A transformation in the governance structures of English education has been underway since the coalition government came to power, with around 40 per cent of secondary pupils now being taught in an Academy school. Interestingly, patterns of party politics at the local level are a good predictor of whether individual schools will opt into Academy status. This suggests party political conflict over the control of schools, writes Tim Hicks. School governors, it seems, can actually act in rather political ways.

A transformation in the governance structures of English education has been underway since the coalition government came to power, with around 40 per cent of secondary pupils now being taught in an Academy school. Interestingly, patterns of party politics at the local level are a good predictor of whether individual schools will opt into Academy status. This suggests party political conflict over the control of schools, writes Tim Hicks. School governors, it seems, can actually act in rather political ways.

The way schools in England are governed is undergoing a dramatic transformation. The previous model, in which most schools were administered and controlled by a combination of Local Education Authorities (LEAs), the national Department for Education (DfE), and local school management, is in the process of being swept away under the auspices of a wholesale roll-out of the “Academies” programme. By January of 2012, the proportion of secondary pupils being taught in an Academy school had jumped to almost 40 per cent – and the nearly decade-old, Labour-instigated, sponsor-led Academy scheme accounted for less than a quarter of this figure.

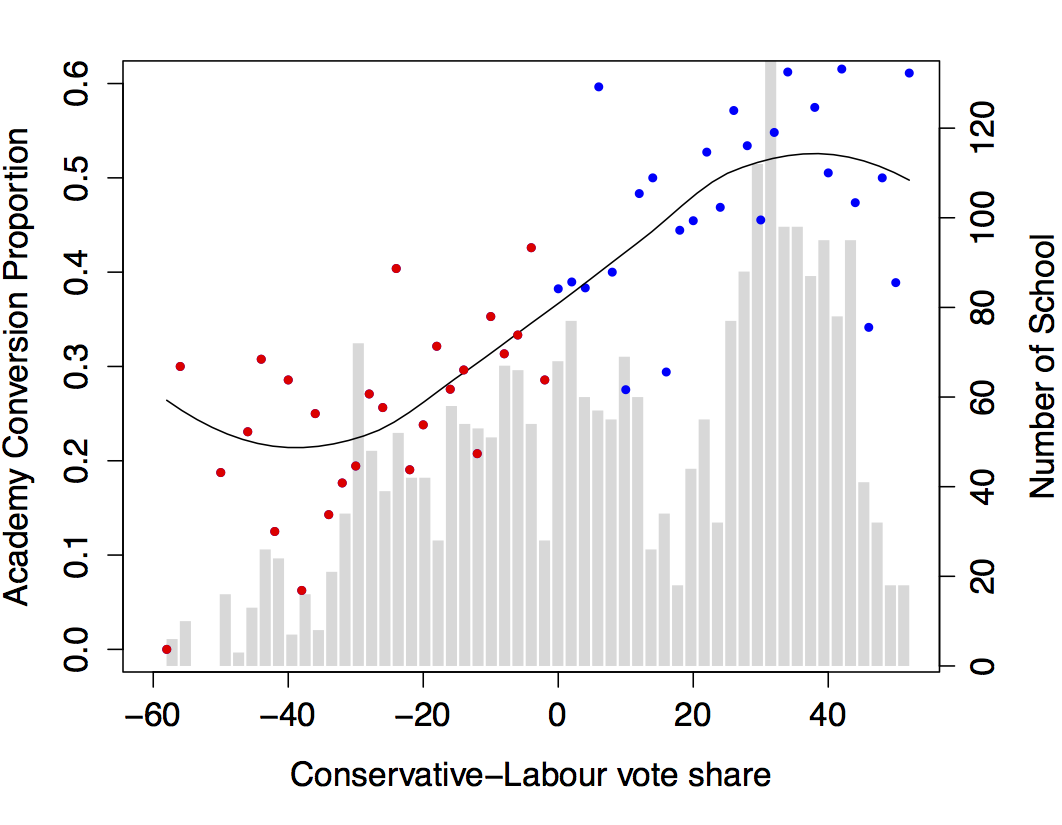

At the national level, the coalition government has been remarkably successful at converting schools to Academy status, then. However, this success has not been uniform across all areas. What’s more, patterns of party politics at the local level are a good predictor of whether individual schools will opt out of LEA control and into Academy status. This is clear when comparing schools in Labour-held parliamentary constituencies, where only around 25 per cent have converted, to those in government-held constituencies, where around 50 per cent have converted. Figure 1 also depicts this relationship, connecting the electoral strength of parties (measured as Conservative-minus-Labour 2010 vote share for the constituency of each school) with Academy conversion more broadly.

