Ian Mulheirn explains why the current policy focus on boosting housing supply does not offer a solution to the housing crisis. Instead, raising the home ownership rate will require further fiscal intervention.

Ian Mulheirn explains why the current policy focus on boosting housing supply does not offer a solution to the housing crisis. Instead, raising the home ownership rate will require further fiscal intervention.

Average house prices in the UK have risen by over 160% in real terms since their low point in the middle of 1996. Home ownership remains around its lowest level for a generation. Among political leaders, policymakers, and commentators there is a broad consensus that these problems are largely down to one failing: decades of undersupply of housing. But the housing shortage story is unconvincing and my new paper for the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence makes the case that a fundamental policy rethink is badly needed.

Housing supply has outstripped household formation for decades

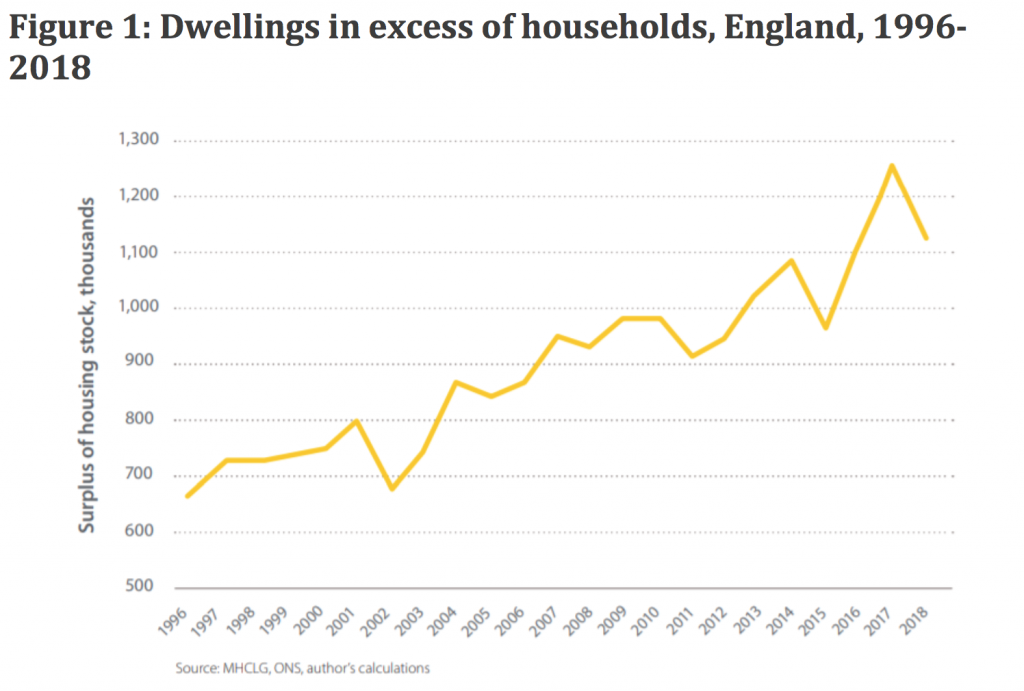

It is commonly claimed that we have failed to build enough houses to meet the demand for places to live. But official data suggest this is not the case: since the 1996 nadir of house prices, the English housing stock has grown by 168,000 units per year on average, while growth in the number of households has averaged 147,000 per year. As a result, while there were 660,000 more dwellings than households in England in 1996, this surplus has since grown to over 1.1 million by 2018 (see Fig. 1). Similar trends are apparent in Scotland and Wales.

It’s possible that the growing surplus of houses nationally could obscure tighter supply at regional level. But here too, the available data suggest that even in London and the South East the number of houses has grown faster than the household count.

