The police were not spared the axe in last year’s Comprehensive Spending Review, with 20 per cent budget reductions predicted. In the wake of August’s riots in England, police funding is now more relevant than ever. Blair Gibbs of Policy Exchange argues that massive amounts of extra funding have been poured into the police in the last 10 years, increasing officers by 15 per cent and civilian staff by 73 per cent, and that despite these increases we have not seen a significant rise in police performance, productivity, or in the public’s perception of their effectiveness.

The police were not spared the axe in last year’s Comprehensive Spending Review, with 20 per cent budget reductions predicted. In the wake of August’s riots in England, police funding is now more relevant than ever. Blair Gibbs of Policy Exchange argues that massive amounts of extra funding have been poured into the police in the last 10 years, increasing officers by 15 per cent and civilian staff by 73 per cent, and that despite these increases we have not seen a significant rise in police performance, productivity, or in the public’s perception of their effectiveness.

Policy Exchange’s new report – Cost of the Cops – released yesterday, was widely reported, partly for the suggestion that the Metropolitan Police should enhance visibility by asking officers to wear their uniform from home to station if they are claiming free public transport (worth up to £5,000 per year). The real focus of the report however, is on the larger issue of police funding, and what the huge increases since 2001 have delivered.

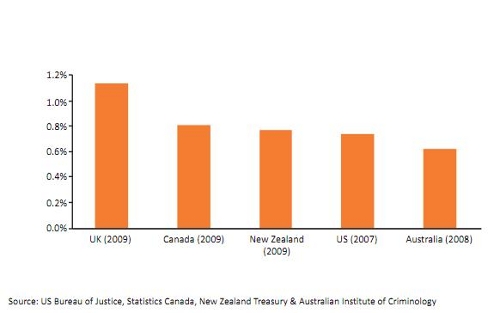

The backdrop to the current debate around police funding is clear: the police service in England and Wales has never been better resourced. The last decade has seen an unprecedented rise in police expenditure: reaching more than £14.5 billion – up 25 per cent in real terms. In 2010, each household was paying £614 per year for policing, up from £395 in 2001. Policing in England and Wales is also among the most expensive in the developed world – higher than the USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

Figure 1: Policing Expenditure as a percentage of GDP

Source: Cost of the Cops, Policy Exchange 2011

Most of the money went on people and led to unprecedented recruitment. Total police officer strength rose 15 per cent from 123,476 to 141,631, and there was a large increase in the number of civilian staff (made up of police staff, PCSOs, Designated Officers and Traffic Wardens), who increased 73 per cent from 57,104 to 98,801 over the decade. There are now 7 civilian staff members for every 10 police officers. If the police were a single company, they would be a significantly bigger employer than Tesco Plc in the UK.

Cuts in the next four years are challenging but not excessive

In this context budget reductions over the next four years will be from a high base and in this regard, policing in England and Wales is in a comparatively strong position: more officers than ever before, better supported by historically high numbers of civilian staff and new technology, and facing reduced crime demand after more than a decade of reductions in volume offences (as measured by the British Crime Survey).

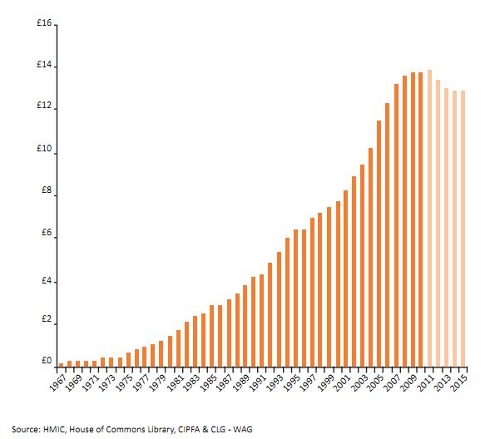

The reductions planned for 2010-15 are large historically, and they will be challenging, but they are not excessive. The 20 per cent budget reductions from the 2010 high amount to 14 per cent over four years once local funding is taken into account. Viewed in context, they do no more than reduce annual police funding to the level that would have been reached in 2015 if the trend rate of growth 1979-2001 had continued. The expansion after 2001 took police funding far higher than the trend increases of previous decades, and the funding agreed in the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review will act to correct this unprecedented “surge”.

