Inheritance tax systems can play an important role in increasing social equality, yet across the world, these systems often struggle to achieve their intended aims. Étienne Fize, Nicolas Grimprel and Camille Landais outline four key ways in which they can be improved and reformed for modern conditions.

There is a strong case to be made that inheritance taxation is desirable both from an economic and normative standpoint, as we argue in a recent study. We are in a unique historical period where restoring progressivity in the taxation of inheritance flows appears critical to prevent the extreme concentration of wealth at the top, the solidification of a dynastic class of rentiers, and the demise of social mobility along the wealth distribution.

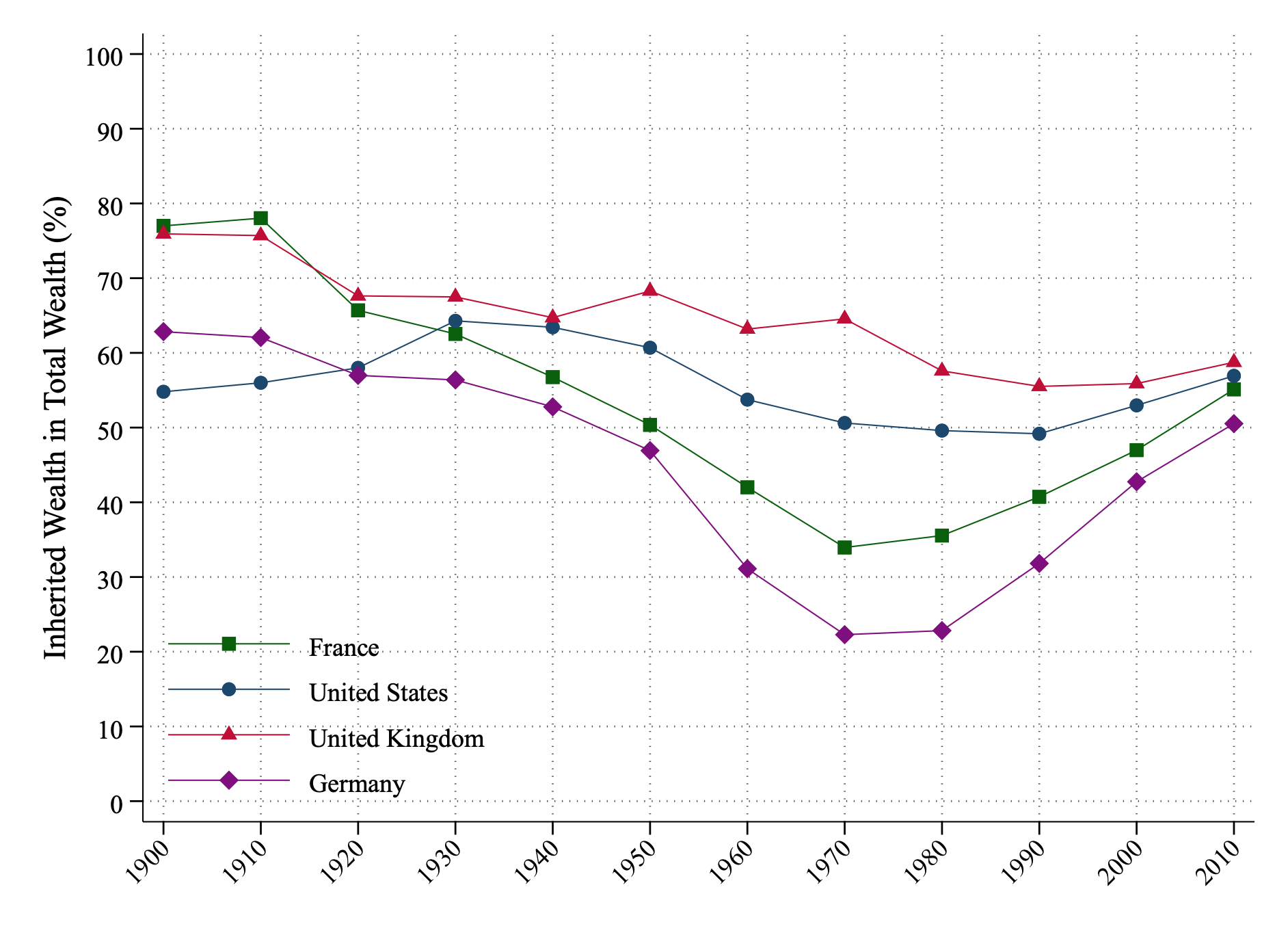

Yet, faced with such urgency, the inheritance tax systems of most western economies are failing on all fronts. They are achieving less and less in bringing about a more equitable society in major liberal democracies, and yet incurring substantial unpopularity at the same time. One indicator of their increasing lack of traction is shown in Figure 1, where it is apparent that the once-substantial equalising impact of inheritance taxation in Germany, France and even the United States circa 1970 has long ago dissipated – while in the UK the tax’s impact was always rather slight.

Figure 1: The evolution of inherited wealth as a share of total wealth

Note: Simplified definitions using inheritance vs. saving flows; approximate lower-bound estimates. Source: Alvaredo, Garbinti and Piketty (2017)

It is clear that inheritance taxes have failed in hindering the return of inheritance as the main driver of individuals’ wealth rank in society. In addition, they have failed at being truly progressive, with people in the top of the inherited wealth distribution benefiting from various unjustified tax loopholes.

Finally, they have failed to be accepted and truly understood by the public, both in terms of their aim and functioning. Most inheritance tax systems are therefore broken and unable to cope with the task. Unless they can be greatly improved and reformed, there is a very real risk that more countries will engage, like New Zealand (in 1992), Sweden (in 2004), or Austria (in 2008), in abolishing estate or inheritance taxation altogether.

