A ten-year project of English landscape reform appears an indeterminate mess, and COVID uncertainty has led to calls for delay. But ‘muddling through’ may turn out to be the best strategy to deliver change to reset the relationship between people, food and nature post-pandemic — if three vital ingredients are in place, says Tony Hockley.

A ten-year project of English landscape reform appears an indeterminate mess, and COVID uncertainty has led to calls for delay. But ‘muddling through’ may turn out to be the best strategy to deliver change to reset the relationship between people, food and nature post-pandemic — if three vital ingredients are in place, says Tony Hockley.

The root cause of the pandemic lies in the relationship between humans and other species, and its impact has highlighted the need for better connections to nature. Public policies to tackle the climate and biodiversity crises will be central to recovery plans. At the same time, England is experimenting with new systems to transform the way the landscape is managed after leaving the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy. It is not just an experiment in major public policy reform, but also in extensive behaviour change.

There are two standard approaches to public policy reform. One is the ‘heroic’ approach in which the policymaker sets out to dictate the path towards a fixed goal. By its nature, this approach does not require a shared belief that reform is required. The second is the ‘cowardly’ approach, in which they do the minimum necessary to create an illusion of headline change without facing the major issues involved. This is often the forced response to a situation in which the need for reform is widely accepted but politically risky. Policy heroism tends to be associated with ideology, leading to political polarisation. Top-down reform becomes identified with a particular ideology. This leads in turn to opposition pledges to undo the reform at the next opportunity.

The story of the NHS “internal market” in England came to demonstrate both approaches. It was a heroic change imposed by a Conservative government from 1990. It also saw several illusory changes: Labour pledged to “end” the system in 1997. It did so only in name, and went on to enhance many of the market-based elements.

But many sensitive and complex policy areas have experienced major changes without attracting this degree of acrimony. Often, these developed from initial steps that were so small they were all but invisible to most people, but which initiated a series of incremental changes that eventually led to a complete change of path. (This has much in common with Charles E Lindblom’s observations in his 1959 article The Science of ‘Muddling Through’, albeit in the most strategic form of “muddling with a purpose”.)

One of the reasons Labour could not really “end” the NHS internal market was the popularity of a scheme in which general practitioners could volunteer to hold some of the budget for their patients’ care. In the first year fewer than 300 GP practices joined the scheme. Over six years this number climbed to more than 4000, so that the majority of registered NHS patients were covered by GP fundholding by the time of the 1997 general election. This cautious, incremental approach was more the result of necessity than strategy, with the usual sensitivities around NHS change and high suspicion of the Thatcher administration. Over time, the debate shifted from fear that patients in fundholding practices would suffer as GPs worked within the discipline of fixed budgets, to a fear that these patients were enjoying unfair advantages in access to care. The “two tier NHS’ argument was turned on its head.

The liberalisation of European air transport was a similarly adaptive and incremental process. At first EU Member States were fiercely protective of their (loss-making) “flag carrier” airlines, their power to manage their own transport markets, and to control negotiate international agreements. The EU needed to slowly build its “competence” in cross-border transport within this hostile environment. At first it achieved agreement to liberalise a part of the market that few cared for, allowing new, smaller airlines to create routes between little-used regional airports. Thus began the hugely popular revolution in low-cost air travel. Regulations adapted to experience. If an “heroic” revolution had been forced by diktat, it would either not have happened or would have failed.

Now England’s government is actually planning to take a smarter approach to reform in one of the most all-pervasive areas of policy: farming. As with the NHS and aviation, the details are something of a niche interest, with a relatively small circle of genuine and independent expertise. More than 71% of UK land is farmed, and almost 500,000 people are employed in the sector. The importance to wellbeing, security, and the environment are obvious. There is now wide acceptance that both the climate and biodiversity are in existential crisis. Land management reform has a central role in the response.