Figure 2: Police revenue expenditure (£bn) 1967-2015

Source: Cost of the Cops, Policy Exchange 2011

By the end of the period (2014-15), we will still be spending more than £12 billion on policing each year, or £500 per household in England and Wales – more than what was spent in 2004 and £100 more than was spent in 2001 when funding was £9 billion. It is certain that police forces will be smaller in 2015 than they were in 2010. Even after the personnel reductions planned by forces up to 2015 there will still be 210,000 police employees in England and Wales – the same number as at March 2004.

What was the return on the investment?

Additional expenditure on policing should have delivered a sizeable return in operational performance and it is not clear that it has. In fact it is likely that an unprecedented growth in police posts in the last 10 years has delivered diminishing returns; driven an unsustainable increase in the police wage bill; and has not markedly improved police performance, which in some areas and on some measures has actually deteriorated.

There has been no robust analysis of whether the general increase in police resources delivered reductions in crime. However, we can state that the fall in BCS crime that began in 1995 preceded the large increases in police expenditure (and increased officer numbers). In fact total crime fell by 68 per cent before officer numbers increased after 2001 which means the majority of the fall in total BCS offences (1995-2011) was not the direct result of increased police resources.

Additional police officers undoubtedly helped reduce crime in some categories but an increase in police numbers cannot take the credit for crime falls during this period – most of which would have happened without the one-third real terms increase in police funding.

Detection rates are a key indicator of police performance, providing an indication of the likelihood that a case will be solved. The investment in more police officers ought to have enabled the police to take action against more offenders, especially as the number of reported offences (and therefore the pool of suspects) was gradually shrinking. But between 2001 and 2010 there does not appear to have been a clear translation of more funding into an improvement of detection rate. The national headline detection rate has only risen modestly – from 24.4 per cent in 2001 to 27.9 per cent in 2010 – and yet the costs of investigation for key offences has jumped dramatically.

Despite heavy investment in both police officers and civilian staff, these factors – indeterminate impact on crime and poor performance on detections – support the conclusion of the Audit Commission’s latest assessment that: “there is no evidence that high spending is delivering improved productivity”. The primary reason for this being the ineffective deployment of officers over the last decade, and the pursuit of the “numbers game”.

Instead of any systemic profiling of need or impact analysis, funding over this period increased because there was a political consensus, which was lobbied for successfully by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO). The political consensus that supported an increase in police budgets and officer numbers during this period rested on a simplistic assumption that never received adequate scrutiny – namely, that officer numbers alone are a good proxy for police performance and the more officers a force had, the better they would perform against crime.

When resources were flowing into the service, the political drive to hire more officers was not questioned – either within the service or externally. Yet in 2011, in evidence to a Commons Committee exploring the police spending and the impact of budget reductions, the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police identified the issue:

[There has been a] political obsession with the number of police officers. We’ve kept that number artificially high. Had large numbers of police officers doing admin jobs.

Did the police become more visible?

Between 2003-04 and 2007-08 forces were required to produce activity-based costing data for a range of police activities. Analysis of these figures reveals that for the period in which data was available, the majority of police forces shifted their resource spend away from visible patrol, with some forces reducing annual spend on visible patrolling over this period by an average of up to 15 per cent.

The historic investment in additional police funding and the net increase of 18,155 officers between 2001 and 2010 has not transformed public perceptions of police availability or performance. On officer numbers, it is almost as if the investment never happened. A new survey conducted by YouGov for the Cost of the Cops report suggests the public did not see a benefit comparable to the investment made.

Half of those surveyed thought there were either the same number of police, or fewer police, than in 2000. When asked if there are more police on the street than there used to be, a majority (58 per cent) disagreed, just 17 per cent agreed. The same YouGov survey asked about public attitudes to the service the police deliver, and whether it represented value for money. When asked if £600 per household per year for policing represented good value for money or poor value for money, half (51 per cent) said poor value, and a third said good value (36 per cent).