We propose four general principles that would make inheritance taxation more efficient and transparent, while restoring its intended progressive effects: switching to a system based on total lifetime inheritance flow, instead of taxing each transmission independently; eliminating most tax loopholes, especially those that do not bear economic justification, and reinforcing the effective progressivity of the inheritance tax schedule; redistributing generated tax revenues as a wealth endowment for all to alleviate inefficiencies generated by credit constraints and allowing for productive investments at the bottom of the wealth distribution; and creating an efficient and transparent information system to assess and adjust the inheritance tax system over time.

Taxing lifetime inheritance flows

Inequalities in the wealth inherited by individuals over their lifetime are extreme. They are also much stronger than the inequalities that one may observe from annual inheritance transfers in isolation. This is due to the richest heirs tending to receive numerous transmissions of similar value throughout their lifetime.

These transmissions generally come from several family members, and are split into both donations and inheritance. The current inheritance tax systems of most western economies, because they tax each transmission independently, allow the richest families to optimise the timing of transmissions and benefit several times from the tax exemption threshold in place.

The independent treatment of each transmission plays an important role in explaining the gap between the very progressive tax scale displayed, and the much lower effective tax rates incurred by individuals at the top of the wealth distribution. It also unfairly penalises individuals that receive fewer or more uneven transmissions, and therefore feeds into the unpopularity of inheritance taxes among the public.

Switching to a system based on total lifetime inherited wealth, rather than individual transmissions, would prevent such timing optimisation on the part of the richest families, while making it fairer to people receiving fewer and/or more uneven transmissions. It would also permit a less aggressive tax scale, with a higher exemption threshold, and make the system more transparent to the public by reducing the gap between the tax scale displayed and the tax rates effectively incurred.

In addition, a system based on lifetime inheritance would eliminate the distinction between direct and indirect transmissions, and also distortions in the timing of transmissions. Several countries, such as Ireland, have already successfully switched to a lifetime-based system. Building on these first experiences, we also know that the move to a lifetime-based system does not require heavy technical adjustments, conditional on being able to record individuals’ total inherited wealth over time.

