Since the referendum, UK inflation has risen faster than that of the Eurozone. Price rises have varied across sectors, but Josh De Lyon, Swati Dhingra, and Stephen Machin show that the rise in the growth rate of food prices has been particularly pronounced. As a result, real wage growth in the UK has again turned negative.

Since the referendum, UK inflation has risen faster than that of the Eurozone. Price rises have varied across sectors, but Josh De Lyon, Swati Dhingra, and Stephen Machin show that the rise in the growth rate of food prices has been particularly pronounced. As a result, real wage growth in the UK has again turned negative.

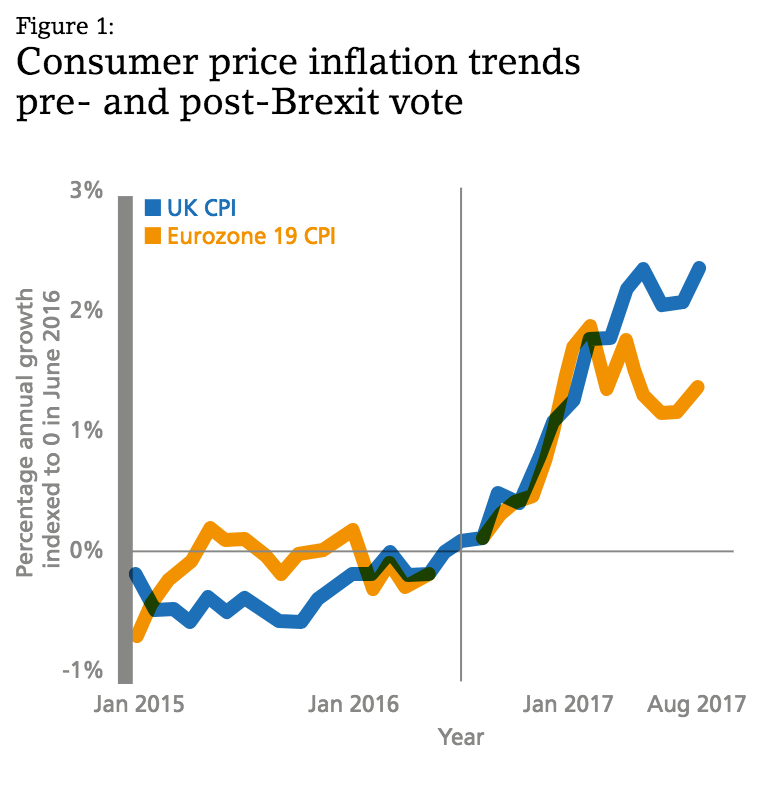

The pattern of significantly higher price inflation is shown in Figure 1. This plots the annual consumer price index (CPI) before and after the Brexit vote, comparing the UK with what has happened in the 19 Eurozone countries. To a large extent, the CPI growth rates of both the UK and Eurozone move together, with both being driven by worldwide commodity prices.

The index is a cumulated annual index and so only shows the full effect of the referendum from May 2017, when it is no longer diluted by pre-referendum data. Taking this into account, the spike observed shortly after the referendum is significant. It is likely to have been driven by the devaluation of sterling, which occurred immediately after the referendum result.

The index is a cumulated annual index and so only shows the full effect of the referendum from May 2017, when it is no longer diluted by pre-referendum data. Taking this into account, the spike observed shortly after the referendum is significant. It is likely to have been driven by the devaluation of sterling, which occurred immediately after the referendum result.

The full effect is indicated by the divergence of CPI annual growth rates between the UK and the Eurozone a year after the referendum. This divergence in consumer price inflation partly reverses the convergence in price changes that occurred in the single market, when price dispersion of tradable goods started to converge to levels seen across US cities by the mid-1990s (Rogers, 2001).

For certain commodity groups, the increase in the CPI growth rate has been more pronounced. Figure 2 presents the annual growth rate of CPI where the sample of goods and services is restricted to food. There is a distinct and substantial rise in the rate of CPI food inflation for the UK relative to the Eurozone.

The divergence that immediately followed the referendum is quite a bit larger than that observed for all goods in Figure 1, and becomes larger when amplified over time. This has important implications for how the vote has affected the purchasing power of different income groups. Low-income households spend a higher proportion of their income on food than rich households.

The divergence that immediately followed the referendum is quite a bit larger than that observed for all goods in Figure 1, and becomes larger when amplified over time. This has important implications for how the vote has affected the purchasing power of different income groups. Low-income households spend a higher proportion of their income on food than rich households.

