With repeated national polls estimating their support below 10 per cent, the Liberal Democrats put everything they had into winning the Oldham East and Saddleworth by-election, a seat where they had virtually tied with Labour in May 2010. Instead Labour has romped home convincingly. Chris Gilson and Patrick Dunleavy argue that the strains on the coalition have now increased, while the Labour leader Ed Miliband has passed an important milestone.

With repeated national polls estimating their support below 10 per cent, the Liberal Democrats put everything they had into winning the Oldham East and Saddleworth by-election, a seat where they had virtually tied with Labour in May 2010. Instead Labour has romped home convincingly. Chris Gilson and Patrick Dunleavy argue that the strains on the coalition have now increased, while the Labour leader Ed Miliband has passed an important milestone.

For the last forty years, by-elections have gladdened the hearts of Liberal Democrat activists and leaders. By allowing them to mass their limited resources into a single seat, for once they can compete on even terms with their larger rivals. And by prominently focusing on local issues instead of the national debates at general elections, and creating a local whirlpool of momentum pulling people into tactically voting for them, the party has always been able to walk tall in the by-election context.

The contest in the Oldham and Saddleworth constituency also took place in favourable circumstances, where Clegg’s candidate at last year’s the general election had virtually tied in vote share with a Labour ex-minister (Phil Woolas). When Woolas was subsequently turfed out of Parliament by an election court for telling lies about his opponent in his campaign, the Liberal Democrats should have been in a good position to win. Finally, Oldham showed fairly balanced three party competition in 2010, meaning that the Liberal Democrats should have been able to benefit from some amongst the large mass of Tory supporters coming over to them tactically in order to beat Labour.

But in government, and blamed for the onset of austerity cuts and policy betrayals over student fees, none of this helped the Liberal Democrats at all, as our Table below shows. Voters in Oldham stubbornly refused to get energized by the massive Liberal Democrat influx of activists, and the eventual turnout was a dismal 48% (down from 62% last year). The Conservatives barely campaigned in order to help their partners, and the Tory vote duly collapsed towards the Liberal Democrats, with half their support (13 per cent of the votes) moving across.

None of this helped Clegg’s candidate though, because a huge raft of former Liberal Democrat supporters deserted to Labour, whose vote share soared ten percentage points. Interestingly support for the far-right BNP was maintained, while UKIP slightly increased their vote share. The Greens campaigned in this constituency for the first time and accumulated a small vote.

Table: The elections in Oldham, June 2010 and January 2011

| Party | % votes general election | % votes by-election | Change |

| Labour | 32 | 42 | +10 |

| Liberal Democrats | 32 | 32 | +0.3 |

| Conservative | 26 | 13 | -13 |

| UKIP | 6 | 6 | +0.1 |

| BNP | 4 | 4.5 | +0.5 |

| Greens | 0 | 1.5 | +1.5 |

| Four other candidates | 0.5 | 1.1 | +0.6 |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

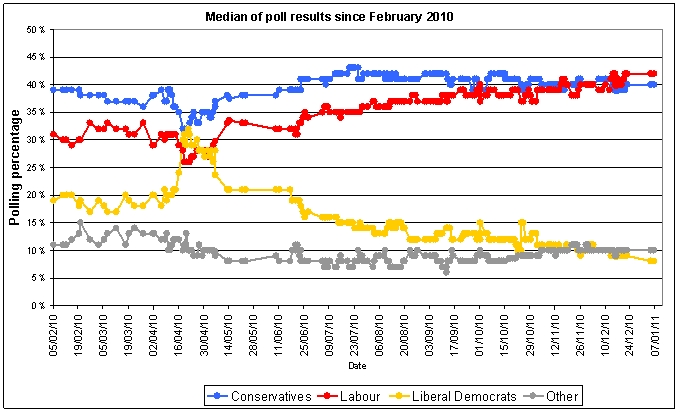

Setting this result against the broader trends in opinion polls since the general election shows the Liberal Democrats sinking dramatically below the combined support for the ‘Other’ smaller parties, into territory that could mean the party being almost eliminated in terms of Westminster representation. The by-election, real votes in a favourable contest, is especially toxic for the Liberal Democrat spin doctors who have repeatedly pointed to their support holding up in local authority by-elections as evidence that the national polls were not capturing what people really felt. This whole rationalization has disappeared in a puff of pink smoke.

The scale of the Liberal Democrats decline is now hugely magnified by the spike of Clegg-mania during the general election campaign. But it is the steady seepage away in the last two months that is really risking cooking the Liberal Democrats’ goose. As of early December 2010, 60 per cent of poll respondents felt that Nick Clegg was doing badly, and only 31 per cent thought he was doing well – hardly surprising considering his party’s low poll ratings. Yet Clegg personally is also strongly and personally criticised for siding with the Conservatives and most acutely for breaking his parties’ manifesto promises on tuition fees.

Meanwhile for Ed Miliband, still batting himself in carefully as Labour leader and surrounded by disgruntled Blairites mourning the loss of his brother (the former heir apparent), the Oldham result is a useful buttress against his preposterously premature critics. Miliband has a realistic appreciation that around a quarter of the British public still do not fully know who he is or what he stands for, and they will not do so for many months still ahead. Our chart below shows that he attracts more than twice as many ‘Don’t know’ responses voters compared with those for David Cameron or Nick Clegg. But it was ever so for new and untried leaders in British politics, although Miliband’s net dissatisfaction score is somewhat more worrying for an opposition leader. Achieving a first concrete success is likely to improve his ratings though.

Source: politicalbetting.com

Finally, David Cameron is enjoying a narrow margin of net support, with 47 per cent thinking he is doing well as Tory leader and 45 per cent disagreeing. The collapse of the Conservative vote in Oldham, contrasting with the stable support for the farther-right parties (UKIP and BNP) will be read by the PM’s critics on the Conservative right as evidence that Cameron’s coalition strategy is endangering their party’s base of support, despite the Tories’ generally buoyant but flat ratings shown in our opinion poll chart above. The arch Eurosceptic Tory grandee Lord Tebbit urged Oldham voters to back UKIP in protest at what he perceives as Cameron’s snuggling up to Europe. So the internal strains within the Conservatives’ ranks are still multiplying slowly beneath the surface.

What could all this mean in general election terms? Assuming that the national opinion polls have it right, then the Liberal Democrats could have fewer than 10 MPs left in a general election held under first past the post and the current constituencies. Labour would have a small majority in the Commons of around 20 seats, albeit with the Conservatives running them close still. Nor would shifting to the Alternative Vote system change this result significantly.

Click here to respond to this article.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Two facts about the Oldham by-election that commentators fail to mention. First, no government party has (to my knowledge) won a by-election in almost 20 years. In other words, by-elections are side-shows and poor predictors of future elections especially this early into a new parliament. Second, in explaining the collapse of the Conservative vote in Oldham the media and commentators never mention the fact that the Tory candidate – a second-generation British Asian – was trying to contest a seat in a constituency where the worst racially motivated riots in the UK took place 25 years ago.