Cristian Vaccari, Kaat Smets, and Oliver Heath assess public support for the electoral strategies of the main parties in the 2017 election, and examine the extent to which the issues they campaigned on resonated with their own supporters, as well as with the wider public.

Cristian Vaccari, Kaat Smets, and Oliver Heath assess public support for the electoral strategies of the main parties in the 2017 election, and examine the extent to which the issues they campaigned on resonated with their own supporters, as well as with the wider public.

Election campaigns force parties to make difficult choices. Voters’ attention spans, media agendas, and money are too limited to discuss all the issues that party leaders, activists, and voters care about. Hence, parties need to decide which issues to prioritise. Campaigns are often won not by the party making the most compelling argument, but by the party that focuses on the ‘right’ issues that enable it to maximise voter support.

Which issues are the ‘right’ issues has been a matter of debate and contention in the study of voter behaviour. We contribute to this debate in a new article published in West European Politics, where we examine public support for the electoral strategies of the main parties in the 2017 General Election. We assessed the extent to which the issues the parties campaigned on resonated with their own supporters, as well as with the wider public. Did the Conservatives’ overwhelming focus on Brexit alienate some of its own supporters? Was Labour’s decision to fudge Brexit and direct attention elsewhere a successful campaign move?

To answer these questions, we leverage issue yield as a theory of parties’ electoral behaviour. The concept of issue yield takes into account the tension that parties face between trying to appeal to their supporters and attracting new groups of voters. High values on the yield index indicate that the issue in question is both internally popular among party supporters and has broad electoral appeal in the general public. In sum, these are issues on which parties have a distinct competitive advantage.

We test the implications of the issue yield theory based on a unique combination of data representing voters’ preferences and parties’ official campaign communication. For example, based on our data, 77% of the Conservative supporters agreed that Britain should leave the EU, as did a majority of the general population (55%). Moreover, 29% of the population considered the Conservatives as a credible party to achieve this goal. This resulted in a high issue yield because the issue had broad support both in the party base and in the general population, and the party was seen as reasonably credible in implementing the policy.

Based on a survey of an online sample constructed to be representative of the voting-age population, we show that the two main parties had distinctive issue-based competitive advantages. For the Conservatives, the five issues with the highest yield were: protecting the UK from terrorist attacks, leaving the European Union, providing leadership for the country, boosting economic growth, and maintaining Britain’s nuclear weapons. By contrast, for Labour the five issues with the highest yield were: increasing the minimum wage, scrapping or reducing the cost of university tuition fees, improving the NHS, banning zero hours contracts for workers, and protecting pensions.

What issues then did the parties emphasize in their online communication? To understand this, we analysed all tweets posted by parties and their leaders during the 2017 campaign. Looking at the issue each party tweeted the most about reveals the different strategies they employed: leaving the EU for the Conservatives (33.7% of all the tweets they posted), improving the NHS for Labour (18.4%), keeping Britain in the EU for the Liberal-Democrats (25.5%), raising taxes and spending more on public services for the SNP (17.9%), protecting the environment for the Greens (21.4%), and leaving the EU for UKIP (9.2%).