Figure 1: Proportion of schools converting to academy status (January 2013), by relative Conservative constituency-level electoral strength in 2010

Note: Histogram in grey uses right axis.

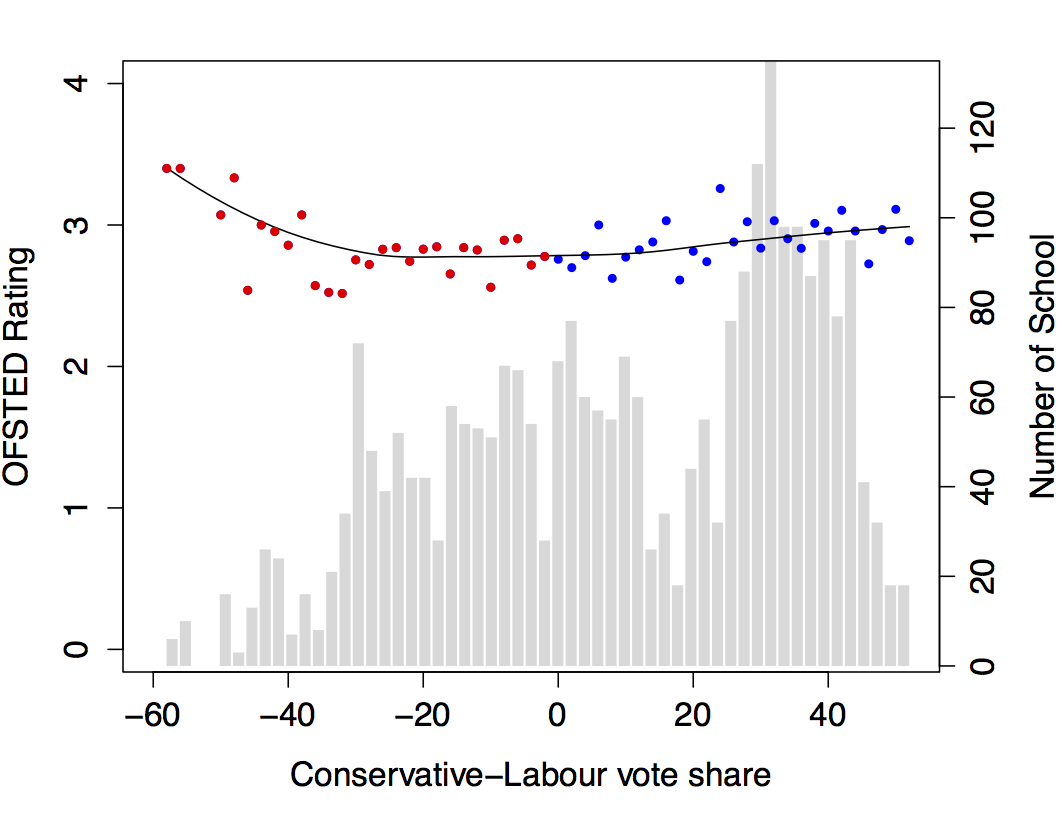

How can we make sense of this political pattern? We can rule out a number of possibilities straight away. First, while the DfE have used OFSTED ratings to help decide whether to allow schools to convert, it is not the case that schools in Labour-held areas have lower OFSTED ratings. This can be seen clearly in Figure 2, which plots average OFSTED ratings against the same Conservative-minus-Labour 2010 as in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Average OFSTED ‘overall’ inspection rating by relative Conservative constituency-level electoral strength in 2010

Note: Histogram in grey uses right axis.