The survey results demonstrate that there remains a clear gap between the additional resources put into policing and the service received by the public. Most of the additional officers were not even noticed by the public, and a majority of people think there remain less police on the street than there used to be – highlighting ongoing concerns about visibility and availability.

The additional resources were not tied to reforms to pay or modernized working practices, and so the police organisation remained monolithic – growing in size but not become more flexible or efficient with its staff. Our analysis has shown that there are at least 7,280 officers who are doing roles that should be being done by civilians, and at significantly lower cost (a warranted officer is a police force’s most valuable asset, absorbing significant upfront recruitment and training costs and they are on average 60 per cent more expensive that civilians). This misdeployment of 1 in 20 of all officers is costing forces at least £147 million every year.

Getting More for Less

To ensure an effective service with reduced resources over the next four years will be challenging – but how policing performs depends upon how those more limited resources are used, and this requires a focus on delivering more for less so that as police budgets – and officer numbers – fall in the years ahead, forces maintain and where possible enhance police visibility, which should be a key priority for forces.

Police forces should look beyond the current CSR period (up to 2015) and plan for a decade of smaller increases in police funding from central government and a smaller total workforce. Forces should put emphasis instead on the case for growing local funding sources, expanding the police family and improving the productivity of the staff and officers hired in recent years.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Wow! Where does one start? How about at the comparisons? The USA, for instance, has a very different system for policing and is not comparable in any way. The other countries, Canada, New Zealand and Australia have different policing needs due to size and population. What has GDP got to do with the size of police forces in any case? Apart from showing the English/Welsh police in a bad light that is.

A much more sensible, and telling comparison would be with countries that have similar policing problems to the UK, such as Germany, France, Italy, Spain. Missed them, did you Blair old chap? Further, the article completely ignores demand, both on police time and resources.

I was involved in the planning for IT upgrade for command and control. It was the biggest single capital expenditure programme the force had ever seen, and it was just about as basic as we could get. We even went with an experimental one as it was cheaper and the company promised support. Which they delivered.

One better comparison might be the number of phone calls to the police from 1975 until today. Put that in your graph. There are more call takers/controllers in one of the call centres in my old force that there were in the whole of the MPD in 1975. Even so, they have been hit by the cutbacks and consistently fail to reach the targets.

Then there was the Police and Criminal Evidence Act which was not funded, apart from a few extra police officers. This eventually doubled the workload for officers on a simple arrest, and more than quadrupled the time needed. The demands from the CPS for, for instance, transcriptions of taped interviews, cost my division, that’s one of 8 in my force, three full time typists. No funding for them of course. Further, the CPS, hit by their own funding problems, demanded that the police supply 8 copies of every damned piece of paper.

Not funded.

By the way, many continental forces are funded differently to the English/Welsh forces and so a lot of the expenditure is hidden. But then you must know that.

The English/Welsh forces have a lot wrong with them but a simple slashing of funding will not give rise to improvement. Walk down the corridor to a management lecturer and ask them, Blair. The police could not cope with the riots of a couple of years ago. What do you think will happen when the next ones arrive? And they will. There’s nothing like too few officers to encourage the lawless.

My division mustered a dozen officers in 1984 for late turn. Since then then division has amalgamated with two other smaller ones. Now four parade on occasion. Four! But the officers can’t say anything as Cameron made it an offence to say how bad the state of policing is in this country. So it is left to ill-informed commentators who have a political axe to grind to confuse the public.

Did you actually ask any officers what their experiences were before you penned this article. Rhetorical by the way.

A very poor article.

This is so woolly on the question of whether the additional spending on the police delivered reductions in crime or not. Yeah, maybe it is difficult to assess. But what we’ve got here is a lot of tangential evidence being used to support the central conclusion – that the money was wasted. That of course would be an exception to the general rule found by other studies (albeit of other periods and places) that increased policing does reduce crime. So the core conclusion is very fragile and, ergo, so are all the later conclusions that follow.