Snap elections are an increasingly common occurrence in parliamentary democracies, but do these disruptions to the electoral calendar have consequences for voters’ trust in politics? Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte presents novel evidence from the 2017 snap election to show that voters are, on average, more trusting of government when provided with early summons to the polls.

Snap elections are an increasingly common occurrence in parliamentary democracies, but do these disruptions to the electoral calendar have consequences for voters’ trust in politics? Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte presents novel evidence from the 2017 snap election to show that voters are, on average, more trusting of government when provided with early summons to the polls.

Snap elections – those triggered by incumbents in advance of their original date in the electoral calendar – are a common feature of parliamentary democracies. In 2021, Canadian Liberal party Prime Minister called early elections asking ‘who wouldn’t want a say? Who wouldn’t want their chance to help decide where our country goes from here?’ Appeals to the electorate to ‘have their say’ are rationales for early elections that, despite opportunistic motivations behind early polling dates, present them as democratic provisions that inspire political trust. A rational interpretation for citizens when openly invited to endorse or reject an incumbent’s mandate is that the incumbent is acting in accordance with democratic expectations: if a politician is willing to face the court of public opinion, then they have nothing to hide.

At the same time, however, snap elections are often opportunistic and brought about because of an incumbent’s advantageous polling or economic position. Voters, likely exposed to punditry highlighting the strategic motivations of the incumbents, may equally react negatively to early summons: if a politician is rigging the game to their advantage, then they are not trustworthy.

Faced with these alternative theoretical arguments, I ask: how do snap elections influence political trust? In a new study, I use a quasi-experimental research design to argue that calling early elections can induce an increase in political trust. Taking the concrete case of Theresa May’s shock announcement in 2017 to go the polls, I show that opportunistic snap elections can increase political support because citizens react positively to being granted the opportunity to have their say.

