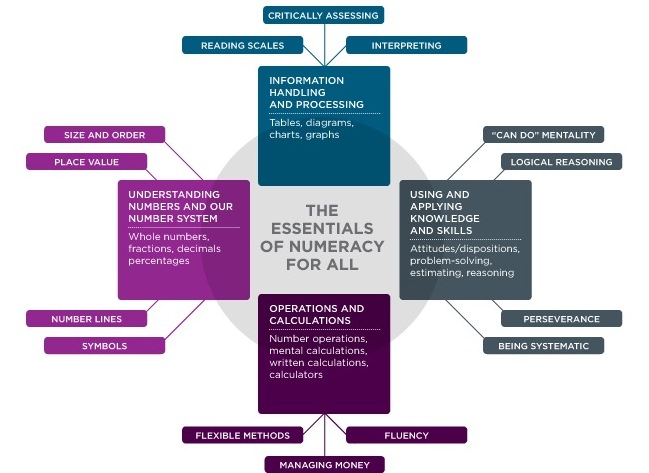

There is one point to clarify here – and some of the reactions to our response seemed to miss this point: numeracy is not just about arithmetic. We favour the OECD definition which, simplified, says that being numerate means having the understanding and confidence to use maths in everyday life – that is, being able to follow government statistics in the news, compare interest rates, read a pay slip. We’ve offered the government our model of the ‘essentials of numeracy’ – see here for details.

Yes, children should learn their tables. I had them drummed into me at primary school a long time ago and very useful they’ve proved too. But this should not be at the expense of understanding the mathematical concepts behind them. Having automatic recall of 9 x 7 makes life easier, but if it doesn’t also help you calculate 18 x 7, then a vital sense of mathematical pattern has been missed. Similarly, to work out the cost of seven apples at 30p, you’ve got to have a sense of number place value. To know that buying three items with a 30 per cent discount does not give you 90 per cent off in total means understanding the concept of per cent.

So where does this leave us? We know a large part of the mathematical community shares our views and has told the government pretty much the same. We know the school inspectors are worried that too many children increasingly fall behind throughout their school careers (see Ofsted’s recent report, Mathematics: made to measure). We believe the government would very much like to get it right, but we know also that there are political prejudices at play here (ministers are greatly drawn by the notion of ‘rigour’ and terrified by any accusation of dumbing down). This government now has a significant opportunity to do something effective. We shall see.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Wendy Jones is a founding trustee, frelance writer and former BBC education correspondent. National Numeracy was launched in March this year as an independent charity dedicated to improving levels of numeracy across the UK.