Why has British politics been at a seemingly endless deadlock since 2015? Artemis Photiadou brings together the most salient strands of political science research that have attempted to explain electoral preferences, post-Brexit realities, and party politics in 2018.

Why has British politics been at a seemingly endless deadlock since 2015? Artemis Photiadou brings together the most salient strands of political science research that have attempted to explain electoral preferences, post-Brexit realities, and party politics in 2018.

Britain is undergoing a period of contradiction and impasse. As it attempts to ‘take back control’ of its governance and move away from European democratic patterns (though unclear where into) a number of crises have crippled the political system. Political science has tried to make sense of causes and suggest solutions to pressing issues, including the changing nature of the electorate, the persisting fallacies surrounding post-Brexit reality, and the inability of any party to gain the majority’s confidence.

What’s with the electorate?

Much of what we are witnessing as part of Brexit stems from a mismatch between the party system and individuals’ views. We have long known that while parties fall relatively neatly into the left-right axis, voters do not. But recent research by Paula Surridge et al., which asked 30,000 UK voters to place themselves on a range of social and economic issues, has provided much more detail on the multi-dimensionality of voting preferences. Some of the resulting groups fall within traditional left-right politics. But then there were the ‘cross-pressured’ groups: voters who are on the left when it comes to economics (in favour of renationalisation, for example) but are socially conservative (e.g. they are against gender equality). Their opposites also exist. The obvious problem is that no party consistently encompasses such diverse views, so these groups are prone to vote-switching. And thus the unexpected election results we have been witnessing.

The younger section of the electorate also troubled political scientists, particularly whether 2017 saw a ‘youthquake’ in favour of Jeremy Corbyn. The British Election Study team found that turnout increased most in constituencies with more young people, which is not, in itself, evidence that young people voted in larger numbers. But using the much larger sample size of the Understanding Society survey, Patrick Sturgis and Will Jennings found there may have been a small youthquake. More specifically, they found an 8% increase in turnout among those aged 18-24, and a 13% increase in those aged 25-29. Given younger people are more likely to vote Labour, it could be inferred that the party did rely quite a bit on those groups.

Source: Chris Prosser

Source: Chris Prosser

What’s interesting about the two surveys is that their difference comes down mainly to the youthquake age groups. Yet whichever survey’s respondents were closer to giving an accurate picture, neither survey supports claims that there was a 16% increase in the 18-24 group’s turnout, as was initially reported.

Who voted for Brexit?

Besides snap election voters, the question of who wanted Brexit remains. That David Cameron called the referendum without having articulated a coherent narrative as to Britain’s EU membership must not have helped individuals articulate their own views on the matter, especially considering the flood of inconsistent, partisan information they were receiving. Attempting to retrospectively understand support for Brexit, researchers have nonetheless identified a number of key characteristics.

Mobility and location mattered. Katy Morris et al. found that residential immobility was important, with those living in the same region as they were born having been more likely to want to Leave. But this did not hold across the country: immobility mattered only for those in areas experiencing either economic decline or increases in migrant populations.

Age also mattered. Pippa Norris presented evidence confirming how generation gaps divide voters and parties alike, including on Brexit. The Leave campaign mobilized the older generation by harking back to certain nationalistic values, while those born after the 1960s were more pro-EU (and less likely to vote).

National identity mattered also. Anthony Heath and Lindsay Richards found an association between those who identify as English (as opposed to British) and those who prefer a hard Brexit, given that English identity tends to adopt a distinctive, almost ‘nativist’ character on issues such as sovereignty and immigration. The relationship between Englishness and Brexit was echoed by Jan Eichhorn who nonetheless warned that identity is a complex idea and any resulting typologies may end up drawing new dividing lines among the electorate.

While political science often focuses on socioeconomic status and demographics, another factor determining Leave/Remain stances was how we process information. Leor Zmigrod found that those with nationalistic attitudes tend to process information in a more categorical manner, and they do that even with neutral matters that are unrelated to political beliefs. Put simply, the link between cognitive processes and the referendum came down to how flexibly individuals evaluated information.

Further work on perceptions identified a difference between how Leavers and Remainers perceive the economy. Miriam Sorace and Sara B. Hobolt found that Remainers focus on the negative economic consequences of Brexit, while Leavers see the same developments in a more positive light. Similarly, Heather Rolfe found evidence that people tend to rely on personal accounts when it comes to forming views on immigration and to distrust official statistics. So, much of the Leave vote may have been driven by perceptions of immigration and the kinds of views that change often – a big problem when that vote is being treated as sacrosanct by government.

