Religion and racism are topics often discussed together. Newspapers regularly make headlines based on misrepresented data, most recently regarding British Muslims – a religious group that is often the target of both blatant racism and of more subtle forms of racial profiling. But Stefanie Doebler explains that rigorous use of surveys shows that religion does not facilitate racist attitudes; poverty and low education are some of the factors that do.

Religion and racism are topics often discussed together. Newspapers regularly make headlines based on misrepresented data, most recently regarding British Muslims – a religious group that is often the target of both blatant racism and of more subtle forms of racial profiling. But Stefanie Doebler explains that rigorous use of surveys shows that religion does not facilitate racist attitudes; poverty and low education are some of the factors that do.

In the current climate of fear of terror, religion and racism are hot topics. Muslims are often not only a target of racism, but also find themselves misrepresented as being intolerant in media stories. The misuse of survey data by the press only makes people increasingly doubtful as to their value. But used responsibly, surveys can give valuable insights that can help us understand why some people are more likely to endorse racist attitudes than others.

My research on religion and racism in Europe highlights three key findings: firstly, racist attitudes are to a large extent explained by low education, socio-economic deprivation, older age and insecurity, but not religion. Once these variables are taken into account, religious identities and devoutness matter only little. If anything, belief in God, no matter whether it is a personal God or a Spirit/Life Force is significantly negatively correlated with racism. The findings are based on the European Values Survey 2008 and are robust across 47 countries.

The most recent data available for Britain, the 2013 British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, confirms this picture. It contains a question measuring social distance, “Would you mind if one of your close relatives were to marry a [Muslim/Asian/Black] person?”. Each question has three answer categories (a lot, a little, would not mind; for ease of comparison, ‘a lot’ and ‘a little’ were collapsed into one category). The BSA also asks about religious identities and church attendance. Of the 3,244 individuals who took part, a sub-sample of 1,958 was asked the question on marrying a Muslim, and another sub-sample of 946 was asked this question referring to Asians and Black people.

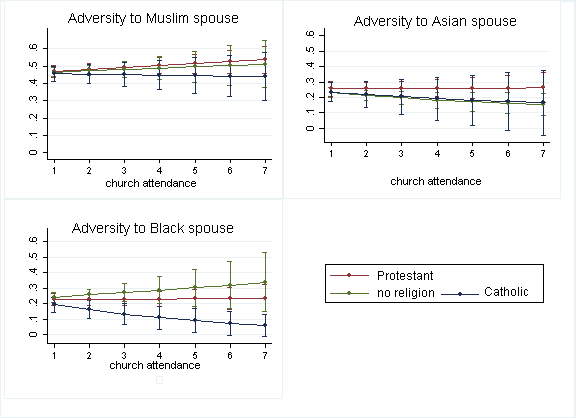

Figure 1 summarizes the main findings (based on three separate binary logistic regression analyses). The models include religious identification (Protestant, Catholic, other and non-religious) and church attendance and take into account the effect of education, low-income, sex, age, and unemployment.

Figure 1: Adversity to Muslim and Minority Ethnic Spouse

The graph shows the likelihood of white majority Catholics and Protestants resisting intermarriage with Muslims, Asians or Black people, by church attendance (a score of 1 would mean absolutely certain to say “A lot/a little”, a score of 0 would mean certainty to say “would not mind”). Across the groups, white majority members are almost twice as likely to reject Muslims, than Asians and Blacks, as relatives by marriage. The only relationship for which church attendance does make a noticeable difference is Catholics being more tolerant toward intermarriage with Blacks than the non-religious (albeit the difference matters only for the very devout).

One caveat of the BSA is that its numbers of Muslim respondents are too small for comparisons. However, the Ethnic Minority British Electoral Study (EMBES) is a rare random sample of 2,787 minority ethnic citizens and allows for comparisons between minority Muslims, Christians and other religions (Jewish, Hindu, Sikh). Because religion and ethnicity overlap, ethnicity was collapsed into crude categories: Black (N=884), Asian (N=1,826), Mixed (N=75). The EMBES has a social distance measure that is very similar to the ones used in the BSA, adversity towards having a white person marry into the family. Only 14 per cent of the minority ethnic sample said they would mind having a white person marry into the family, while 51 per cent did not mind at all. But while only eight per cent of non-Muslims said they minded “a great deal”, the number was considerably higher among Muslims, 13 per cent.

