Based on research focusing on England, Prisca Jöst finds that the political behaviour of those on lower incomes appears to be more strongly influenced by their neighbours compared to the wealthy. This finding points to the higher importance of a social norm of voting for the less well-off.

Based on research focusing on England, Prisca Jöst finds that the political behaviour of those on lower incomes appears to be more strongly influenced by their neighbours compared to the wealthy. This finding points to the higher importance of a social norm of voting for the less well-off.

UK citizens on low incomes, similar to those living in other Western democracies, are less likely to vote or engage in other forms of political participation than their high-income counterparts. Despite an increase in turnout rates among low-income voters in the UK in recent years, the participation gap is still big – the 2015 general election, for instance, saw a difference of 22 percentage points in reported participation among low- and high-income individuals.

Considering the UK ranks fifth among the most unequal OECD countries, this pattern of participation is problematic in two key ways. First, it promotes an unequal representation of interests while also undermining the ability of low-income citizens to influence important political decisions. Second, this lack of influence can then lead to increasing social inequality. Income and wealth inequality are already high at the national level, with the top 10% of households having wealth greater than the combined wealth of those on the bottom half. The UK also shows large regional differences, with the southeast ranked as the wealthiest region and the northeast as the most impoverished. To avoid a widening of the already large social gap, it is important to understand under which conditions low-income individuals become politically engaged and how this can potentially be supported through state interventions or non-governmental campaigns.

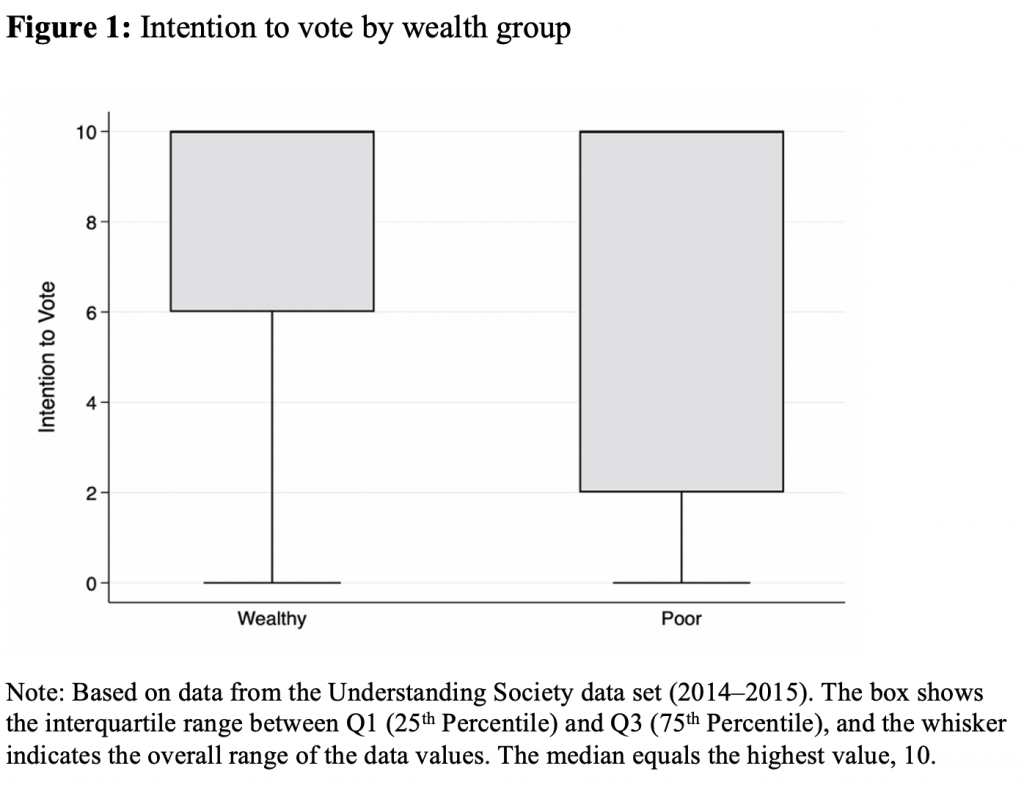

My study of the UK’s 2015 general election finds that intentions to vote were much lower among the less affluent than the wealthy. Yet they also varied considerably among low-income respondents (Figure 1). This implies that future research should no longer simply control for income or wealth. Instead, it needs to investigate, more specifically, the variation among the poor, and among other socially deprived groups.