The affordability of day-to-day housing costs

Despite the benign picture on housing volumes, it’s important to consider the cost of housing since that affects the rate at which people form new households. Here it is essential to distinguish between the cost of housing services and the price of housing assets. The day-to-day cost of housing services is measured by national statistical agencies around the world by the market rent on a rented house or the equivalent ‘imputed rent’ on an owner-occupied house. This cost can move independently of the purchase price of houses.

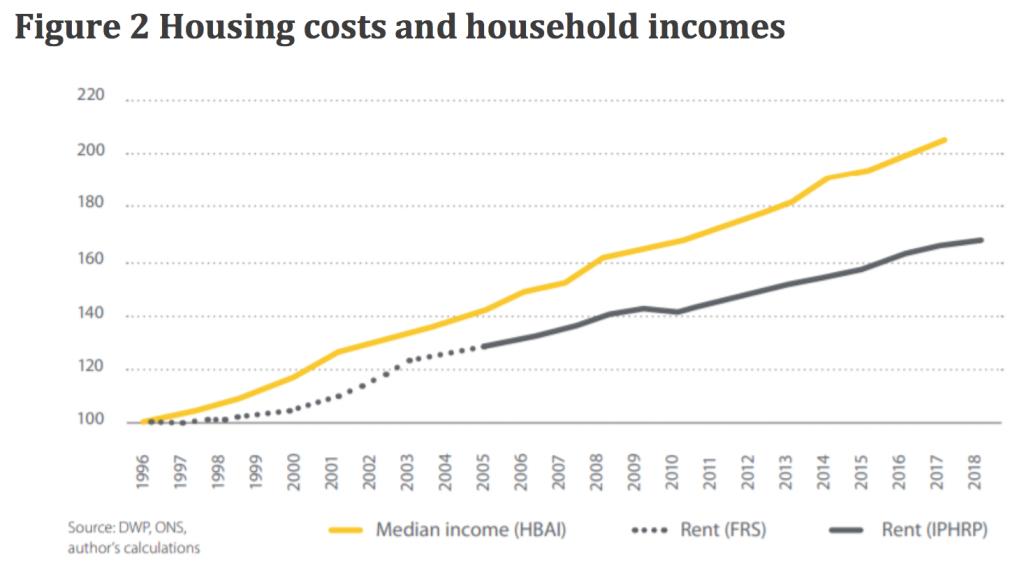

Any shortage of housing should therefore be reflected in rents and imputed rents rising faster than average household incomes. But ONS and Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) data show that rents have risen slower than median household incomes since 1996 (see Fig. 2). Consequently, affordability constraints on households have also eased, on average. Even in London, average affordability appears to have been stable over the past two decades. This is the opposite of what we would expect to see if housing supply had been inadequate and chimes with the evidence of a growing surplus housing stock.

Note: HBAI stands for Households Below Average Incomes; FRS for Family Resources Survey; IPHRP for Index of Private Housing Rental Prices.

Note: HBAI stands for Households Below Average Incomes; FRS for Family Resources Survey; IPHRP for Index of Private Housing Rental Prices.

What has caused prices to boom?

If not a shortage of housing, what lies behind the explosion in UK house prices from around 4.5 times median household income in 1996 to a multiple of around eight today? The established theory of house price formation tells us that changes are determined by a combination of market rents and the cost of capital. So house prices can jump or crash in response to shifts in the main components of the cost of capital: mortgage interest rates, taxes, and expectations of future price growth. Such volatility can occur even when rents are stable.