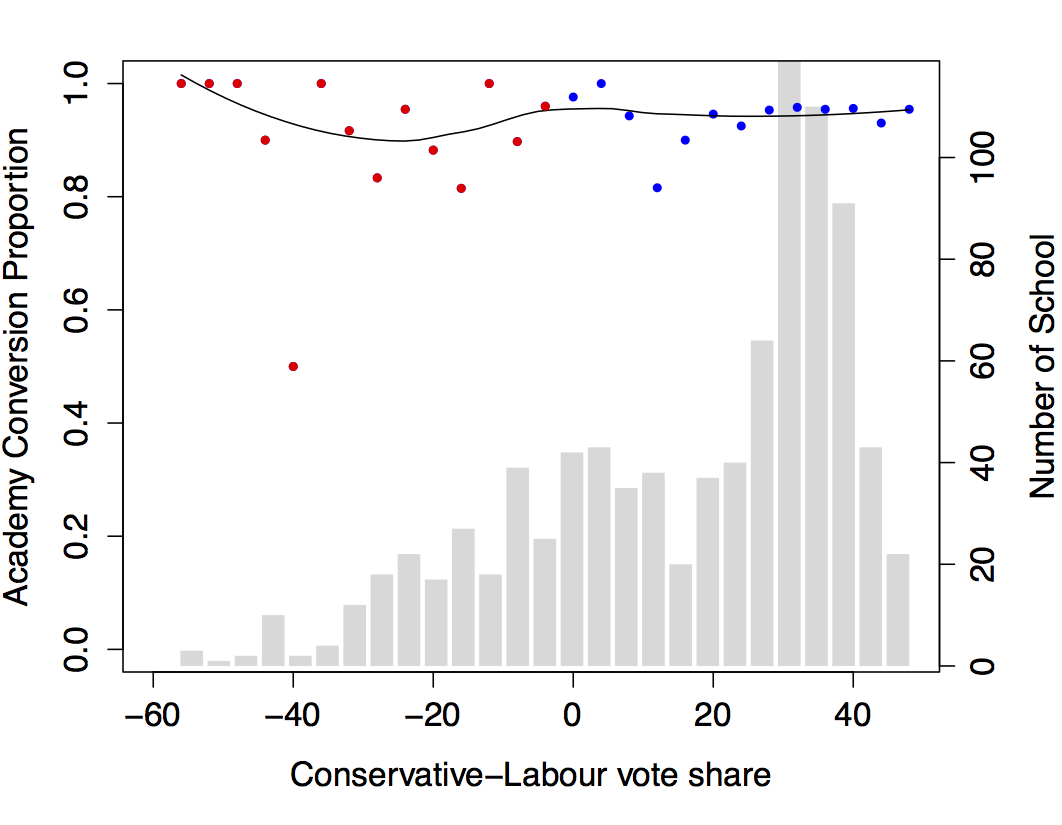

Second, we can rule out bias on the part of the DfE in the process of authorizing conversion. Data from the DfE, and processed by The Guardian, means that we know which schools expressed an interest in converting their status, as of around July 2010. While this was very early in the process, 931 out of a total of around 2700 schools said they were interested in converting. Furthermore, as figure 3 shows, there is essentially no political pattern to the probability that these “interested” schools subsequently converted. On the contrary, the story is about just how likely it was that the DfE would authorize conversion.

Figure 3: Proportion of schools expressing an interest in Academy conversion (July 2010) that subsequently converted (January 2013), by relative Conservative constituency-level electoral strength in 2010

Note: Histogram in grey uses right axis.

It follows from all this that the strong political pattern to conversions is driven from the school side, not the DfE side. The relevant question becomes: what explains which schools are interested in converting in the first place? We can answer this question with statistical analysis. Figure 4 shows how the probability of conversion-interest varies with the political orientation of a school’s parliamentary constituency. The statistical model that underlies the figure accounts for the size of the school, as well as the proportion of students entitled to receive free school meals (which is a standard metric of social need). Thus, what we see can reasonably be thought of as the political effect. The figure shows a positive relationship between Conservative electoral strength and conversion probability across schools of all three major OFSTED ratings.

Figure 4: Predicted probability of schools expressing interest in Academy conversion as a function of the Conservative-Labour vote share, for each of ‘Outstanding’, ‘Good’, and ‘Satisfactory’ OFSTED ratings

Note: 90 per cent confidence intervals shown in transparent colours. Other predictors held at their sample means.

Exactly why this effect should arise is difficult to ascertain. Perhaps the most plausible explanation is that school governors tend to be drawn from their local political milieu. For this reason, they tend to have political orientations that accord with broader voting patterns in their areas. There may be ideological affinities between the Academy scheme and more right-wing political thought, perhaps in terms of beliefs about the extent to which schools should be free to govern themselves rather than be controlled by LEAs.

