Charlie Young explores how we can test a universal basic income in the UK and beyond. Drawing on research for the RSA, he maps a version of this idea that brings together a heterogeneous field of proposals, and explains that the quality of experimental design impacts on how well the policy is understood and whether it is supported by the public.

Charlie Young explores how we can test a universal basic income in the UK and beyond. Drawing on research for the RSA, he maps a version of this idea that brings together a heterogeneous field of proposals, and explains that the quality of experimental design impacts on how well the policy is understood and whether it is supported by the public.

Basic income, only a few years ago a fringe idea, is rapidly breaking through into mainstream political discourse. The policy has entered into the popular imagination amidst widespread disenchantment with a dysfunctional status quo, as a new UK-wide survey commissioned by the RSA has found. 45% of those surveyed believe that basic income would do a better job providing security than the status quo, compared to only 13% who disagreed, while more than twice the number of people support basic income than oppose it. It’s worth noting that there are always limits with this type of exercise and people were only responding to the idea in principle, but these are important findings and are particularly helpful in terms of gauging levels of public engagement – which are clearly high.

Internationally we can see a similar interest, evidenced by the proliferation of basic income experiments and pilots around the world in recent years. Canada, Finland, Kenya, The Netherlands, Uganda and others are currently running trial schemes, with governments and local authorities eyeing up potential projects in the UK, Barcelona, India and the United States. Similar discussions are underway in France, Portugal, Italy, Serbia, South Korea and elsewhere. Things seem to be moving quickly. This is an idea that needs to be taken seriously.

Back on UK soil, our survey also found that 40% of respondents would welcome experiments in their local area, compared to only 15% that would oppose such a development. This would suggest general support for the Scottish experiments currently under consideration, and that the public may well be broadly behind John McDonnell’s recent announcement that basic income experiments could be in Labour’s next manifesto.

However, if we’re going to move ahead we have to disentangle the different kinds of basic income so we know what we’re getting ourselves into and take people’s concerns and opinions into account. Many seem to think that basic income is a single, homogeneous concept, but it’s fundamental that we treat it as the heterogeneous field of proposals that it is. There are a wide variety of applications of the idea some of which are compatible, some of which conflict.