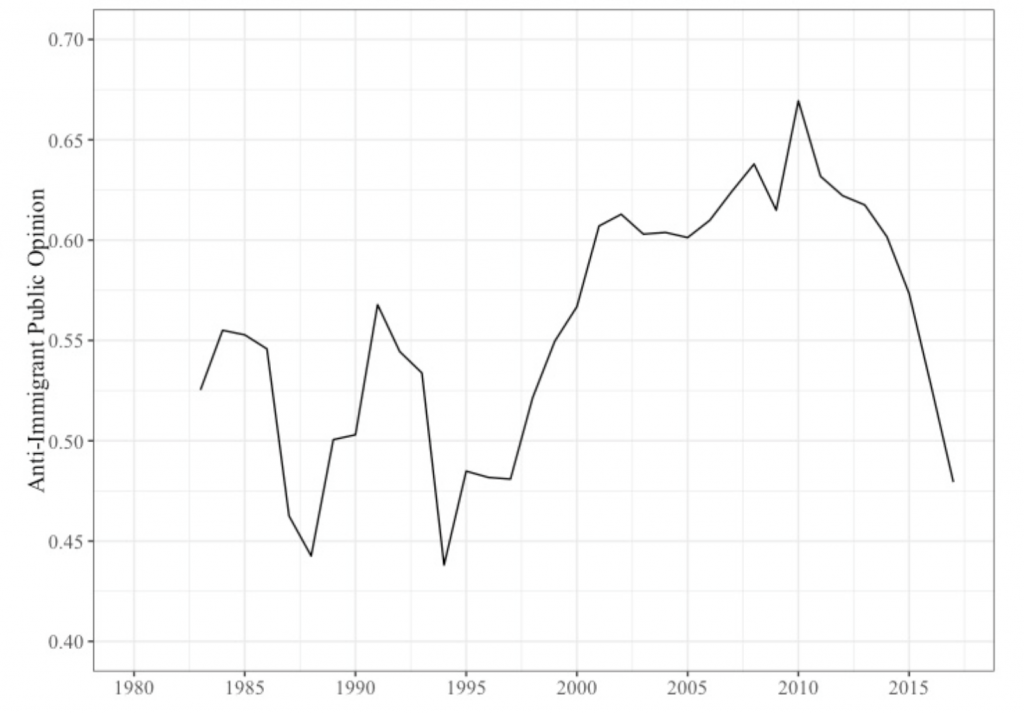

How do we know that perceptions of immigration will change? The concept of the ‘thermostatic’ character of public opinion goes some way in answering this – Britons adjust their views according to government action. Patrick English explained that hostility toward immigration rose in the 1990s and early 2000s as a reaction to New Labour’s multicultural and diversity politics; part of the public thought that this was ‘too much’ and reacted by supporting the BNP and then UKIP. In their turn, the toxic narratives of those parties meant that in the 2010s, the public began to turn the ‘thermostat’ down and oppose anti-immigrant hostility.

Anti-immigrant public opinion in Great Britain (%)

Source: Patrick English

Source: Patrick English

Bursting Brexit bubbles

Other than trying to understand voters, much academic effort in 2018 was spent correcting Brexit fallacies on trade and the economy. Two years in and many people have yet to realise how much they stand to lose from Brexit’s trade restrictions, even if they do not work in the sector. This is no wonder given the government’s promises about unquantifiable economic gains at some point in the future do not explain that in the interim jobs will inevitably be lost. They also do not explain that trade with Europe cannot simply be replaced with non-EU countries. Jeremy Green’s analysis reminded that China is a very different partner to the EU, it has altogether different attitudes on a number of issues, and it is also a rival of the US – Britain’s key ally. Similarly the Commonwealth will not be falling over themselves for deals: the Commonwealth in general does not pursue joint initiatives often, with less than 10% of UK trade exports currently going to those countries. This is not to say that trade with non-European markets is impossible in the long run. But it is much cheaper to trade with neighbouring countries, and will be unavoidable in the short term.

But if prospects are so grim, why does Britain remain a global financial hub? This is because it relies on substantial foreign capital and investment – drawn to the UK due to its single market access – allowing it to delay external deficit reduction, according to Mona Ali. Just how strong and stable Britain’s balance sheet will be when it has left the single market cannot be comprehended before the fact.