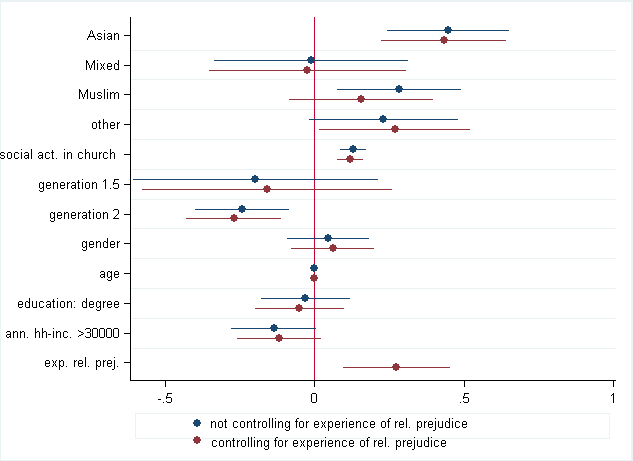

Figure 2 shows the effect that certain characteristics have upon this attitude. Dots to the right of the vertical red line boost intolerance, dots to the left reduce it. If the line emanating from the dot crosses the horizontal red line, the characteristic does not have a significant effect. Two models were run. The first model – the blue dots – does not include whether the respondents had experienced religious prejudice from the white majority. The red dots represent a second model including this experience. When we take into account experiences of white majority prejudice, being a Muslim no longer makes a difference.

Figure 2: EMBES – Adversity to intermarriage with white majority

In other words, British Muslims express strong social distance to whites only when they think that the white majority is prejudiced towards them. Otherwise, they are no more racially intolerant than Christians, Sikh, Jewish, or the non-religious. This is my second key finding.

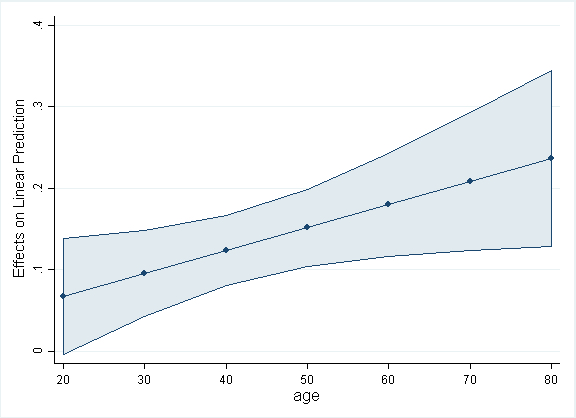

Being socially engaged in a church or mosque does appear to be significantly related to higher racial intolerance, but Figure 3 demonstrates that this is mostly due to older minority generations being more intolerant than younger ones.

Figure 3: The effect of attendance at religious services by age on likelihood of intolerance

Figure 3 shows that for older respondents, the effect of going to church increases predicted levels of racism. For the youngest age group, the result is insignificant (the area surrounding the markers, the 95 per cent confidence interval, crosses zero). Other research e.g. by Rob Ford found the same age-related pattern for the white majority.

My third key finding is that when it comes to national contexts, racist attitudes are largely explained by poverty (low GDP), low political stability, and legacies of conflict. Countries where these factors are prevalent are the only part of Europe where religion is consistently related to racism, often intertwined with nationalism. Examples are post-conflict societies such as Kosovo, Armenia, Northern Ireland and countries of the post-communist East that have undergone major system transitions. Populations of the wealthy, politically stable West are consistently more tolerant on average.