May’s gamble: a natural experiment

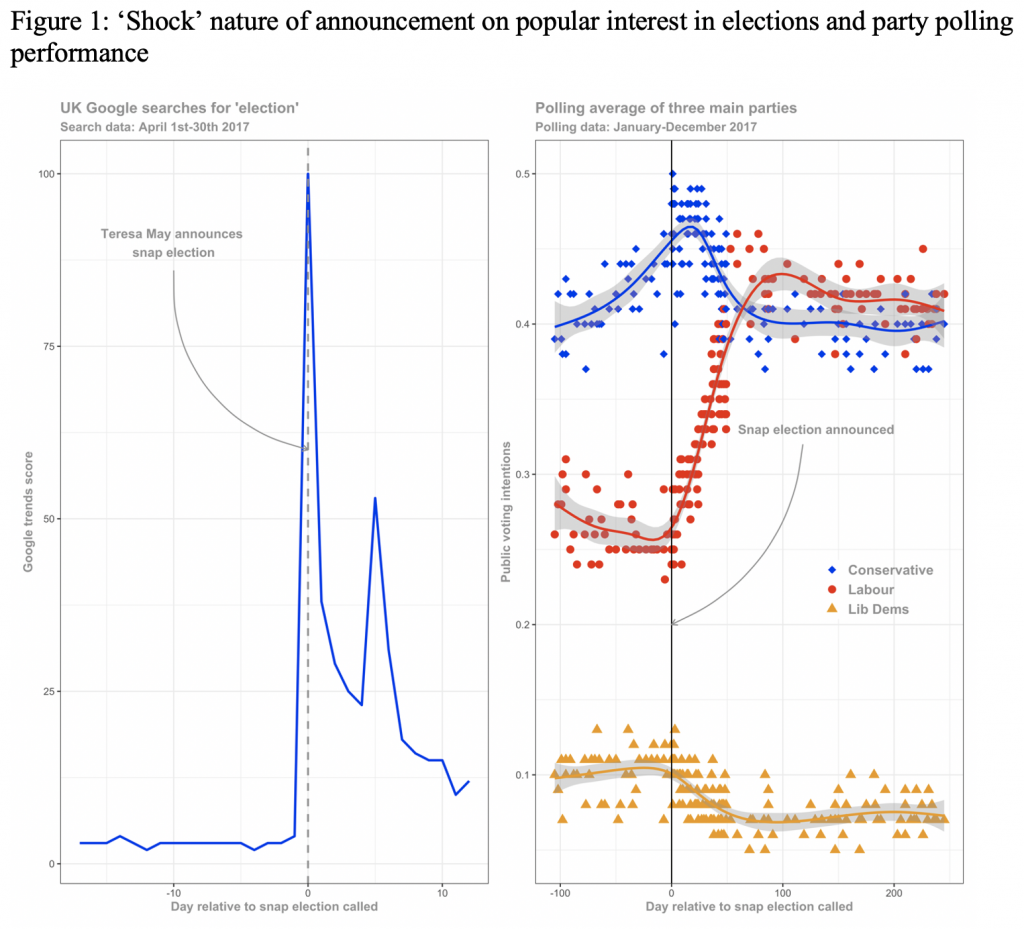

The experimental design relies on the coincidental timing of the fieldwork for the Eurobarometer survey and May’s surprise announcement of an early general election. Given the announcement was unexpected (Figure 1), individuals being interviewed by the Eurobarometer are naturally – as good as randomly – assigned into one of two groups: control and treatment. Those in control were interviewed in the days immediately before early elections were announced whilst those in treatment were interviewed in the days immediately after. Comparing the demographic makeup of these two groups (e.g. gender, age, partisanship, Brexit vote) demonstrates that the two groups are symmetrical and, as a result, we can be confident that any divergence in levels of political trust between the two groups is caused by the naturally occurring discontinuity in information regarding the early election.

Do snap elections increase trust?