Eliminating tax loopholes

In the United States, inherited estate wealth of more than a million dollars faces a marginal tax rate of 40%. In France, the marginal tax rate for direct transmissions above €900,000 is 40%, and 45% for wealth exceeding €1.8 million. Yet, the effective tax rate incurred by individuals at the top 0.1% of the inherited wealth distribution hardly reaches 10% in France, despite these individuals inheriting on average €13 million over the course of their lives.

There is no strong economic argument for taxing life-insurance at a lower rate relative to other types of transmitted wealth. Life-insurance should be integrated into the general inheritance tax regime. Similarly for trusts, the tax exemptions and/or rebates in place do not provide any credible efficiency gain, while almost exclusively benefiting the top of the inherited wealth distribution. Taxing transmissions through trusts should be done in the same way as any other type of transmitted wealth.

Using inheritance tax revenues to fund wealth endowments for all

Guaranteeing a wealth endowment for all is desirable for both equity and efficiency reasons. Providing a wealth endowment to individuals with no or very little wealth would reduce the severe inequalities observed at the bottom of the wealth distribution.

Such a wealth transfer would also alleviate inefficient credit and liquidity constraints that prevent productive investments in education, businesses, or housing. The benefits of this reform explain why it has frequently been put forward by economists. Such a system could be based on citizenship at birth, and the wealth transfer to all citizens could be made when individuals reach the age of 18 or 25, or at the time of the first received transmission.

To really alleviate liquidity and/or credit constraints, the wealth transfer also has to be large enough. Previous research shows that small transfers of wealth do not allow poor individuals to sustainably invest and to consequently escape poverty. This poverty trap motivates our argument for a large, one-off wealth transfer, rather than for monthly or yearly benefits.

The transfer should also not be conditioned or constrained in its use. Paternalistic concerns that the acquired wealth would be ‘misused’ or affect individuals’ labour supply are not supported by the empirical literature. And of course, such concerns are rarely raised when it comes to wealth transfers at the other end of the wealth distribution.

Building efficient and transparent information systems

The three suggestions above can all be implemented independently from one another. Yet all of them require an efficient and transparent information system. A lifetime-based inheritance tax system must be able to track individuals’ accumulated inherited wealth over time.

Reducing the scope of tax loopholes and preventing abuses implies that the tax authorities will have sufficiently precise data on individuals’ inherited wealth in order to effectively conduct monitoring and inspections. Redistributing the tax revenue as wealth transfers requires being able to effectively estimate the revenue generated by inheritance tax.

Moreover, these transfers can only be targeted to the bottom of the wealth distribution if individuals’ full wealth is being precisely recorded. Finally, an efficient and transparent information system is necessary to be able to predict and evaluate the effects of the reforms, and to adjust the system as required.

The above draws on the authors’ study in LSE Public Policy Review’s November 2022 issue on Tax Justice.

This blog post appeared originally on our sister site LSE Europp.

Étienne Fize is an economist at the French Council of Economic Advisors (CAE). He obtained his PhD from Sciences Po Paris in 2019.

Étienne Fize is an economist at the French Council of Economic Advisors (CAE). He obtained his PhD from Sciences Po Paris in 2019.

Nicolas Grimprel studied at PSE – Ecole d’économie de Paris – the Paris School of Economics and is a Pre-Doctoral Research Fellow in Public Economics (STICERD) at LSE.

Nicolas Grimprel studied at PSE – Ecole d’économie de Paris – the Paris School of Economics and is a Pre-Doctoral Research Fellow in Public Economics (STICERD) at LSE.

Camille Landais is a Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics and Director at Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD). He is also Co-Editor of the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Camille Landais is a Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics and Director at Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD). He is also Co-Editor of the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Photo by Sasun Bughdaryan on Unsplash