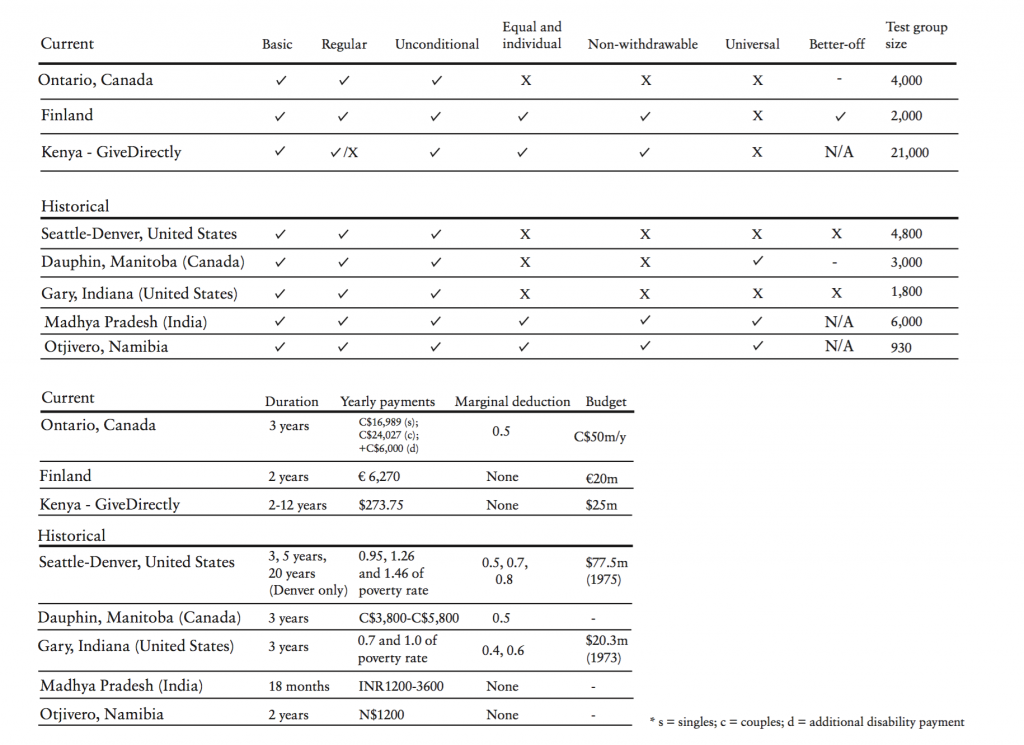

Our report, Realising Basic Income seeks to clarify these complexities and distinguish between the many different ‘styles’ of basic income. We’ve done this by setting different iterations of the policy against a comprehensive set of widely accepted basic income principles. These include things like universality, unconditionality, regularity and non-withdrawability (payments not being reduced as earnings rise); ideas that are relevant to what we refer to as the ‘ideal type’ basic income. Even though they all call themselves and are referred to as ‘basic income’, very few experiments, historical or contemporary, fulfil all of the principal criteria – certainly none in the western world. The table below should give an idea of the diverse range of experiments implemented so far.

Historical and contemporary basic income-type pilots and experiments against core basic income principles

It’s important to clarify that even though these don’t match up to the ‘ideal type’, we’d argue that there’s little use in being purists about this. Each application of the idea has something to teach us, and it’s just important that we understand their differences (and what their implications might be).

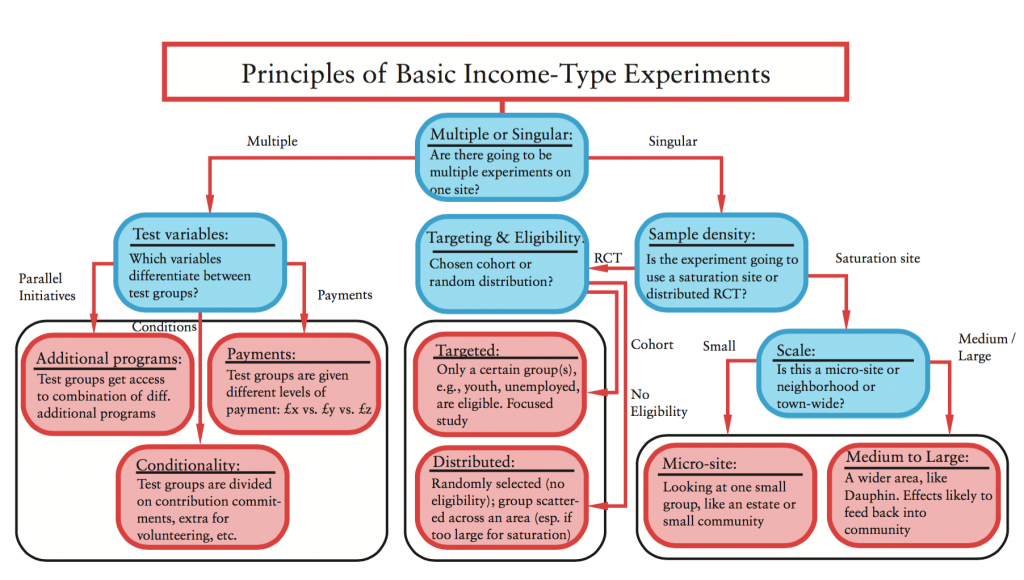

This variety of expressions of basic income is mirrored by a collection of different experiment architectures: from saturation sites, where every member of the community has the option to receive basic income payments, to experiments with randomly distributed and selected participants; from simplified flat payments that aren’t withdrawn as earnings rise, to staggered payments for different subgroups, each of which have distinct effective marginal tax rates (which have historically reached 80%). Others are universal programs, whereas most focus solely on those of certain income or employment status (hardly ‘universal’). Some experiments see payments made to individuals while for many, payments are made on a household basis.All of these factors have significant implications for the policy’s character.

There are also big differences in duration: most of the experiments have run or are running for around 2 years, others for over a decade. We’ve categorized and systematized the core characteristics of these experiments and developed a basic income experiment typology (which hadn’t been done previously) incorporating major and minor variables: like whether to have one or multiple concurrent interventions, for the former; or whether to give out part of the basic income in a local or crypto-currency, for the latter. The major variables are laid out below and should give an idea of the different avenues for basic income experiment design and implementation.

