The centre-left is still missing a popular critique, particularly on the economy, writes Tim Bale. Picking up on populism may be playing with fire but, done carefully and, dare one say, responsibly, it could very well do social democrats more good than harm.

The centre-left is still missing a popular critique, particularly on the economy, writes Tim Bale. Picking up on populism may be playing with fire but, done carefully and, dare one say, responsibly, it could very well do social democrats more good than harm.

Interviewed by the BBC in late December 2013, the UK’s Business Secretary, the Liberal Democrat politician Vince Cable, poured a mixture of doubt and scorn on Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron’s proposal to reduce the entitlement of EU citizens to come and live and work in Britain. But he also confessed he was not entirely surprised. ‘There is a bigger picture here’, he told his interviewer. ‘We periodically get these immigration panics in the UK. I remember going back to Enoch Powell and the ‘rivers of blood’ and going back a century there was panic over Jewish immigrants coming from Eastern Europe. The responsibility of politicians in this situation when people are getting anxious is to try to reassure them and give them facts and not panic or resort to populist measures that do harm.’

Politicians on the right were quick to condemn what one of those Tory MPs leading a rearguard action to persuade the government not to lift restrictions on Bulgarians and Romanians, called Cable’s ‘ridiculously over the top and ill-judged remarks’. Privately, however, there may have been some sympathy with his views. Tory modernisers may be something of an endangered species these days but the tone of some of their party’s talk on the issue must surely have grated if not dismayed.

Meanwhile, neo-liberals – at least those who haven’t yet allowed their Euroscepticism to trump their enthusiasm for the market – must surely worry about fettering free movement in what they themselves like to think of as ‘a global race.’

Finally, those with even the faintest familiarity with twentieth-century British history may have blanched at Cable’s mention of Enoch Powell, but would have had to agree with his point that public concern over immigration is not merely a function of numbers but is also primed by politicians and the press and that it therefore tends to move in cycles: hysterical in the early 1900s, rising again in the late 1950s, rumbling on (and off) until the late 1970s, then dropping in the 1980s and 1990s, until the panic over asylum and massive labour migration from the accession countries kick-started it again at the turn of the century.

Cable’s fellow Liberal Democrat ministers were more supportive than many might have imagined: this time, it seems, the Tories really may have gone too far even for Clegg and co. Labour’s reaction, however, was even more interesting. Shadow Home Secretary, Yvette Cooper, clearly decided it was better not to intrude on family grief by mentioning Cable specifically, but was quick into print to predict that what she called the government’s ‘frenzy of briefings on immigration’ wouldn’t work, claiming that the ‘last minute rush and ramped up rhetoric looks more like panic than plan’. Rather than ‘chasing headlines that increase concern and hostility,’ she suggested, ‘David Cameron should concentrate on sensible policies to help.’ Labour, she added, wasn’t about to ‘join a Dutch auction of tough language that helps no one.’

To many of those who followed the twists and turns of migration and asylum policy under the last Labour government, when headline-chasing briefings on both issues were regularly accompanied by ramped-up rhetoric, her words may provoke an ironic smile. But they should surely also provide a measure of reassurance. Her main point, after all, was that her party was determined not to strike poses but at the same time was prepared to admit that it ‘got some things wrong on immigration in government’ – in particular on transitional controls and on the impact the huge number of East European migrants who came to the UK after 2004 had on public opinion and on low paid workers. Labour, she assured readers, had ‘listened and learned.’

But to and from what – or whom? While the economic arguments over the pros and cons of mass immigration were (and are) more finally balanced, a simple reading of any poll published this millennium could have told Labour politicians, when they were still in office, that they were on the wrong side of an increasingly anxious electorate. Yet that was insufficient either to persuade them to admit their mistakes or to prevent them, at least in Gordon Brown’s case, from resorting to rhetoric – ‘British jobs for British workers’ – apparently more redolent of the BNP than a serious political party. Surely something else must have happened in the meantime to prompt the new approach?

Losing power inevitably made a difference. So too did the economic downturn. It’s one thing to read that people responding to opinion polls say they don’t think much of you or your policies, but it’s quite another for them to vote you out of office. And what happened after 2007 – and, indeed, what happened to real wages at the lower end of the income distribution even before then – has given lots of Labour people pause for thought. Just as allowing the financial and property markets to let rip in return for a share of their revenues no longer seems like social democracy in action, nor does allowing in huge numbers of migrants to help turbo-charge growth without stoking inflation.