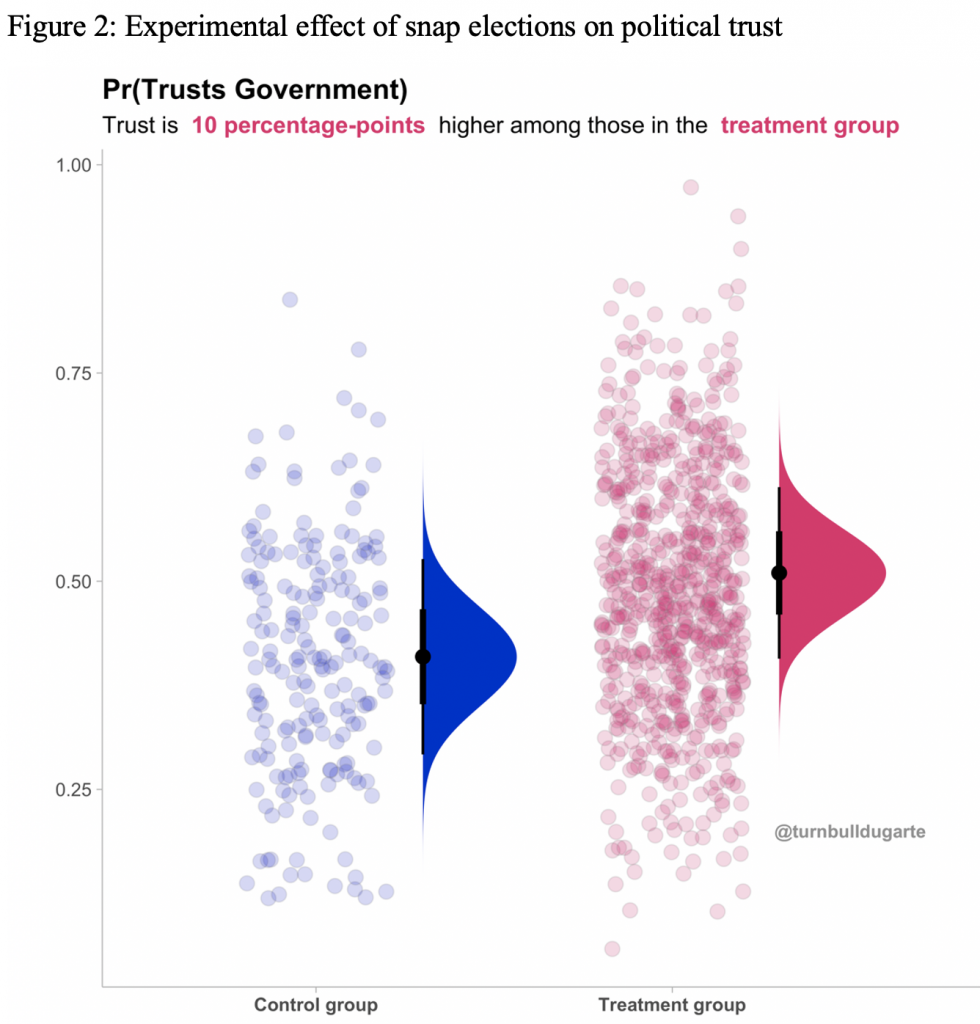

The main findings of the quasi-experiment are visualised in Figure 2. Snap elections can increase political trust. Comparing the probability of trusting the government amongst those naturally assigned to control and treatment conditions, there is a significant increase in trust enjoyed by those in treatment. The effect of early summons to the polls on trust is large, at 10 percentage points. Given the low levels of trust in the control group (39%), a ten percentage-point increase is far from trivial at 25%.