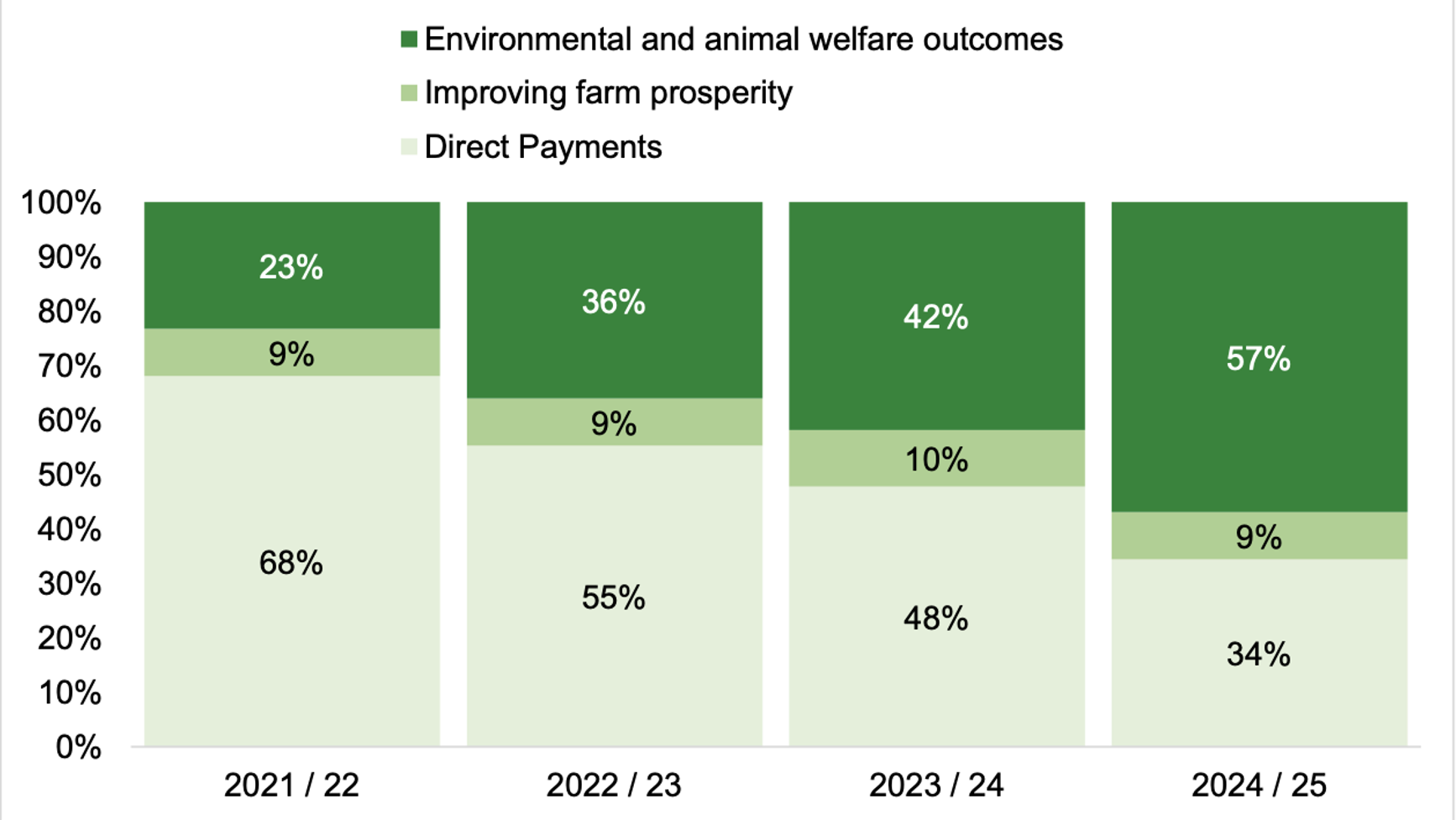

In 2017 the then-environment secretary, Michael Gove, described Brexit as an “unfrozen moment” for change in land management, since it meant Britain would leave the EU Common Agriculture Policy (CAP). This revolution, however, was to be fully funded. The government committed to matching the cash total of EU subsidies for the whole lifetime of the 2017 parliament. The £3.2bn a year financial pledge (£2.4bn in England) was renewed, and thus extended, at the 2019 election. In 2018, the government gave notice of a phased “agricultural transition” to start in 2020, with a gradual shift to a new system of “public money for public goods” by 2028. The change appeared to fit neither the “heroic” nor the “cowardly” model for reform. The commitment to funding and to “pilot” and “test and trial” new approaches seemed particularly generous at a time when other industries were ravaged, some permanently, by the effects of the pandemic and the exchequer embarked on unprecedented emergency spending.

The agricultural transition is, however, highlighting some of the attractions of the more traditional approaches to reform. For governments, the five-year parliamentary term means that results delivered within that timespan are the ones that count. The slow revolution to a new system of “public money for public goods” in agricultural spending, plus the publication of a 25-year “environment plan”, certainly do not fit the usual political timescale. Nonetheless, the plans still create huge personal uncertainty for farmers used to the simplicity of a system that made a bank transfer each year just for occupying land.

Despite the shared ambition for a “green Brexit”, the certainty of the old CAP basic payment scheme remains the anchor against which everything else is judged by those directly affected. That is unsurprising, as these public payments have been the only thing keeping 40% of farms viable. The phased plan had to be adapted, bringing forward a stop-gap funding scheme to fill the growing gap. Some worry that this will be insufficient to settle the storm. Others fear that it may signal a much smaller change of course than the one promised in 2017, and the National Audit Office is concerned that a programme of planned change has become an unplanned muddle.