Could the Norway model be the answer? Not only would it allow the UK to remain in the single market, but as John Erik Fossum and Hans Petter Graver argued, Norway also indirectly influences the EU’s socio-economic model. Yet they explained that Norway can do that because it has retained a strong welfare state and trust in public institutions is high: neither is the case in Britain. In fact, it is not up to the UK to decide whether it wants the Norway model, and there are good reasons why the EEA may not want the UK joining it – British anti-EU intentions and attitudes may damage trust in, and promote disintegration within, the EEA.

The 2018 party

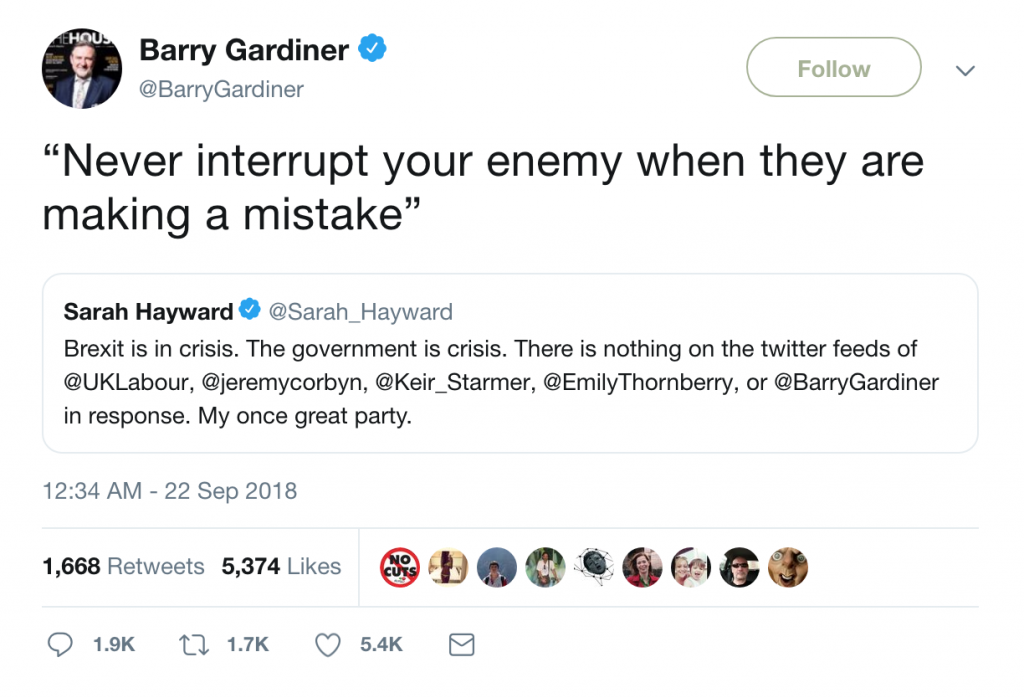

So why is Labour not on top in polls, despite the government’s disastrous performance? Labour has been pursuing a strategy of ‘constructive ambiguity‘, the cause of which was captured on the “Love Corbyn, Hate Brexit” t-shirts worn at its 2018 conference. Labour is an institutionally and ideologically pro-European party, with the membership showing a consistent preference for remaining in the EU. It is Labour’s dear leadership that is at odds with this issue. Unlike the Prime Minister – a Remainer delivering Brexit – Corbyn has always been a Eurosceptic even though he lukewarmly campaigned for Remain. With Brexit not a catastrophe in Corbyn’s eyes, it is not hard to see how Barry Gardiner’s notorious “Never interrupt your enemy when they are making a mistake” tweet from September may explain part of the leadership’s logic. Only when the Conservatives lower the bar enough through their handling of Brexit might Corbyn enter No.10, given how unpopular he is outside Labour. The logic is not only damaging for the country but it is also not working, and Ruth Dixon’s analysis explained that both May and Corbyn are now faring badly even among their own party members.

So why is Labour not on top in polls, despite the government’s disastrous performance? Labour has been pursuing a strategy of ‘constructive ambiguity‘, the cause of which was captured on the “Love Corbyn, Hate Brexit” t-shirts worn at its 2018 conference. Labour is an institutionally and ideologically pro-European party, with the membership showing a consistent preference for remaining in the EU. It is Labour’s dear leadership that is at odds with this issue. Unlike the Prime Minister – a Remainer delivering Brexit – Corbyn has always been a Eurosceptic even though he lukewarmly campaigned for Remain. With Brexit not a catastrophe in Corbyn’s eyes, it is not hard to see how Barry Gardiner’s notorious “Never interrupt your enemy when they are making a mistake” tweet from September may explain part of the leadership’s logic. Only when the Conservatives lower the bar enough through their handling of Brexit might Corbyn enter No.10, given how unpopular he is outside Labour. The logic is not only damaging for the country but it is also not working, and Ruth Dixon’s analysis explained that both May and Corbyn are now faring badly even among their own party members.