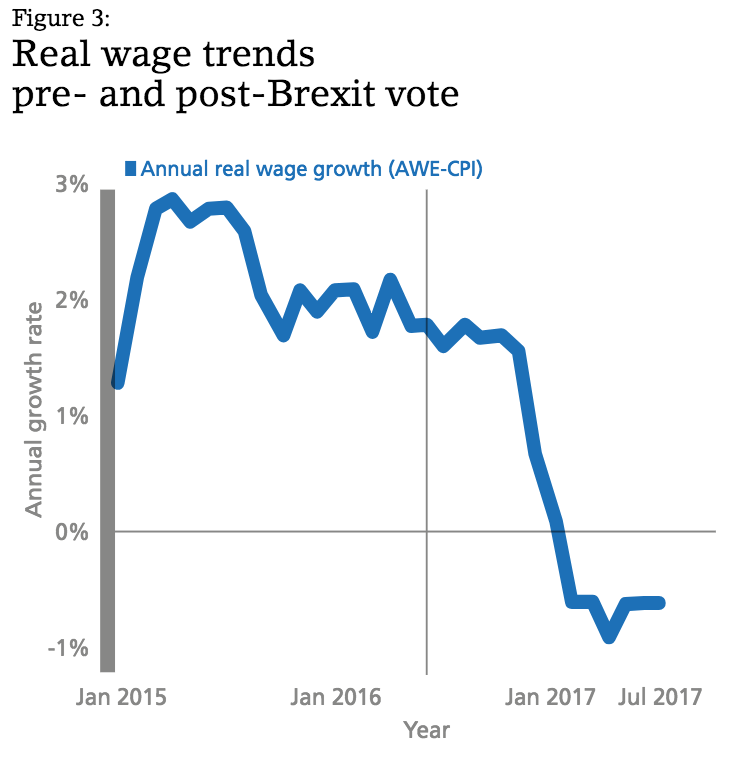

The UK experienced several years of real wage falls following the financial crisis of 2007/08, but in the period before the referendum, real wage growth in the UK had become positive (see here; and here). This arose because of very low inflation, not because of any strength in nominal wage growth (which seems to have become stuck at a norm of 2% per year since the start of the decade).

But the increase in prices following the Brexit vote coupled with no significant rise in nominal wages has again caused real wage growth to become negative. This is shown in Figure 3, which indicates that the real wages squeeze is back because of the post-referendum price increases.

By the end of our data period, the price increases following the referendum have now fully appeared in the annual index. It seems that the Brexit vote has caused a one-off rise in prices, and that the annual growth rate of prices will begin to fall out of the index once it no longer includes the months that immediately followed the referendum.

Overall, this research points to a significant rise in prices occurring after the EU referendum. Future work that builds on these initial findings will quantify the role of the devaluation of sterling by focusing closely on price changes for imported goods and services.

_______

This post is based on the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance report Brexit: the impact on prices. It was originally posted on LSE Brexit.

Josh De Lyon is a research assistant in CEP’s trade programme.

Josh De Lyon is a research assistant in CEP’s trade programme.

Swati Dhingra is Assistant Professor of Economics at LSE and a research associate in CEP’s trade programme.

Swati Dhingra is Assistant Professor of Economics at LSE and a research associate in CEP’s trade programme.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at LSE and Director of CEP.

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at LSE and Director of CEP.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: CC0 Public Domain.

I’m puzzled why the LSE makes no reference to the pre-referendum consensus, which included the IMF, that Sterling was between 5%-15% overvalued, on a trade-weighted basis. Other analysts (Ashoka Mody of Princeton) put the figure as high as 25%.

This would indicate that far from Britain’s imports being “cheap”, they on the contrary reflected the hobbling of the UK’s export potential, and a huge advantage enjoyed by foreign suppliers in the UK market.

Does the LSE defy conventional wisdom and see this situation as somehow optimal? Its Brexit-related coverage would seem to suggest so.

So the quicker we leave EU and no longer apply CET especially to imports of food the better off the UK consumer will be.

Wage growth can improve when we stop Free Movement of the Unemployed from the Southern and Eastern members of the EU which has had a calamitous effect not only on the distortion of the UK labour market against the British low pay sectors but also taken skilled people from those countries.

You clearly have never head of tariffs then… good grief.

You clearly don’t realise that tariffs are applied on imports by the EU not the UK – we do not have to apply the EU Customs Union Common External Tariff to goods . Especailly as this goes directly to Brussels.

Or perhaps you really do not understand how the EU protects its so called Single Market from outside competition and beggars Cash Crop developing nations by crippling their ability to process these into consumer products by levying enormous CET on their import? That for example the World value of raw coffee is less than the processed coffee products of Germany, at a huge hike.