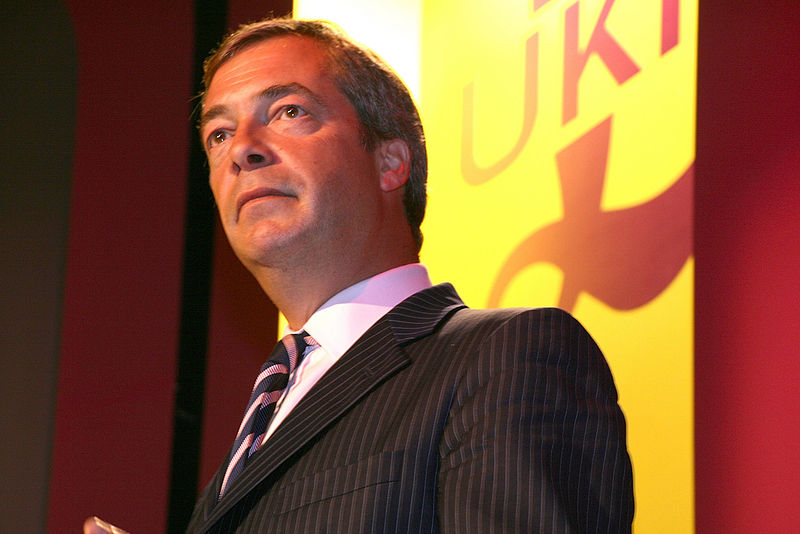

Farage’s favours to Labour

Yet something important is still missing if we want to explain Labour’s conversion to a more restrictive immigration policy but one couched in more restrained rhetoric. That something is the populist critique – the notion that politics-as-usual conducted by a self-satisfied elite which presumes to know what’s good for us, has to undergo fundamental change if democracy is to deliver what people really want. Practically woven into the DNA of Britain’s tabloid press, and flirted with by almost every Tory leader since Benjamin Disraeli, it has, since 2010, gained new momentum and resonance after being picked up and run with by UKIP under Nigel Farage. So much so that a critique whose appeal to ‘common sense’ and charisma have indelibly associated it in continental Europe with the insurgent extreme has now become part of mainstream politics in the UK.

But it’s not just by helping to persuade Labour to take some of the drawbacks of mass migration more seriously that Farage has done the Party a favour. For one thing, by causing the Tories to panic about his eating into their vote, he has pushed previously liberal Conservatives like David Cameron and Theresa May into adopting measures and rhetoric in government that would have horrified them in opposition – measures and rhetoric which alienate the well-heeled, well-educated voters they were once so keen to want to win back at the same time as failing miserably to convince the rest of the electorate that they really mean it like Nigel means it.

Clearly, the Tories were ill-advised to promise such a huge reduction in net migration in the first place. But, having done so, they should have stuck to their guns rather than undermining the very real progress they have (rightly or wrongly) made by taking second, third and fourth bites at the cherry, thereby sending the message that what they’ve done up till now isn’t nearly enough. This is a lesson for Labour, and one that probably applies just as much to crafting its line on welfare as its line on immigration. By all means listen to and learn from the populist critique. Even meet it half way. But half way is far enough. Any more than that you end up in a race that you can never win and overpromising and under-delivering rather than, as it should be, the other way around.

The other favour Farage has done Labour is to help it rediscover its own penchant for populism. It is easy to forget that even in 1997, Labour achieved its victory not just because it trespassed into supposedly Tory territory by promising to be ‘tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime’ but also because it stood for a Britain ‘where merit comes before privilege, run for the many not the few’, in so doing echoing its promise in 1945 to ‘win the Peace for the People’ and its pledge in 1964 ‘to provide the whole people with the high living standards, the economic security, and the cultural values which in previous generations have been enjoyed by only a small wealthy minority’ – one represented by the irredeemably ‘grousemoor’ politicians of its Tory opponents.

Labour’s popular appeal on the economy

The current crop of Conservatives and their friends in the media will of course dismiss all this as ‘left-populism’, typical of a party being led back to the seventies by ‘Red Ed’. Moreover, there are, as Roger Liddle has pointed out, some genuine risks involved: a party needing to rebuild its credibility and reputation for economic competence can’t afford to forget the difference between keeping it simple and sounding simplistic; it also needs business on its side rather than feeling sore at being branded a special or vested interest. And that’s just in opposition. In government, to return to a theme we’ve already touched on, both Harold Wilson and Tony Blair, like French President François Hollande more recently (and more swiftly), paid a price for encouraging expectations they could never realistically meet.

Sometimes in politics the pendulum can get stuck. Populism can help get it swinging again. Inevitably, however, it also has the potential to make that pendulum swing too far the other way. We may have reached that point on immigration – and on welfare too. When it comes to the economy, however, there is probably some way to go, particularly given the lack of serious structural change and sanctions that the financial meltdown of 2007 onwards has occasioned in the private, if not the public, sector – something that many voters have noticed even if some of their representatives haven’t. Picking up on populism may be playing with fire but, done carefully and, dare one say, responsibly, it could very well do the centre-left more good than harm.

This essay first appeared on Policy Network. It is a contribution to a new Policy Network and the Barrow Cadbury Trust project on ‘Understanding the Populist Signal‘. The author will speak at the project launch event in London on 6th February

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Tim Bale is professor of politics at Queen Mary, University of London.

Tim Bale is professor of politics at Queen Mary, University of London.

As Milton Friedman – a believer in free markets if ever there was one – is supposed to have said “You can have unrestricted immigration from poor to rich countries. Or you can have a welfare state. But you can’t have both.” As long as recent immigrants are entitled to social benefits, opposing unrestricted immigration is entirely consistent with free market views.