Andrew Glencross examines some of the key policy challenges that arise from the UK’s need to renew and rethink bilateral relations with a number of European countries after Brexit.

Andrew Glencross examines some of the key policy challenges that arise from the UK’s need to renew and rethink bilateral relations with a number of European countries after Brexit.

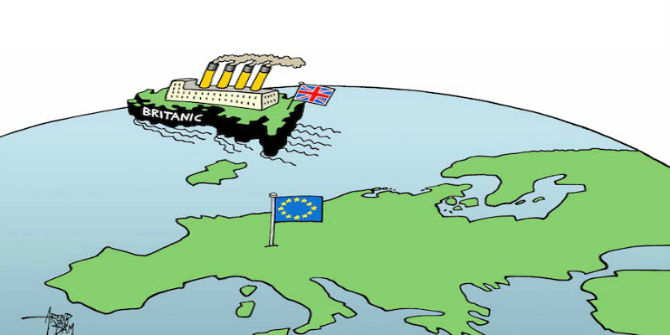

The 2016 referendum fundamentally unsettled the UK’s diplomatic moorings. Up to this point, the UK had treated EU relations as a subset of its broader multilateral strategy for promoting its interests. Outside the EU club, the UK now faces having to engage with Brussels via a bilateral strategy of nurturing relationships with key member states and their leaders. But relying on bilateral ties to influence the EU is a highly demanding proposition, as a recent policy report demonstrates.

Bilateral engagement is a fickle thing, because it is often based on personal relations between leaders that can be upended by shifting political currents at home or abroad. So what can be learned by scrutinizing the variety of cross-cutting economic, security, and diplomatic concerns that characterize British engagement with individual European countries after Brexit? Three lessons emerge from our analysis of UK relations with France, Spain, Turkey, and the Visegrad Four (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia).

The demand for renewing ties with the UK

The good news is that – despite Brexit – there is genuine appetite for renewing bilateral ties with the UK across European capitals. France, Spain, Turkey, and the Visegrad Four (V4) all consider London a partner of special importance, although the level of institutionalized cooperation differs between them. In the wake of the Brexit vote, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office recognized the need to bolster resources in the EU-27, reversing recent policy of privileging Asia over Europe. In Spain, for instance, a senior diplomat was appointed to a newly created role as Counsellor responsible for bilateral relations and the regions.

Diplomatic investment also needs to be backed by committing political capital. To that effect, it is no surprise that several high ranking cabinet members have visited each of the V4 countries since 2016; as Prime Minister, Theresa May twice went to Poland and once to Slovakia. Perhaps the most tangible outcome of these efforts – aimed in large part at garnering support for the UK’s Brexit negotiating policy – however was the treaty on defence and security cooperation which the UK signed with Poland in December 2017. Similarly, the UK and France sought to extend the remit of their security partnership in the aftermath of the 2016 referendum. Theresa May and Emmanuel Macron clearly had rather diverging views on the benefits of leaving the EU and on what terms this should happen, but this did not stop them from proceeding with a range of joint initiatives announced at the Sandhurst summit in 2018. The UK’s statecraft has also been evident in the way it has handled the AP government in Ankara. In what is a particularly strained moment in Turkish-US and wider Turkish-NATO relations, the UK is one of the few countries that has managed to increase military cooperation with Turkey.

The risks of relying on bilateralism

There is, however, another side to the positive story of re-engaging with European capitals after the Brexit referendum. It is an inherently risky move in a twofold sense. It requires the cultivation of goodwill, which might put the UK in a bind including in reputational terms, and risks creating the false hope that bilateralism can compensate fully for the lost benefits of EU membership.

Promoting goodwill in Spain, Turkey or the V4 is not a cost-free enterprise, especially as the power asymmetry has tilted in their favour. The turning of tables is clear in the Brexit negotiations, where Spain expects to see flexibility in the UK’s stance on Gibraltar, and the V4 have expressed concern that their ex-patriates living in the UK have their rights protected. Moreover there is potential for reputational damage by over-investing in what are, from an EU perspective, awkward partners such as Erdogan in Turkey or Orban in Hungary. These authoritarian leaders are grateful for any additional legitimization that they can derive from high-level UK engagement.

There are two reasons why heightened UK expectations of relying on enhanced bilateralism to maintain a significant role regionally and on the global stage could set the stage for new disappointment. Firstly, the UK needs to be able to give a clear message to its partners about where and how it is willing to cooperate. EU withdrawal militates against this by taking up government bandwidth and creating unprecedented political and policy instability. Secondly, no single country has the sway to create and sustain joint EU-UK enterprises, while the EU has gained an unprecedented ability to exclude the UK – as it did with the military element of the Galileo satellite navigation system in 2018. Expecting France, with which the UK has the most institutionalized security relationship, to bring the EU onboard is hardly foolproof.

One UK diplomacy or several?

Finally, it is important to remember that the UK is a multi-national state with a complex system of devolved governance. These devolution arrangements are in flux because of Brexit and can potentially impact the coherence of UK diplomacy. The Scottish Government, Welsh Government and Northern Ireland Executive will have to rethink their own EU engagement strategies. Their access to governmental lines of communication will be cut off as they transition from internal decision-makers with a seat around the table at EU Council meetings on devolved matters, to external observers.

The EU footprint of Britain’s nations and regions will thus have to be recalibrated as Brexit enhances the incentive for Britain’s devolved authorities to foster their own relations in Europe via regional representative offices. This in turn is bound to create new coordination challenges within UK diplomacy, notably in the contentious area of EU-UK trade where every part of the UK has its own vested interests. To overcome the resulting domestic tensions, the UK – if it stays intact as a sovereign state – will need to set out common negotiating frameworks to preserve the UK’s single market as advocated by the Scottish Parliament.

Not losing friends

Given the torturous nature of the Brexit negotiations, one could be forgiven for thinking that the government’s strategy in Europe of late has been an exercise in how to lose friends and alienate people. But the reality is far more complex as the demand for renewed bilateral engagement is real and yet counterbalanced by the new risks this approach entails. Charting this new course will prove extremely taxing as it also involves rethinking European engagement from the perspective of the UK as a multinational state.

________________

Andrew Glencross is Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Aston University.

Andrew Glencross is Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Aston University.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Bilateralism? I think UK relation will be with the EU rather than each country.