In December 2020, the RSA polled the UK public on their economic security, values, political outlook and policy preferences. Using cluster analysis, they created seven ‘snapshots’, based on the values and economic security of different groups. Will Grimond introduces the three most insecure groups identified.

In December 2020, the RSA polled the UK public on their economic security, values, political outlook and policy preferences. Using cluster analysis, they created seven ‘snapshots’, based on the values and economic security of different groups. Will Grimond introduces the three most insecure groups identified.

Precarity is one of the defining features of the 21st century economy. The issue has been thrust into the political limelight in recent years, as progressives look to deal with a problem which is impacting their key constituencies, and creating new, unfamiliar groups. Conversations around the direction of the Labour party have focused on economic security – evident in the never-ending conversation on how to win back elusive ‘red wall’ voters. Joe Biden’s 2020 campaign also focused heavily on areas with high levels of poverty, and on the shrinking American ‘middle class’ as a changing job market, rising costs of living, and economic precarity reach higher up the food chain.

Economic insecurity is rife in the UK – a quarter of us would struggle to pay an unexpected bill of £100. The term is distinct from traditional understandings of poverty and inequality in that it aims to encapsulate the experience felt by those barely keeping afloat – those who ‘just about manage’ – and also seeks to consider the whole range of impacts which manifest from financial difficulty. Economic security is as much a measure of wellbeing and mental health as it is one of assets and income.

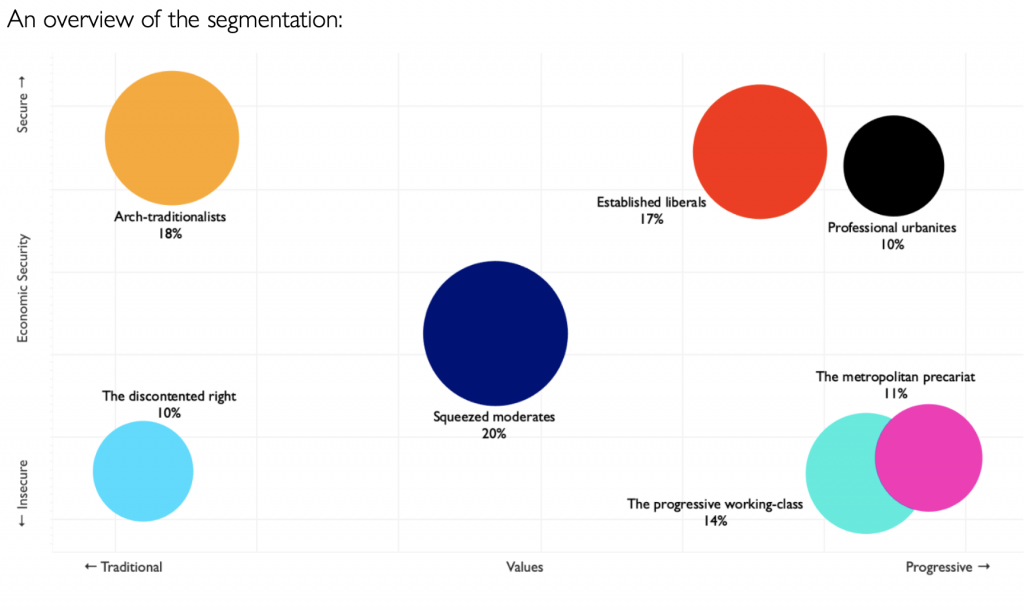

To better understand how economic insecurity is affecting the UK population, we carried out a segmentation exercise, looking both at determinants of economic security and the values of the public. Values tell us a lot – understanding different value groups is useful from a party-political perspective, and also allows us to consider how different policy interventions might be received. We asked questions on societal issues like diversity, the importance of tradition, and care for the environment – and personal ones, such as their perceived class attributes and level of optimism.

Our findings suggest that economic security has varied impacts for different groups. The three most insecure groups that we identified – which we have termed the metropolitan precariat, the progressive working class and the discontented right – each suffer precarity in different ways.