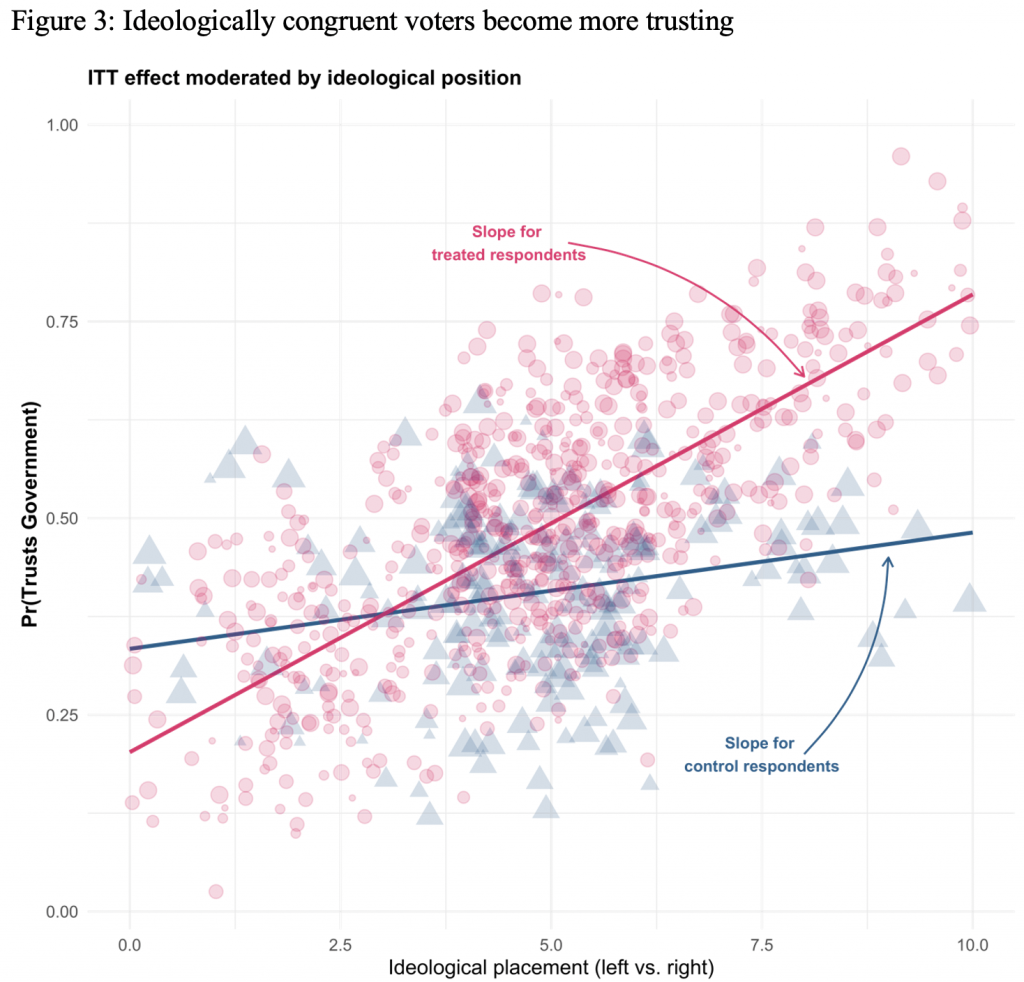

Testing for the conditional of the treatment effects – were some individuals more likely to become more trusting than others? – I find that the majority of movement comes from those who hold ideological positions congruent with the (Conservative) incumbent. Those who identify on the right (Figure 3) as well as those who identify as ‘Leavers’ are significantly more inclined to update their trust evaluations rather than left-wing individuals or ‘Remainers’. This is not surprising. May’s 2017 gamble was brought about, in part, to provide her with a mandate to ‘crush the [Brexit] Saboteurs‘, providing those with pro-Brexit sympathies the opportunity to ensure that their Brexit preferences were communicated at Westminster.

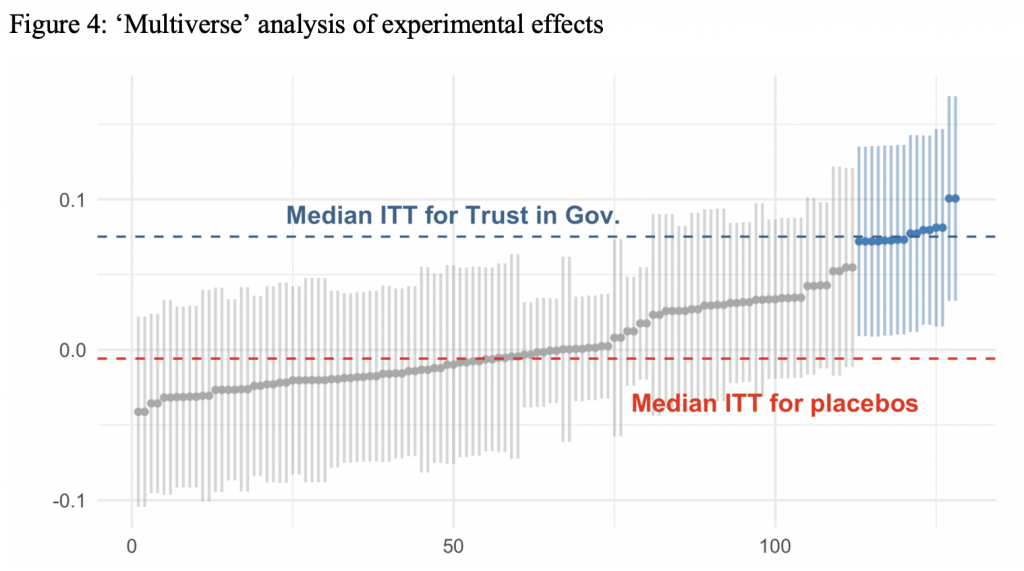

The results of the quasi-experimental research design are robust. To demonstrate this, I present a multiverse analysis in which the results are presented based on a variation of different specifications, subsamples, and placebos. Across these different analytical ‘universes’ shown in Figure 4 (more details here), the median result of treatment exposure on trust is largely symmetrical and consistent (dashed blue line) whereas treatment plays no role on different placebo outcomes (dashed red line) such as trust in the media or life satisfaction.

Reflections on the gamble

May’s gamble did not pay off. Bucking the trend in the evidence that suggests snap elections can indeed provide net gains for incumbents, May’s opportunistic manoeuvre resulted in a net loss for her party in terms of seats which, ultimately, cost her an outright majority in the House of Commons. May’s gamble did, however, provide some, at least short-term, dividends for political trust. Given ongoing concerns regarding the apparent widespread decline in political trust, exasperated by events like partygate, one implication of our findings is that incumbent opportunism in the form of snap election, whilst taken for strategic gain, may in fact aid in alleviating political discontent. When the electoral calendar is distorted and citizens are called to the polls to express their (dis)content with the incumbent, the effect is, on average, remedial to political trust.

____________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in the European Journal of Political Research.

Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Southampton.

Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Southampton.