Decision-tree detailing key categories of basic income- type experiments

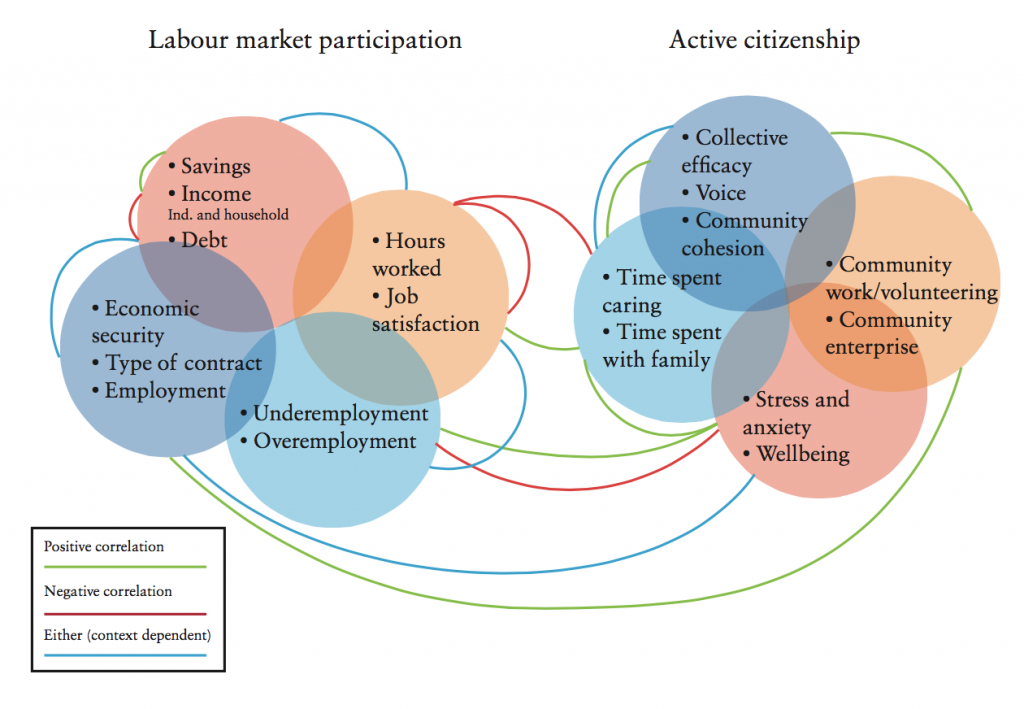

The principles checklists and experiment architectures are also intimately related to assessment and evaluation, a critical feature even at the design stage. We saw a gap in basic income impact assessments, with most experiments focusing solely on employment, poverty or some other single headline indicator. This gap should be filled with a more dynamic model. Fully understanding the impacts of basic income requires research into secondary and tertiary impacts – social and multiplier effects. For example, experiments should be looking at the effect of payments on economic security, the knock-on effects on wellbeing and how changes affect time spent with family or in the community. Basic income is a systemic intervention and should be treated as such. With the aid of new technologies and historical insight, we’ve outlined the primary features of a methodological approach that might be able to rise to such a challenge.

An example visualisation of dynamic relationships between two first-order impacts and their sub-variables

To aid in the practical application of the idea we’ve also looked at likely interactions between basic income and the UK tax-benefit system, as well as the role of the DWP and HMRC, and some of the policy mechanisms through which experiments could be implemented. There are also a detailed outlines of four different scenarios for basic income experiments, each costed and explained in logistical and policy terms – demonstrations of both feasibility and the variety of creative and imaginative ways to enact basic income policy.

To aid in the practical application of the idea we’ve also looked at likely interactions between basic income and the UK tax-benefit system, as well as the role of the DWP and HMRC, and some of the policy mechanisms through which experiments could be implemented. There are also a detailed outlines of four different scenarios for basic income experiments, each costed and explained in logistical and policy terms – demonstrations of both feasibility and the variety of creative and imaginative ways to enact basic income policy.

Realising Basic Income is intended as a toolkit to be used by any and all interested in making basic income experiments a reality, both in the UK and further afield. It is an effort to amalgamate experiences from across the globe over recent decades in academia, advocacy, on-the-ground experimentation, policy formation, and associated research and analysis.

Now that basic income is advancing toward real-world application we believe it’s urgent that we clear up the confusion around basic income and understand the policy (or field of policies) in a clear and comprehensive way. This is what we’ve set out to do, and it’s a crucial approach for advocates looking to communicate and collaborate across borders, ideologies and disciplines for a richer and more coordinated approach to realising basic income worldwide.

________

Note: the full report on which the above draws is available here.

Charlie Young is a Research Associate at the RSA specialising in basic income, and has a background in economics, anthropology and climate change. His work focuses on new economics and analysing the socioeconomic impacts of policy interventions.

Charlie Young is a Research Associate at the RSA specialising in basic income, and has a background in economics, anthropology and climate change. His work focuses on new economics and analysing the socioeconomic impacts of policy interventions.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.