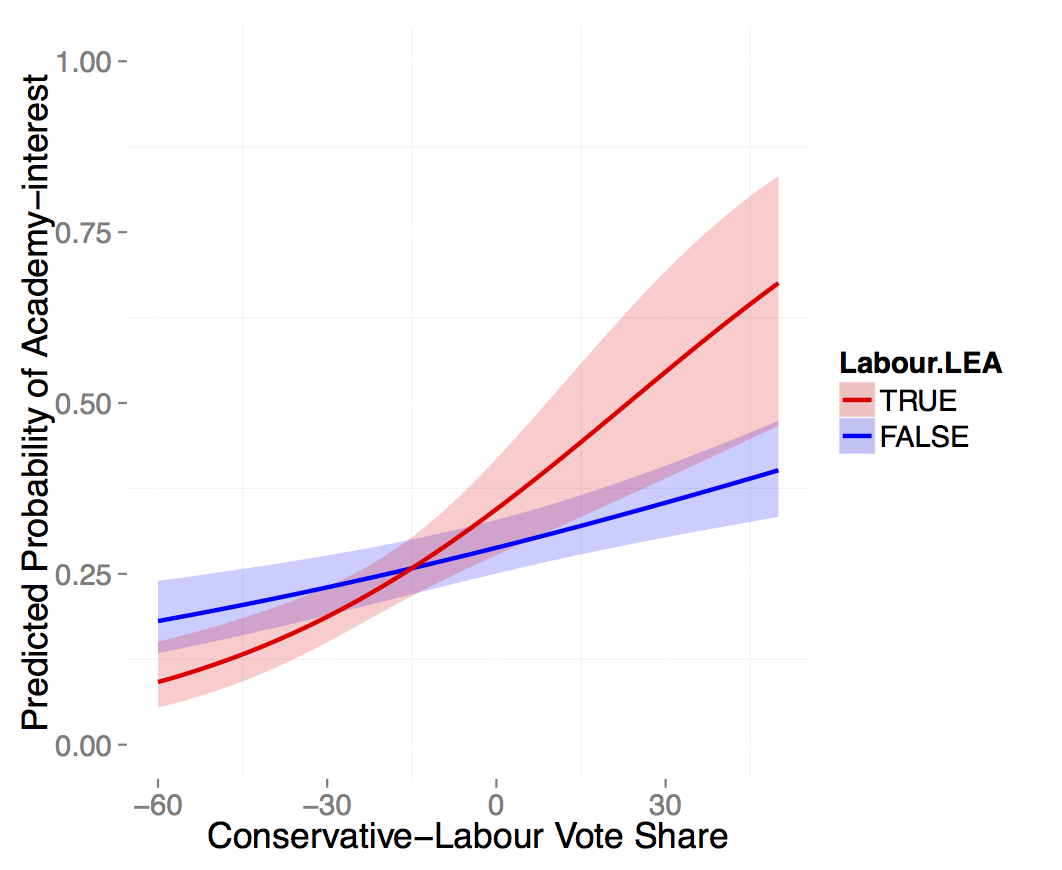

One final piece of evidence suggests that part of the effect is driven by party political conflict over control of schools. Figure 5 shows that the predicted probability of expressing an interest in conversion is conditioned by whether a school’s LEA is controlled by Labour or the Conservatives. Simply, schools in strongly Conservative constituencies, but which happen to fall under the control of a Labour LEA, are especially likely to wish to convert. Meanwhile, schools in strongly Labour constituencies, and that are similarly under the control of a Labour LEA, are the least likely to wish to convert. It appears that school governors that have political disagreement with their LEA are much more likely to want to gain their independence.

Figure 5: Predicted probability of schools (rated ‘Good’ by OFSTED) expressing interest in Academy conversion as a function of Convervative-Labour vote share, conditional on being in a Labour-controlled LEA or not

Note: 90 per cent confidence intervals shown in transparent colours. Other predictors held at their sample means.

In sum, there are two stories here. First, the current government is rather successfully transforming the governance structures of the English schooling system. Second, under the surface of this process of transformation, there are marked differences in how it is playing out across different localities. Moreover, these differences provide rather good evidence that notionally apolitical layers of governance – in the form of school governors in this case – can actually act in rather political ways.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Policy Network

Tim Hicks – University College London

Tim Hicks – University College London

Tim Hicks completed a DPhil in Politics at Nuffield College, Oxford. From 2011 until 2014, he was an Ussher Assistant Professor of Political Economy at the Department of Political Science, Trinity College, Dublin. In July 2014, he joins the School of Public Policy at University College London as a Lecturer in Public Policy. Tim’s current research relates to three areas. First, a project on the politics of schooling – especially regarding issues of school choice and private provision. Second, a collaborative project with Alan Jacobs (University of British Columbia) and Scott Matthews (Memorial University, Newfoundland) on how economic inequality can lead to political inequality. Third, a collaborative project with Lucy Barnes (Kent) on the impact that the financial crisis had on political attitudes. He blogs at http://tim.hicks.me.uk/.