Meanwhile, the unambiguously pro-Remain Liberal Democrats have failed to capture Remain voters, not least because of their legacy in coalition. David Cutts and Andrew Russell explained that this is also because elections concern many policy positions and so not all Remainers will abide by an entire LibDem manifesto; exacerbating matters is the fact that since its 2015 wipeout, the party has lost its ability to draw local agendas in order to appeal to various regions.

Who holds the answer?

Dominating the final stages of Brexit is the extent to which the impasse should be broken outside Parliament. Brexit has not been flattering for Westminster’s workings. An example was how little time was allotted to smaller opposition parties for debate, with the SNP having been given just 15′ to scrutinise the devolution clauses of the Withdrawal Bill. Nor has the use of procedures been a highlight of parliamentary democracy, such as when Theresa May decided to call a snap election in order to destroy Labour, not because of a genuine need for one; Labour responded with a ‘bring it on’ attitude and went for a gamble that cost £140 million and elevated the backward DUP to a prime position in UK affairs. So, and while in theory government, opposition, and Parliament could get a backbone in 2019 and stop Brexit on the ground that, however you look at it, such an outcome will be harmful for the common good, in practice some sort of legitimacy will probably be sought from outside.

The prospect of a second referendum has had the consistent backing of a clear majority, as seen in a number of polls this winter. Bruce Ackerman and Sir Julian Le Grand suggested that this time the vote be extended to 16- and 17-year-olds as well as to Britons abroad; crucially, the options ought to be more specific than Leave/Remain. A deliberative forum, such as a citizens assembly, is one way to narrow down the options that make it on the ballot paper – the major difference between such a forum and Parliament is that the former would offer MPs a more detailed understanding of public opinion on Brexit. Jane Suiter has elaborated on how deliberative assemblies facilitated both greater public awareness and better provision of information in Ireland, factors that positively impacted the nature of referendums in that country. These and other aspects that pertain to properly holding a second referendum have been considered in detail by the Constitution Unit.

However the deadlock is overcome, a good proportion of the public will be unhappy with it. But if Brexit does happen, especially a no-deal one, the economic and social inequalities that caused people to want such radical if abstract change in 2016 will only be exacerbated when the negative shock of this decision fully sets in. It may therefore be that 2019 should indeed see the lesser of two evils principle employed, in the form of a properly held second referendum, with the option to remain in the EU.

_______________

Artemis Photiadou is the Managing Editor of LSE British Politics and Policy and a Teaching Assistant in the LSE’s International History Department, where she is completing a PhD.

Artemis Photiadou is the Managing Editor of LSE British Politics and Policy and a Teaching Assistant in the LSE’s International History Department, where she is completing a PhD.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

The show goes on. Although Cameron made it clear the Brexit referendum would be binding, and that Brexit would mean Brexit, i.e, Leaving the EU entirely, and May asserted the same, and her Cabinet, and again during her second tenure as PM, until later in 2018, and Parliament voted it into law, diehard Remainers think to do what Lenin did with the Soviets. And if it doesn’t work out, try something else.

Post-modernism did a job on parliamentary democracy with the connivance, and, the way it looks, by the express collusion, if not direction, of the party apparatchiks, but alongside this development the post-truth era was introduced in political science and the academe generally. It is so obvious, one is tempted to speculate that it is an exercise in political education for the political innocents in the West.

From post-truth we have moved automatically, inexorably, into a state of political simulacrification. This process was tried and tested in international high finance and successfully embedded in national policy making, without much in the way of popular rejection. Economics in the West is also heavily weighted towards simulacrification. Social affairs likewise, due to Facebook, Twitter and so on. Science ditto. Everything is becoming increasingly politicised, hence, simulacrificised. Now the question to be answered in due course, in fact, not some contrived simulacrum, what percentage of the people in the West will take to the simulacra?

We need Euro partners. BUT their running of it has been or appeared to be lazy,, high handed, devoid of debate or information to public, not accountable financially, nor voted for, spendthrift, a gravy train. .

Remain, Reform not leave. .

European democratic patterns or to be more honest severe democratic deficiencies are not something any nation should aspire to.