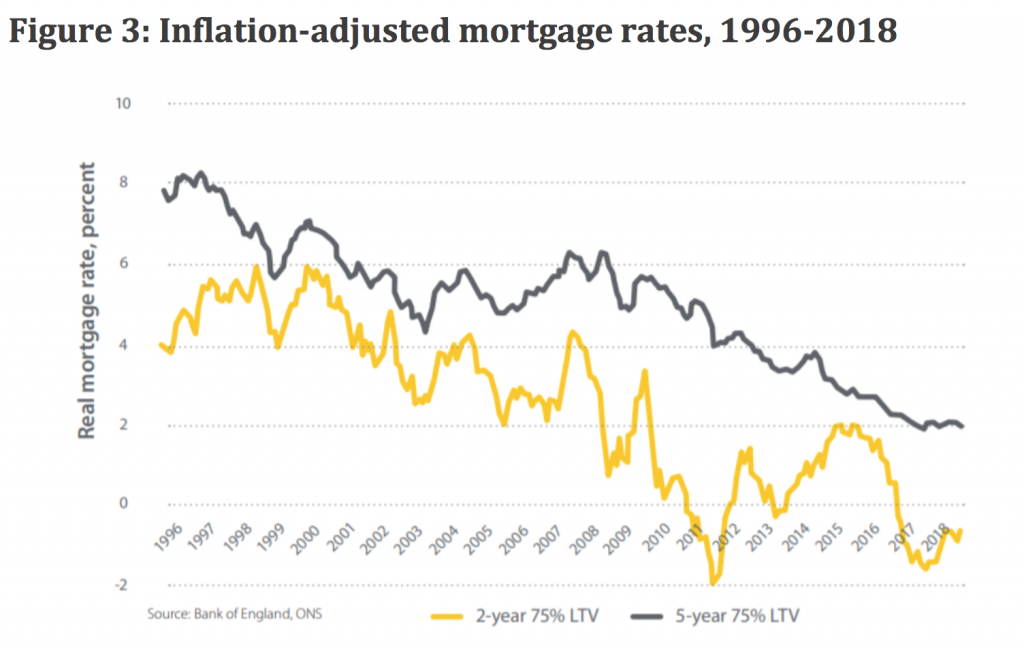

Since the late 1990s, mortgage rates have tumbled, with inflation-adjusted interest rates on five-year fixed-rate mortgages, for example, falling from 8% to around 2% today (see Fig. 3). Since mortgage interest rates tend to be the dominant element of the cost of capital for home owners, this change can be expected to precipitate a substantial increase in house prices of a similar magnitude to the 160% increase seen since 1996.

Note: LTV stands for loan-to-value.

Note: LTV stands for loan-to-value.

How much would 300,000 net additions per year improve affordability?

The growth in house prices in the UK over the past 23 years does not appear to have been the result of inadequate supply. But could greater supply nonetheless be the solution? Hitting the government’s target of 300,000 houses per year would certainly put more downward pressure on prices and rents. But the available academic evidence suggests that no plausible rate of supply would significantly reverse the price growth of the past two decades. Multiple modelling exercises, for the UK and elsewhere, find that a 1% increase in the stock of houses tends to lead to a decline in rents and prices of between 1.5% and 2%, all else equal.

This implies that even building 300,000 houses per year in England would only cut house prices by something in the order of 10% over the course of 20 years. This is an order of magnitude smaller than the price rises of recent decades. If we are to create more affordable houses to buy and rent, the solutions lie elsewhere.

The collapse of home ownership

High house prices are often seen as the cause of the collapse in home ownership across the UK. However a closer look at the data suggests that the mortgage market is a more important factor.