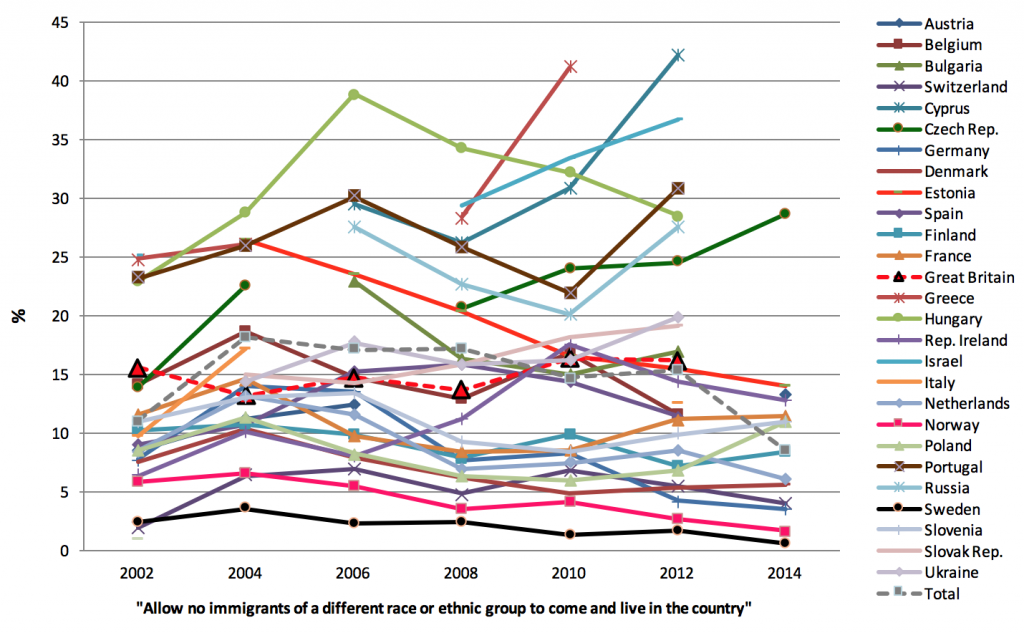

Figure 4 is a line chart of the percentage in each country who agrees to the statement “no immigrant of a different race or ethnicity should be allowed to come and live in the country”. The European Social Survey (2002-2014) is the most recent time-series available. Britain is shown as the bright red, dotted line at the centre.

Figure 4: % who agree to the statement “no immigrant of a different race or ethnicity should be allowed to come and live in the country” by country

The pattern for Britain and Western Europe is stable over time. Average rates of racial intolerance vary between two and 15 per cent, with a weak tendency toward decrease in some countries. Eastern Europe is the exception: While Bulgaria, Estonia, and Hungary, for example, exhibit steep decreases in racism between 2006 and 2014, others, such as the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Russia show dramatic increases in racism between 2008 and 2010. This could be a response to the economic shock of the 2009 recession.

It is too early to tell whether the refugee crisis will lead to a wave of racism across Europe. What is more certain is that neither sensationalist media misusing data, nor ill-advised counter-radicalization policies that single out entire religious sub-populations, are helpful in combating intolerance and creating the mutual trust that modern societies need to live in harmony.

___

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Politics and Religion.

Stefanie Doebler is Research Fellow in the School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology at Queen’s University Belfast. She tweets from @stefdoebler

Stefanie Doebler is Research Fellow in the School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology at Queen’s University Belfast. She tweets from @stefdoebler

Why is the Orthodox Church not in the graphs but you mention Orthodox Countries

Hello there

I was wondering how you plot non religious people on a church attendance scale and expect to get reasonable data? I know no one who is both atheistic and goes to a church on a regular basis. (Other than to go in to look at the art). Is the regression based entirely on points at the low attendance side of the scale? I see that the confidence intervals expand rather a lot for the non religious group as opposed to the religious groups. Would you mind sharing the data?

Best regards

Andrew

No mention of the Papal Visit of 2010 and the preceding Polish Catholic immigration.

Or of the constant attacks on Catholic schools in this country.

I wonder why?