Trust in government is at an historic low. Yet levels of local trust in certain local areas in England that had strategically prioritised social cohesion before the pandemic have remained stronger than elsewhere. Jo Broadwood, Fanny Lalot, Dominic Abrams and Kaya Davies Hayon write that this may be reflecting the strength of relationships that were developed via local social cohesion programmes. These relationships could then be relied on as communities mobilised to support and protect the vulnerable during the COVID-19 crisis, further strengthening and deepening those connections.

With over half of the population vaccinated and with restrictions easing, the government has signalled its intention to deliver on its 2019 election promise of ‘levelling up’: it has appointed Neil O’Brien MP as the Prime Minister’s adviser on the issue and has committed to a White Paper later in 2021. With the pandemic having revealed long-standing structural and regional inequalities, recovery is going to take a long time and place is going to play a vital role in recovery efforts. Concentrating on economic regeneration and recovery in ‘left behind’ places is therefore long overdue.

As a result of our research on the impact of COVID-19 on societal cohesion, we would argue that as well as investing in infrastructure, transport, employment, and business, the government should also pay attention to strengthening the social fabric and social cohesion in particular. Because it is this social fabric – a combination of strong trust in local institutions, and strong and trusting connections between different groups and communities – that can directly contribute to creating a sense of pride in the local place and a collective vision of it as a ‘good place’ for people to live, work, raise families, and grow old in. As such, social cohesion can play a vital role in revitalising and re-energising local places.

In developing the new agenda, government would do well to look at the success of one of their own recent place-based schemes. Our research has compared the experience of people from local areas that had previously invested in social cohesion via the government’s Integration Area programme with that of people from other places with monthly surveys over the course of 2020.

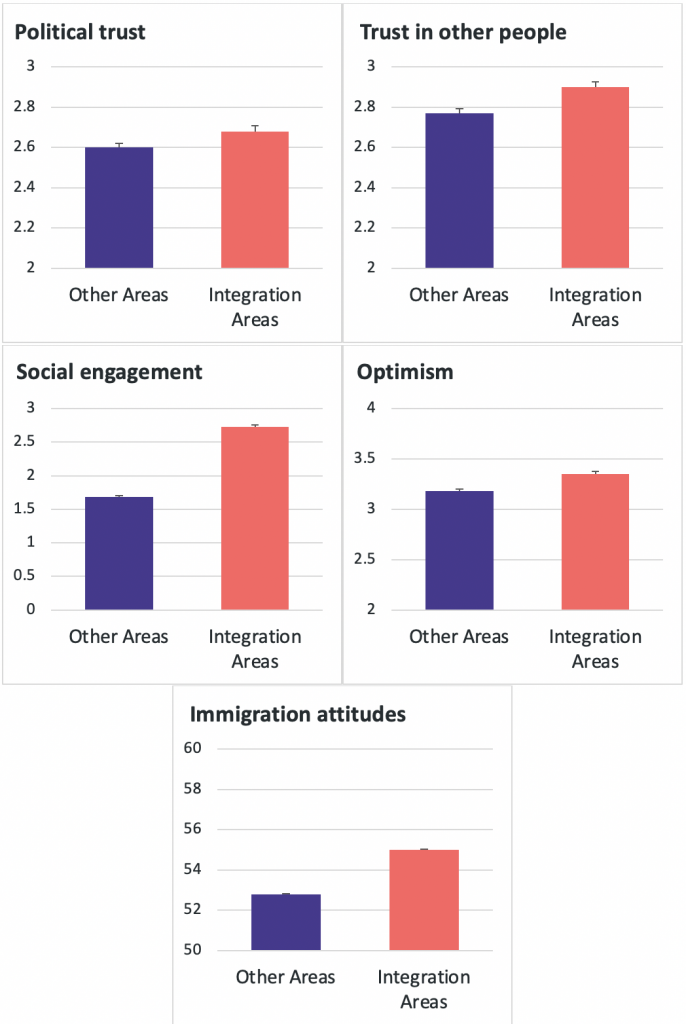

Surveying over 2,900 people, results from the June/July 2020 survey showed that respondents from the Integration and Cohesion local areas experienced higher levels of trust in the government as well as trust in other people in general (to respect COVID-19 restrictions). They also reported greater social engagement, with residents twice as likely to volunteer as elsewhere in the UK. These areas also sustained higher levels of optimism, more positive relations between different groups and towards people from migrant backgrounds in particular – despite four of the six areas having higher rates of infection and longer lasting restrictions for most of the pandemic (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mean scores of political trust; trust in other people to respect COVID-19 restrictions; social engagement, immigration attitudes; and optimism for the future for respondents from the Integration and Cohesion local Areas and respondents from Other Areas, June/July 2020.

