Michael Rush explores the extent of participation in Parliament by party leaders. He finds that the role of the Prime Minister, as well as that of the Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Liberals/Liberal Democrats, have become largely institutionalised. Other party leaders are much more active as they also have to work harder to gain attention.

Michael Rush explores the extent of participation in Parliament by party leaders. He finds that the role of the Prime Minister, as well as that of the Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Liberals/Liberal Democrats, have become largely institutionalised. Other party leaders are much more active as they also have to work harder to gain attention.

Research by Patrick Dunleavy and his colleagues showed a clear decline in prime ministerial activity at Westminster, as measured by their participation in debates and answering parliamentary Questions. That decline has not been reversed, although the institutionalisation of Prime Minister’s Question Time has meant that the number of Questions answered orally by the Prime Minister has become formulaic.

However, Dunleavy et al did not cover other forms of parliamentary activity, such as Questions tabled for written answer, the tabling and signing of Early Day Motions (EDMs), committee work, and voting in divisions. Nor did they examine the parliamentary activity of other party leaders. For much of the period they cover – from 1868 – other party leaders meant the Leader of the Opposition, the Leader of the Irish Nationalists until 1918 and, from 1900, the Leader of the Labour Party, until Labour supplanted the Liberals and the latter slipped into third party status. But from 1974, third parties became increasingly prominent, with the rise of Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party and the fragmentation of parties in Northern Ireland.

Two questions therefore arise. First, is the participation of Prime Ministers in debate mirrored in other forms of activity? And second, do other party leaders behave in much the same way as Prime Ministers in their parliamentary activity? An answer to these questions can be found by analysing the parliamentary activity of all party leaders since 1945.

It is hardly surprising to find that, in spite of making more statements in the House of Commons – the result of the UK’s membership of the EU and of other international bodies leading to Prime Ministers attending more summit meetings – prime ministerial activity has remained at much the same level as Dunleavy et al found. Of course, there are some parliamentary activities in which Prime Ministers do not engage, such as tabling Questions, tabling or signing EDMs, and committee work, but which are open to other party leaders.

The parliamentary activity of the Leader of the Opposition and the Leader of the Liberals/Liberal Democrats, however, tends to be very similar to that of Prime Ministers. Both have similar contribution levels in debates to Prime Ministers, while they table few Questions for written answer, and do not participate in committee work. Moreover, they normally limit their use of EDMs to the procedural device of ‘prayers’ against statutory instruments, only rarely tabling or signing EDMs. However, they do vote more often than Prime Ministers. Of course, there are variations in their activity: Clement Attlee was famously terse, Neil Kinnock famously verbose; and Michael Howard more active than William Hague before him or David Cameron after him, and Gordon Brown more active than Tony Blair. Variations can also be found where the same individual has held the same post more than once, as Harold Wilson illustrates. Writing of his role as Prime Minister in 1964, after Labour had been in opposition for thirteen years, and again in 1974, after Labour experienced government between 1964 and 1970, he says:

‘In the 1964 government…I had to occupy almost every position on the field, goalkeeper, defence attack – I had to take corner-kicks and penalties, administer to the wounded and bring on the lemons at half-time. Now…I would be no more than what used to be called a deep-lying centre-half…concentrating on defence, initiating attacks, distributing the ball and moving up-field only for set piece occasions.’1

Analysing Wilson’s two periods as Prime Minister supports this account: he was markedly more active in debates between 1964 and 1970 than between 1974 and 1976, although Wilson’s declining health was a factor. He was also more active in his first period as Leader of the Opposition from 1963 to 1964 than during his second between 1970 and 1974

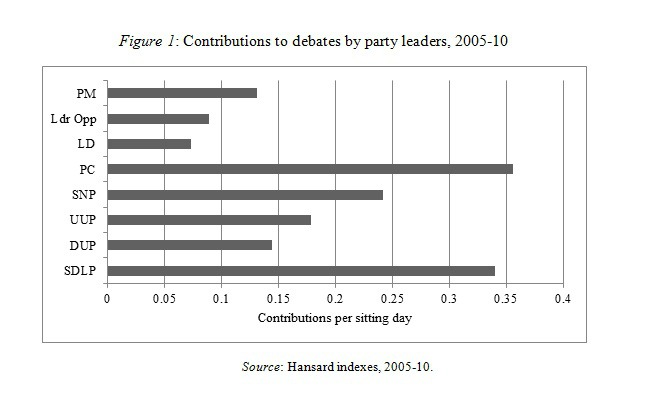

In contrast, other party leaders present a very different picture, although they too are not normally involved in committee work. In all other activities, however, they are much more active: they ask more Questions for written answer, table and sign more EDMs, and vote in divisions more often. This can be illustrated by one example – contributions to debates in the 2005-10 Parliament.

Not surprisingly, as with the leaders of the three major parties, the leaders of other parties also differ in their levels and types of activity. Alex Salmond, for instance, was the most active such leader in contributions to debates. Elfyn Llywd, parliamentary leader of the Plaid, and Mark Durkan, SDLP Leader, both made considerable use of EDMs and Angus Robertson was the greatest user of Questions for written answer.

The contrast between Prime Ministers, Leaders of the Opposition, Leaders of the Liberal Democrats, on the one hand, and the leaders of other parties, on the other, is clear, but what is the explanation? The answer appears to be that the roles of the Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Liberals/Liberal Democrats have become largely institutionalised in that both behave like behave like putative Prime Ministers. Some Leaders of the Opposition have served as Prime Minister, others go on to do so, but, even when the Liberals/Liberal Democrats have had so few MPs that it was suggested that they could all share a single taxi, their Leader retained the status in the Commons of the leader of a major party, and by convention was treated so procedurally.

In contrast, the other party leaders lack that status and therefore have to work harder to get themselves heard. This means that their parliamentary activity is more varied and also varies more between different leaders of the same party. The willingness of the leaders of other parties to engage in a range of parliamentary activities is also illustrated by their participation in Westminster Hall debates since they were set up in 1999, opportunities almost entirely eschewed by the Leader of the Opposition and the Leader of the Liberal Democrats. In short, the activity of the leaders of other parties has not been institutionalised in the same way as that of the leaders of the bigger parties has and they feel less constrained, they also have to work harder to gain attention.

This post is based on an article ‘Engaging with the enemy: the parliamentary participation of party leaders, 1945-2010’ published online in Parliamentary Affairs. ref.: doi: 10.1093/pa/gss095.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Michael Rush is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Exeter.