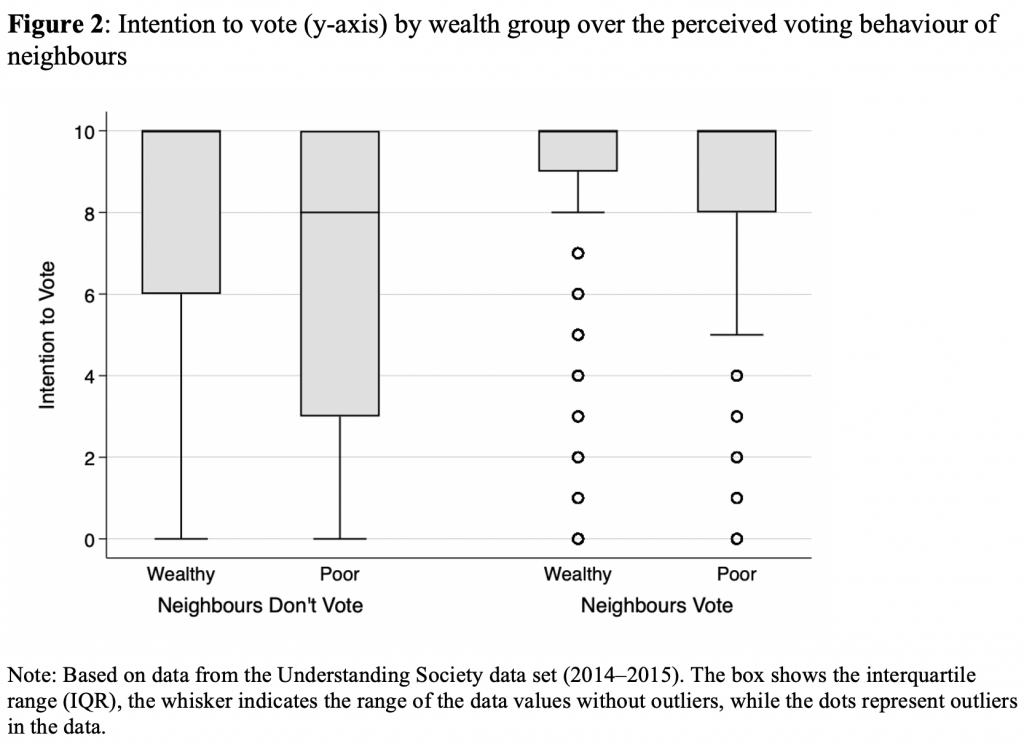

As my research shows, descriptive norms of voting, i.e. whether the individual believes that most neighbours vote, are relatively more important to those who are poorer than those who are wealthy (Figure 2). I also find that when those on low incomes perceive that most of their neighbours vote, their willingness to vote in the next election increases more strongly than the voting intentions of the wealthy. This finding implies that we need to focus more on the social environment and the ties and norms that operate within it to capture what drives individual engagement.

Similarly, compared to residents of wealthier neighbourhoods, those living in more deprived neighbourhoods show higher intentions to vote where they perceive that their neighbours vote. What seems to matter are perceptions of the behaviour of others as they highlight the individual’s social orientation towards those who are expected to behave similarly.

What explains this stronger social influence of neighbours? The sociological literature on neighbourhood effects finds that less well-off individuals are generally more oriented towards others living nearby than wealthy individuals. This partly has to do with the fact that they more frequently rely on their neighbours for help and that they often miss connections to more influential people who they could turn to instead. The less affluent typically also possess fewer connections to individuals living outside the boundaries of their neighbourhood. As a result, social connections to others within the neighbourhood matter more to them than the wealthy.

We may think that low-income citizens are more likely to vote when they think that their neighbours vote either because they have stronger connections to them and feel the need to comply or because they trust their neighbours and want to follow their example. However, the data does not imply that they also trust their neighbours more than the wealthy. This implication suggests that the poor are not generally more trusting than the wealthy but rather that they depend more frequently on their neighbours for help, explain in turn the stronger social ties among neighbours.

The most important finding of this research is that those on lower incomes appear to be more strongly influenced by their neighbours than the wealthy, and this may affect their political behaviour. This finding suggests that strengthening social obligations to comply, such as a social norm of voting, could potentially help to reduce existing inequalities in the political participation between the poor and the wealthy. How socioeconomic background and ethnic or religious identities overlap and how this may change the picture will nevertheless need to be investigated in future work.

___________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Political Studies.

Prisca Jöst is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Gothenburg and will soon join the University of Konstanz.

Prisca Jöst is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Gothenburg and will soon join the University of Konstanz.

Photo by Gleren Meneghin on Unsplash.