Notes: Means are estimated marginal means, controlling for demographics (age, gender, ethnicity, income, subjective socioeconomic status and political orientation). Political trust, trust in other people, and optimism were measured on 5-point Likert scales. Social engagement shows the number of actions respondents reported engaging in during the previous month (up to 14 possible actions, including volunteering, donating, signing a petition, boycotting, demonstrating, supporting a social media campaign, etc.). Immigration attitudes were measured on a 100-point ‘feeling thermometer’ with greater scores indicating warmer or more positive attitudes.

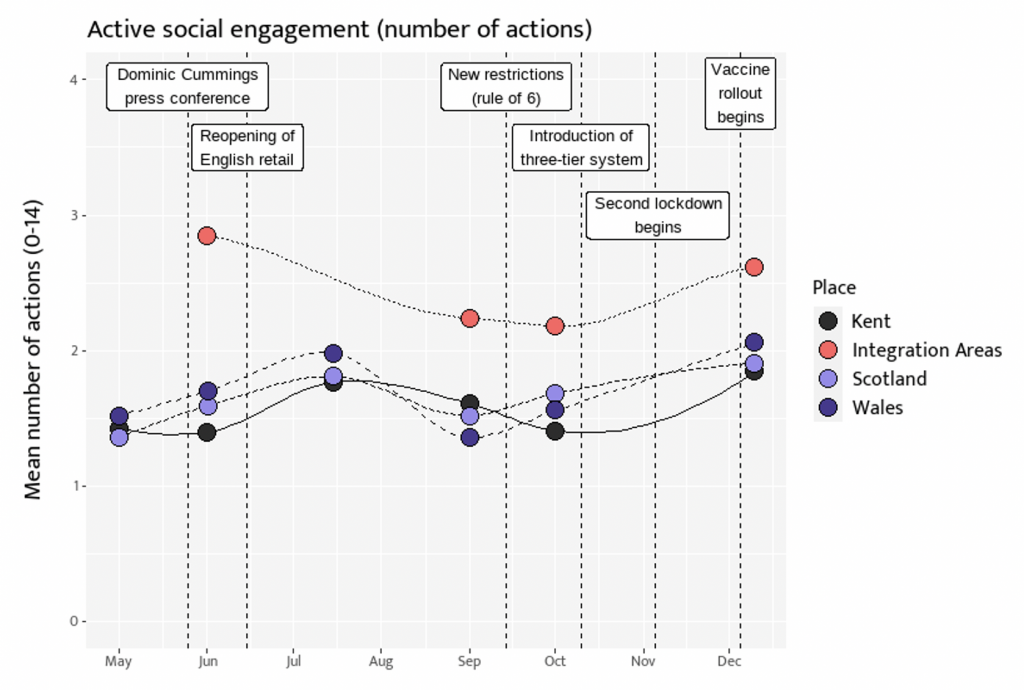

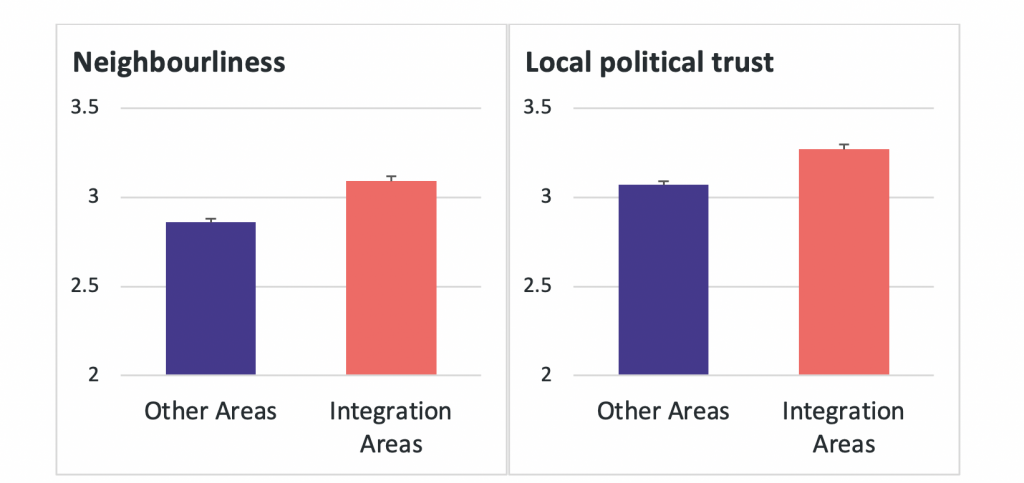

Subsequent results confirmed that the Integration and Cohesion Areas maintained a greater sense of social cohesion throughout the year. Notably, results from the December 2020 survey (including over 2,800 respondents) showed respondents from these areas continued to express higher trust in the government and in other people in general, and reported greater social engagement (Figure 2). They also reported higher and sustained neighbourliness (or sense of good relations in one’s local area). Finally, and importantly, they expressed greater trust in their local government’s response to COVID-19 than respondents from other areas (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Active social engagement (number of actions respondents said they have done during the past month) from May to December 2020, in the Integration and Cohesion Areas and in Other Areas (Kent, Scotland, and Wales).

Note: Social engagement shows the number of actions respondents reported engaging in during the previous month (up to 14 possible actions, including volunteering, donating, signing a petition, boycotting, demonstrating, supporting a social media campaign, etc.).

Figure 3. Mean scores of local political trust (trust in the local government’s response to COVID-19) and neighbourliness for respondents from the Integration and Cohesion local Areas and respondents from Other Areas, December 2020. Note: Neighbourliness and local political trust were measured on 5-point Likert scales.

Note: Neighbourliness and local political trust were measured on 5-point Likert scales.

In order for levelling up to be successful, it will be crucial to take a place-based approach. This will mean understanding the interrelationship of demographics, history, social relations, local economy and business, geography, transport, housing and education, and social cohesion. Social cohesion sits at the heart of getting things done locally. It is best described as a bank of local trust and social connections that needs to be consistently maintained in order to be drawn on in times of crisis and change.

