The true extent of party leaders’ influence on the way individuals vote needs to take into account election-specific evaluations of political parties as well, says Anthony Mughan. Among other conclusions on the dynamics of leader effects, his research finds that partisans are more likely to defect to another party when, in the election, they like that party’s leader more than they like their own party.

The true extent of party leaders’ influence on the way individuals vote needs to take into account election-specific evaluations of political parties as well, says Anthony Mughan. Among other conclusions on the dynamics of leader effects, his research finds that partisans are more likely to defect to another party when, in the election, they like that party’s leader more than they like their own party.

Britain is once again in the throes of a closely fought general election contest and, as has been the norm in recent campaigns, much of the media coverage revolves around the leaders of the parties. Their character traits, leadership records, prime ministerial potential and political strengths and weaknesses all undergo close scrutiny.

It is now commonly accepted that party leaders can be important influences on the way individuals vote and the way elections turn out. But ironically for a parliamentary system in which party was once seen as the driving force behind election dynamics, the true extent of their influence may have been underestimated by the uniform failure of existing psephological research to take account of election-specific evaluations of political parties as well as their leaders.

To be sure, despite the new-found electoral impact of parliamentary party leaders in Britain and elsewhere, the role of parties in the electoral calculus of voters is far from ignored by psephologists, but it is over-simplified and under-estimated. That is, the total impact of parties on the vote in any election is commonly assumed to flow solely through voter’s long-term partisan loyalties, or party identification. This is a psychological attachment to a political party that is durable across time, highly resistant to change and largely unaffected by the specific circumstances of a particular election contest. For the Conservative party to veer to the right in a particular campaign (under Margaret Thatcher in 1983, for example) does not mean that left-leaning Tory identifiers will cut their ties with the party. They may like it less for changing tack and may even contemplate not voting for it in that election to register their disapproval, but this is an altogether different reaction than disavowing their long-term allegiance to it.

Against this background, the overwhelming norm in the study of leader effects in parliamentary elections is to ask voters how much they like the individual party leaders (scoring each of them between 0 and 10 on a scale ranging from dislike to like). These evaluation scores are then entered into some kind of regression equation along with a number of control variables, including party identification as well as other standards like age, education, gender, social class and perceptions of personal and national economic fortunes. An individual party leader is then concluded to be an electoral assets to her party to the extent that her evaluation score passes the threshold of statistical significance. Thus, the party leader is seen as an electoral force in her own right and evaluated on her own merits with an electoral impact that is unrelated to voter evaluations of other political actors in the campaign.

Doubts about this conceptualisation of the electoral influence of party leaders can be raised on two fronts, however. One, it runs directly counter to the traditional view that political parties are the driving force of parliamentary election dynamics. Two, it does not allow for the cross-pressures felt by, for example, the Conservative identifier who likes Tony Blair a lot more than the Labour party precisely because of his efforts to move the party he leads to the political centre. Similarly, there is the case where a left-leaning Tory does not like the direction her party has taken under David Cameron and who, in the 2015 election, likes the Labour leader, Ed Miliband more for the direction in which he proposes to take the country.

How are such cross-pressures resolved? One possibility, of course, is that the voter feels no such cross-pressures and, as is now commonly thought, is moved by leader evaluations alone. Another is that the identifier simply sublimates his admiration for the opposition party and its leader and votes for his usual party in the election. Yet another is that the identifier rejects her party in the election, succumbs to her attraction to the other party’s leader and votes for that party.

Using the 2005 British Election Study, an analysis was undertaken to choose between these scenarios. Three models of leader effects were constructed. Model one hypothesised voters to react just to party leaders, Model 2 saw them voting for a party other than the one with which they identify when they liked that party’s leader more than his party and, finally, Model 3 saw them as defecting to a party with which they did not identify when they liked that party’s leader more than they liked their own party. In other words, in question was whether election-specific party evaluations play a role in determining the magnitude of leader effects or is their magnitude, as is commonly supposed at the moment, simply a function of election-specific leader evaluations.[1]

A number of conclusions followed. First, Model 2, the comparison between other parties and their leaders has no effect on the likelihood of partisan defection. That is, even if loyalists like another party’s leader more than they like his party, they are no more likely to defect to it.

Second, Model 1 does offer some explanation of partisan defection in parliamentary elections. It shows that, as the current literature on leader effects would predict, partisan defection to another party is more likely the more identifiers with a party like that other party’s leader.

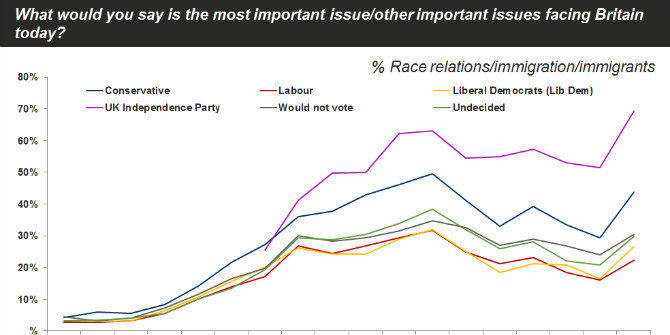

The final, and most striking, conclusion, though, is that leader effects are at their strongest by some margin in Model 3. That is, partisans are more likely to defect to another party when, in the election, they like that party’s leader more than they like their own party. Thus, assuming that these findings are generalizable beyond the major parties (Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat), we have the intriguing scenario in 2015 that the Tories will be especially likely to lose votes to UKIP when the party’s identifiers like Nigel Farage more than they like the Conservative party on offer to them in this campaign. This scenario would seem less likely for Labour identifiers so that UKIP would again seem to be an asymmetrical threat to the two major parties’ vote shares.

By way of final observation let me note that this pattern of findings does not seem to be idiosyncratic to Britain with its low levels of popular identification with the major parties. Rather, very much the same pattern is found in Australia with its relatively high levels of partisan identification. The simple conclusion would seem to be that leader effects in parliamentary elections are strongest when parties are rehabilitated and election-specific evaluations of them are factored into voters’ electoral calculus along with election-specific evaluations of their leaders.

This article is based on “Parties, conditionality and leader effects in parliamentary elections” by Anthony Mughan in the Party Politics journal.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: UK parliament (parliamentarty copyright).

Anthony Mughan is Professor and Director of International Studies in the Department of Political Science, Ohio State University.

Anthony Mughan is Professor and Director of International Studies in the Department of Political Science, Ohio State University.

[1] A fourth model comparing leader evaluations was tested and it was derived by subtracting one leader’s score from the other’s. It produced results that were almost indistinguishable from those generated by entering the leader evaluation scores into the estimation equation separately and is therefore not discussed in the text.

The problem with regression modelling in political “science” is that there is no guarantee that the future will be like the past. Nor can such a model offer any insight into why – to take an obvious example – a Tory leader with “heartland” values should be so successful in the 1980s but not since.