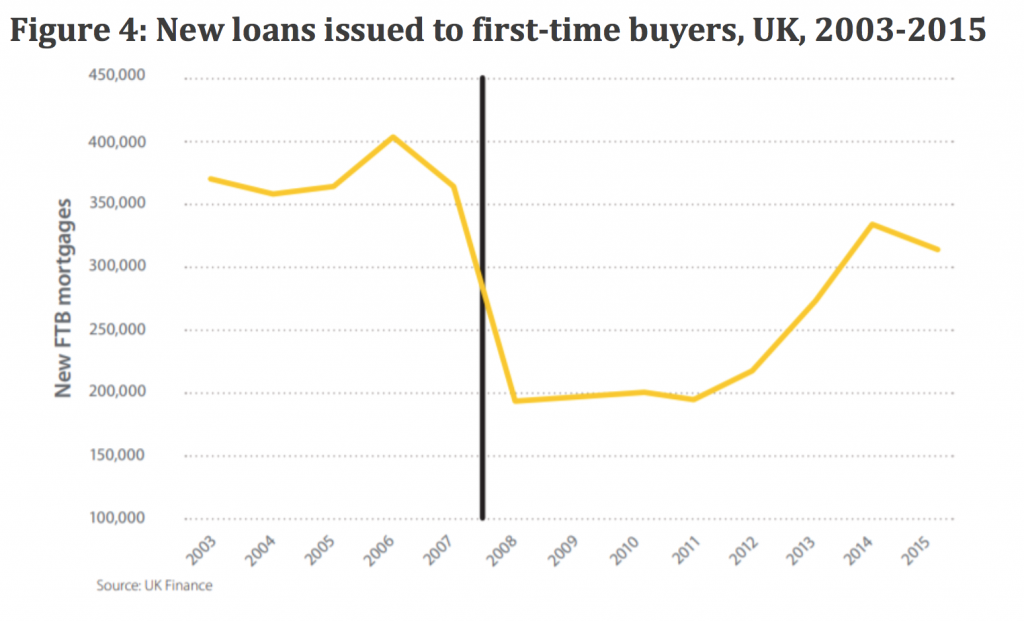

In England, home ownership peaked at 70.5% in 2003 but collapsed quickly from 69.1% in 2007 to 63.1% by 2016 – a period that saw quite sharp price falls across much of the country. The dominant cause of the collapse was the abrupt slowdown in mortgage lending to first-time buyers, which almost halved between 2007 and 2008, and did not recover until around 2016 (see Fig. 4). Had new first-time buyer mortgage issuance persisted at its pre-crisis rate, home ownership would not have fallen in the subsequent years.

Consequently, there is little reason to believe that supplying an additional 300,000 houses per year would raise home ownership. This is both because its impact on prices would be limited, and because ownership rates are much less sensitive to prices than they are to mortgage availability.

Policy implications

This analysis carries several important implications for the direction of housing policy in the 2020s.

- Plans to boost housing supply significantly above their current rates will not solve problems of high house prices or low home ownership.

- Growing housing affordability problems for young people in the private rented sector, rather than being the result of inadequate supply, appear to be due to a combination of slow wage growth, erosion of the social housing stock, and housing benefit cuts. Tackling these problems directly would be a far more potent (and less economically costly) way to improve affordability than boosting market supply.

- House prices are vulnerable to an end to the era of low interest rates and a reversal of overseas investment flows, with potentially serious political consequences. This should raise questions for policymakers about whether and how to insulate households from asset price volatility in future.

- If financial stability in the mortgage market is to remain a policy priority, raising the home ownership rate will require further fiscal intervention either to subsidise first-time buyers or to reduce financial incentives for landlords.

_______________

Note: you can read the full report on which the above draws here.

Ian Mulheirn (@ianmulheirn) is the Executive Director and Chief Economist  of Renewing the Centre at the Tony Blair Institute. He was previously Director of Consulting at Oxford Economics, a global economic consulting company, and Director of the Social Market Foundation.

of Renewing the Centre at the Tony Blair Institute. He was previously Director of Consulting at Oxford Economics, a global economic consulting company, and Director of the Social Market Foundation.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Most of your article depends on the 147k household showing less people want to buy (assuming it doesn’t include rentals)

What if you got your cause/effect wrong way round? There are fewer households because housing prices are too high

UK population has grown by over 400k a year where are they going to live?

You talk about “the collapse in home ownership” but how does the UK level of ownership compare with other similar countries? Is a high level of home ownership necessarily a”good thing” in itself? Are we teaching young people to feel inadequate in some way if they do not own a home? Are we stigmatising those who rent? Are not more important statistics the levels of homelessness and the the numbers of people living in poor quality housing?