Figure 1: Phasing out of direct payments (DEFRA, November 2020)

Predictably, the National Farmers Union called for a pause in the phased reduction in direct payments. Nonetheless, some 938 farmers applied to pilot the new systems in September 2021 whilst their Basic Payment Scheme receipts decline. The pioneers came from across the spectrum of farm types, tenures and sizes. Only time will tell whether these pioneers can help embed a culture shift in land management, or simply generate a demand for higher payments to compensate for the loss of habitual income from the public purse.

Research has highlighted the greater priority people give to short-term economic considerations over environmental goals when they make decisions. If incentives do not even cover the direct costs of the desired action, they seem bound to fail. This brings to mind Aneurin Bevan’s description of how he secured the medical profession’s support for the creation of the NHS: he said he had “stuffed their mouths with gold”. Similarly, in the 1990s, GP fundholding needed to be sufficiently attractive for brave pioneers to make the leap, giving confidence to later cohorts. Fundholding GPs who saved money in their prescribing budgets were able to invest in the value of their own premises and in direct patient services. The incentive therefore appealed to both the altruist and egoist within.

The challenge for DEFRA is that it must entice the pioneers to sign up for new schemes, but also ensure that these schemes really do match the principle of “public money for public goods”. Otherwise they risk replicating the CAP. Giving real moral and practical support to the pioneers, and pointing out the early gains from new programmes funded from the phased reductions in direct payments will be important.

In my own research on incremental change in health policy I identified three factors that seem to be necessary for reform to last and grow, achieving a complete break from the previous path.

- Firstly, there must be an acknowledged need for change. This has almost become a given in land management, with widespread acceptance that the climate, biodiversity, and health are in crisis. Indeed, recent polling suggests that the environment is one of the few policy areas today that truly unites the generations. The NFU is arguing to halt reform due to the disruptive effects of the “unfrozen moment” of Brexit that made change possible. COVID has highlighted the inequity of access to nature, declining biodiversity, and the extent to which the UK must be reliant on food (and other) essential imports. The sense of urgency is high.

- Secondly, there must be a small number of free-thinking people willing to show disloyalty to the past. Given the rather limited financial appeal of the new Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI), this group has probably been identified. The low (or negative) rewards on offer indicate either an intrinsic motivation for environmental activities or a desperation to prioritise income over profit. These pioneers need to be supported and celebrated. The next stage, when the scheme is opened to land managers who have not been receiving direct payments, will help to spread enthusiasm and enlarge the ‘tent’.

- Thirdly, there need to be early and visible gains, however small or unexpected. Much of the SFI is focused on increasing knowledge of land and making small changes, such as creating some open spaces within woodland. Defra needs to create opportunities to share early and engaging stories from these initiatives, spreading enthusiasm. Behavioural norms change when people begin to feel they are “missing out” on riding a new wave.

Over time the balance between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation should shift, as the fear of missing out on the new order replaces the fear of losing out on old subsidies. Land management and farming are not easy career choices. There is just as strong a vocational commitment as with the caring professions, often with similarly poor rewards. It is normal to cling on to the here-and-now, however unattractive or unsustainable, for fear of something worse. Even advantageous change will be resisted if it is delivered by coercion. We invent our own cherished “histories” as a means to reinforce our own desired solutions. The very identity of being “a farmer” seems threatened. Only an incremental approach can overcome these natural instincts. I call it “muddling with a purpose”. It may be messy. It may appear indecisive and unclear. It does, however, seem to work better than the standard heroic or cowardly reform models when faced with genuine complexity, genuine human volition, and genuine excitement to make major change happen. A messy approach may just deliver the transformation in the English countryside and nature that would have otherwise stayed in the “too difficult box” and, over time, give some credibility to the “build back greener” rhetoric.

______________________

Note: this post was first published on the LSE COVID-19 blog. Featured image credit: Simon Harrod via a CC BY 2.0 licence.

Tony Hockley is Director of Public Policy at the Policy Analysis Centre and a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Department of Social Policy, LSE. Past roles have included serving as Special Adviser to UK cabinet ministers, Head of Research at a think tank, an expert adviser to the European Commission, and Director of European Public Policy in the headquarters of one of the world’s largest life sciences firms.

Tony Hockley is Director of Public Policy at the Policy Analysis Centre and a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Department of Social Policy, LSE. Past roles have included serving as Special Adviser to UK cabinet ministers, Head of Research at a think tank, an expert adviser to the European Commission, and Director of European Public Policy in the headquarters of one of the world’s largest life sciences firms.