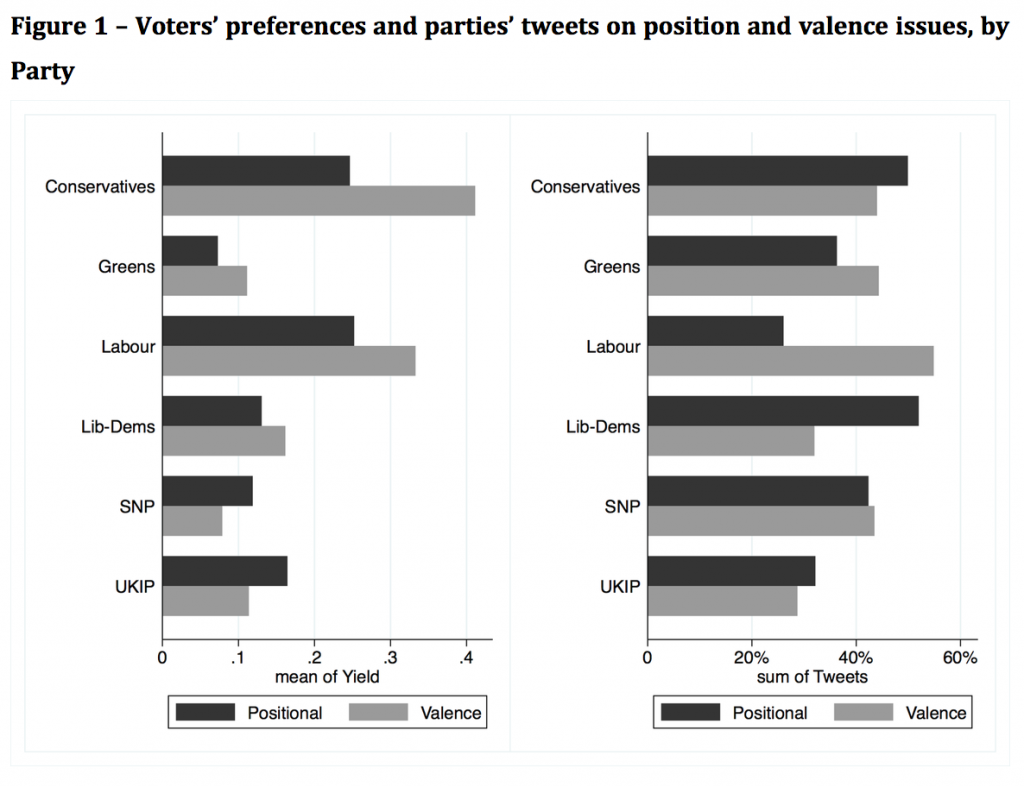

The Labour and Conservative parties employed markedly different strategies in their campaign communications. For one, while Conservatives and Labour posted identical percentages of tweets on taxes and spending (10.7%), the difference could not be starker in terms of Brexit, which was the subject of 33.7% of Conservative tweets and only 0.9% of Labour tweets. Figure 1 compares the preferences of party voters – represented as the average issue yields per party – and the topics of parties’ tweets. The figure uses a classic distinction in political science between positional issues, where parties take clear stances that rule out alternatives (for instance, cutting or raising taxes) and valence issues, which are generally widely agreed upon in the electorate (for instance, reducing unemployment) and on which parties compete in terms of how competent they are in achieving those goals.

From the right panel of Figure 1 we can see that the Conservatives focused on positional issues (by and large Brexit) more than any other party (apart from the Lib-Dems, who emphasised the opposite position on the same issue) and nearly twice as much as Labour. By contrast, Labour mostly focused on valence issues. Four of the top five issues in the party’s and its leader’s tweets addressed uncontested policies (improving the NHS, protecting pensions, improving the quality of schools, and fighting crime). Most of Labour’s messaging was aimed at reminding voters the party was committed to those widely agreed societal goals rather than taking more controversial stances on the means by which this purpose would be achieved.

Another important difference between the two main parties’ communication is that the Conservatives were noticeably more focused (and repetitive) than Labour. The Conservatives’ laser-like emphasis on leaving the EU, providing leadership for the country, and boosting economic growth meant, however, they did not capitalise on other issues where they also enjoyed large competitive advantages. For example, the Tories had the largest issue yield with respect to protecting the country from terrorist attacks, but only 4.6% of the tweets they posted during the campaign focused on this topic. Mrs May’s party also stood to benefit from talking about maintaining the UK’s nuclear weapons and fighting crime, but Conservatives only talked about those issues in 2.6% and 2.1% of their tweets.

The results from our analysis indicate that the Conservative campaign did not fully exploit the opportunities for expanding support that were open to them had they presented a broader agenda than the one they ultimately ran on. Our analysis indicates the Tories went overboard in their rhetoric on ‘getting on with the job’ of Brexit (which risked alienating their more moderate supporters who were uneasy about it) and ‘strong and stable leadership’ (which, repeated relentlessly during the campaign, ended up opening the door for mockery of May’s rigid communication style).

By contrast, Labour played a better hand and tapped into most of its electoral strengths. There is a clear left-wing anti-austerity constituency in Britain, and rather than being out of touch with the public mood, as many New Labour grandees feared, our analysis shows that Labour’s message under Corbyn resonated both with party supporters and the wider public. By offering its supporters policies they strongly agreed with, Labour also thwarted the electoral threat potentially inherent in its vague position on Brexit.

As the country gears up for another election it remains to be seen what lessons, if any, the two main parties have learned from the last campaign. While it seems clear that Boris Johnson is keen to broaden the debate beyond Brexit, emphasising law and order, education, and the NHS in recent weeks, it remains uncertain whether avoiding Brexit in favour of other policies will serve Labour as well next time as it did previously.

__________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in West European Politics.

Cristian Vaccari is Professor of Political Communication and Co-Director of the Centre for Research in Communication and Culture at Loughborough University. He studies political communication by elites and citizens in comparative perspective using a variety of methods. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of Press/Politics and the author of Digital Politics in Western Democracies: A Comparative Study (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013). He tweets as @prof_vaccari.

Cristian Vaccari is Professor of Political Communication and Co-Director of the Centre for Research in Communication and Culture at Loughborough University. He studies political communication by elites and citizens in comparative perspective using a variety of methods. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of Press/Politics and the author of Digital Politics in Western Democracies: A Comparative Study (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013). He tweets as @prof_vaccari.

Kaat Smets is Senior Lecturer in Politics (Quantitative Methods) in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her research interests include political behaviour, political attitudes, elections, political sociology, comparative politics and research methods. Kaat is co-editor-in-chief of Electoral Studies.

Kaat Smets is Senior Lecturer in Politics (Quantitative Methods) in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her research interests include political behaviour, political attitudes, elections, political sociology, comparative politics and research methods. Kaat is co-editor-in-chief of Electoral Studies.

Oliver Heath is Professor of Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London and co-director of the Democracy and Elections Centre. He tweets as @olhe.

Oliver Heath is Professor of Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London and co-director of the Democracy and Elections Centre. He tweets as @olhe.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).