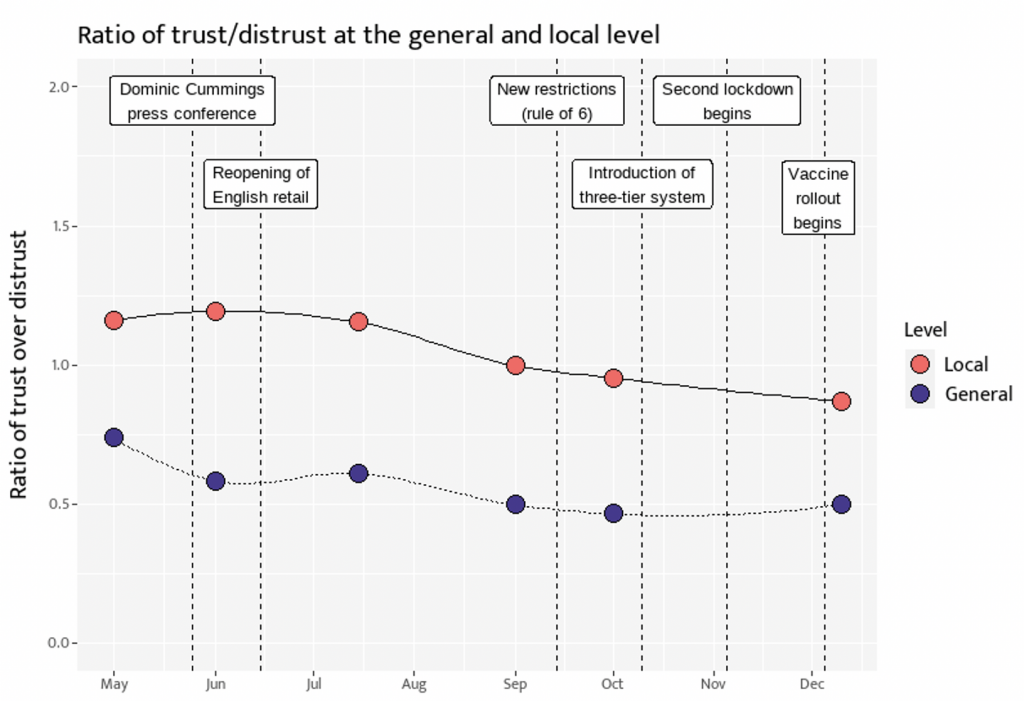

The six local areas we surveyed (Bradford, Blackburn with Darwen, Calderdale, Walsall, Waltham Forest and Peterborough) had all invested in embedding principles of social cohesion in their strategy and programmes in the years preceding the pandemic. Our research shows that throughout the pandemic, levels of trust, particularly local trust, in those areas have been more resilient than elsewhere. In the early days of the pandemic, this meant faster and more effective community organising and responding, with local government and services working hand in hand with local communities to deliver support to the vulnerable, targeted public health messages, and successful test-and-trace schemes. Trust in local communities and towards the government will continue to play a huge role as the vaccination programme is embedded and restrictions are lifted, and in the longer-term recovery.

Figure 4. Ratio of political trust and distrust at the general (UK) level and the local level from May to December 2020, in the Integration and Cohesion Areas and in Other Areas (Kent, Scotland, and Wales).

Notes: The figure shows the relative proportion of people trusting versus distrusting across time (numbers above 1 indicate that a higher proportion of people felt trust or high trust while numbers below 1 indicate that a higher proportion of people felt distrust or high distrust. 1 represents that an equal proportion of people felt trusting and distrusting 1/1 ratio).

So, what did these areas do? In our recent policy and practice paper we identify ten shared principles that characterised their approach in areas that were very different from each other both demographically and more broadly. Each of the six local areas grounded their programmes in crucial knowledge from local people in order to respond to the distinct and unique challenges and opportunities in that place. They developed a shared vision about their locality, engaging across all communities and groups. Their approaches included strong and representative leadership; tackling barriers to inclusion of underrepresented groups and minority communities, including addressing hate crime and prejudice; embedding principles of social mixing; promoting trust through bridging work; and encouraging volunteering. They invested in cross-sector partnerships engaging with local and national business to support skills development and employment opportunities.

We now know from our findings that investing in social cohesion works in terms of building trust between groups and individuals, and between citizens and their local and national institutions. As the British Academy’s recent report points out, the UK is at a crossroads as we emerge from the pandemic. British society is still vulnerable to the divisions and polarisation that were present in the years preceding the pandemic. Brexit is likely to impact different regions unevenly and the devolution debate is accelerating. We need to strengthen the ties that bind us and in particular those ties that bridge between different groups, communities, and regions.

Trust in our institutions and government and trust in each other are vital elements of social cohesion and indeed are essential to the successful functioning of our democracy. From the vaccine rollout to engaging diverse groups and communities in recovery efforts, to mitigating the impact of the pandemic on mental health and loneliness, to levelling up, strengthening trust and social connection will be vital on the road to recovery.

The government must build on the learnings from their own Integration Area programme and work in partnership with local government to support a locally-tailored place-based approach that puts social cohesion at the heart of its levelling up agenda.

_______________________

Note: the above draws on findings from the latest report of the Beyond Us and Them Research Project, a partnership between Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network and the University of Kent, funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

Jo Broadwood is Chief Executive of Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network. Previously, Jo was CEO of StreetDoctors where she grew a UK wide healthcare volunteering movement advocating for a public health approach to address youth violence.

Fanny Lalot is Research Associate in the School of Psychology at the University of Kent.

Dominic Abrams is a Professor of Social Psychology and the Director of the Centre for the Study of Group Processes in the School of Psychology at the University of Kent.

Kaya Davies Hayon is Research and Development Manager at Belong. She holds a PhD in cultural studies from the University of Manchester and worked in academia for a number of years before joining Belong.