The metropolitan precariat complain of high housing costs, arduous working hours, and fluctuating paycheques. They are the youngest of all of our groups, with the highest proportion of BAME, and they are an urban and relatively high-income group. The discontented right, meanwhile, are more middle-aged. They suffer from extreme financial difficulties – over two-thirds would struggle to pay an unexpected bill of £100, and over half are in worrying levels of debt. They have higher levels of unemployment, complain of a lack of job security, and hold highly traditional views on a range of issues. Our final insecure group, the progressive working class, are likely to be more rural. Their concerns centre on the lack of opportunity in their local areas, and they would like to see the government reduce regional inequalities.

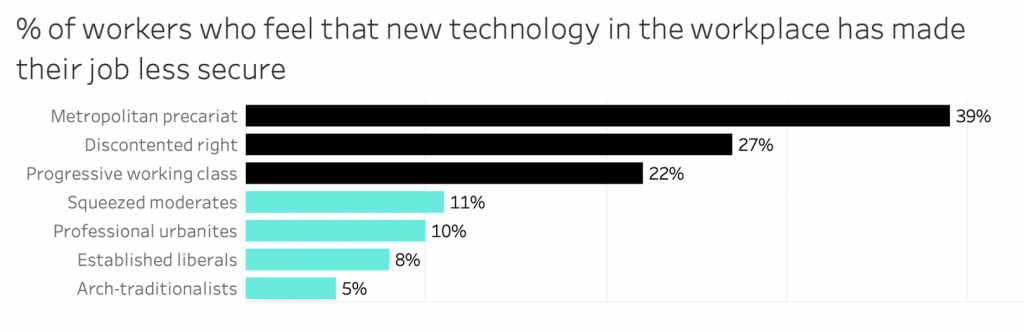

These segments are also the most at risk from having their jobs automated – our economically insecure groups are the most likely to say that new technology is a threat to their job. Automation may have accelerated during the pandemic, as firms look to replace their now-vulnerable human capital; research has found that lower-paid jobs are at the highest risk of being replaced by robots.

Politically, there is no easy roadmap to building a coalition between all three of these groups. They have very different opinions on issues like diversity, feminism, and the importance of British values, and an appeal to values may struggle to meet those of all three. There are also significant differences in their approach to politics and economics – the discontented right, for instance, are among the least likely to want to increase taxes to expand the welfare state, while the metropolitan precariat are strongly in favour.

These findings also highlight the challenges faced by young people: of our two young groups, one faces extreme precarity, the other financial surety, steady incomes, and good job prospects. These groups are both among the most likely to be in full-time employment, but one group is not being rewarded for their efforts, and face issues like fluctuating paycheques and excessive working hours. The other, meanwhile, enjoys a stable income, high rates of home ownership, and opportunities for career progression.

Despite this, there are commonalities between Britain’s new tribes. There is consensus on issues like meeting our climate targets and including citizens more in the political process. There are also signs of solidarity – all agree that today’s young people have a harder time financially than previous generations, for instance.

And there are things that can be done to tackle precarity. The issues faced by the progressive working class speak to concerns about economic agency and place: devolving welfare policy could be a step toward ensuring that economic policy is better tailored to local and regional communities. A focus on ‘good work’ – which has fallen off the agenda in the current government – will be crucial to making sure our younger precariat have the in-work support they need. Providing a living wage and putting a stop to intrusive workplace monitoring would be first steps.

This should come with a renewed emphasis on job security, especially as industries are hit with the twin threats of automation and COVID-19-related lockdowns. Economic insecurity will continue to grow as economic and technological change pushes previously secure groups to the margins, and policymakers will have to navigate a widening gap in the values of the public. But there are things that can be done, now, to tackle precarity in the UK – and as we come out of the pandemic, the case has never been more urgent.

_____________________

Will Grimond is media and communications officer at the Royal Society for Arts.

Will Grimond is media and communications officer at the Royal Society for Arts.